At a time when race, religion, colour, caste, gender and nationality are so important in defining a person’s identity, the life of Freda Bedi, who broke glass ceilings and crossed boundaries at every step, stands out. Freda was a woman of many parts — mother, political activist, writer, social worker and eventually Buddhist nun — and she was a pioneer in all of them.

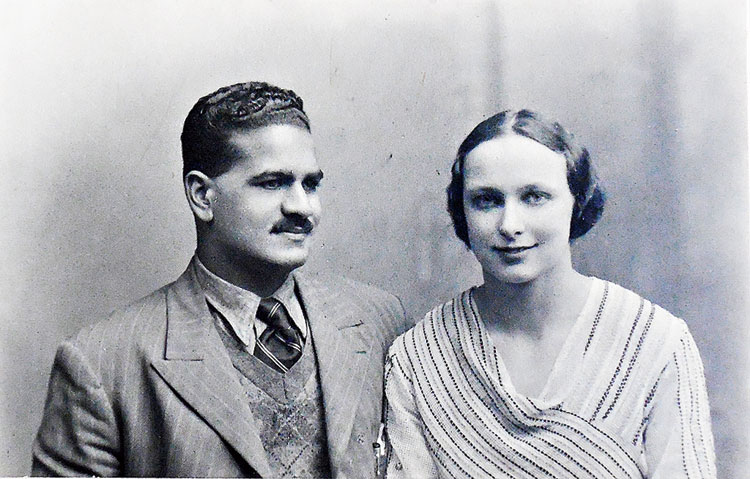

The quintessential English beauty — blue-eyed and blonde-haired — became more Indian than the best of us, wearing only saris and salwar suits from the moment she married her Punjabi husband, Baba Pyare Lal Bedi, at a registry office in Oxford in 1933. The marriage itself broke the barriers of class and colour that existed at the time. Elite, educated English ladies did not marry Indian men in those days. It was frowned upon and left only to lowly working class women to succumb to the charms of the brown-skinned man.

Freda did not believe in such racism and became the first English woman who chose to marry an Indian fellow student while they were both at Oxford University; that stirred quite a social scandal. Courageous and daring, Freda did not care for convention and went against her family to marry Bedi. In Freda’s words, the couple was “two students in love, refusing to recognise the barriers of race and colour, dissolving their religious differences into a belief in a common good, united in their love for justice and freedom”.

A revolutionary both in spirit and deed, Freda moved to India with her husband and young baby and defying the norms of nationalism, she joined the freedom struggle along with Bedi. Despite being a daughter of the British Raj, Freda fought against imperialism and even served a stint in Lahore jail for being one of Mahatma Gandhi’s satyagrahis.

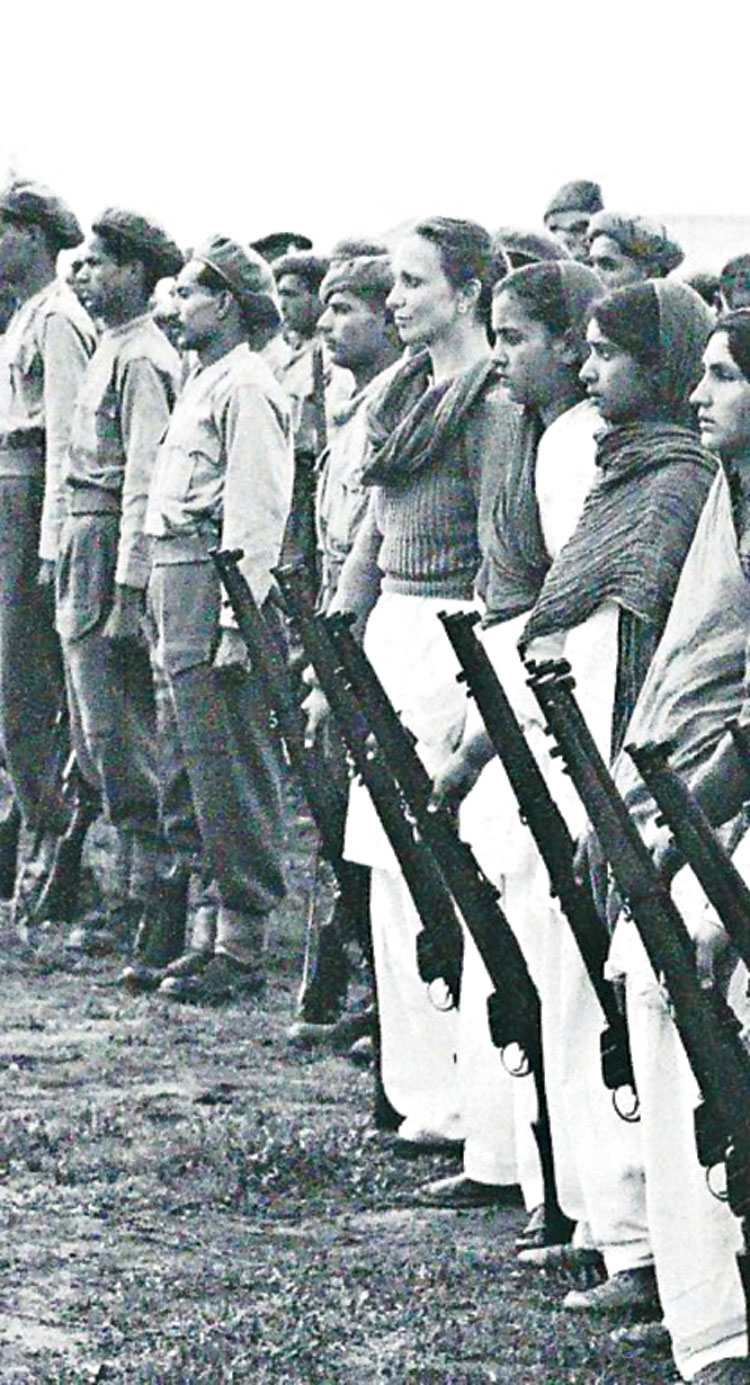

By Partition, Freda and her family had moved to Kashmir where she and Bedi worked closely with Sheikh Abdullah. Freda enrolled in a Left-wing women’s armed militia and ran messages to Sheikh Abdullah’s supporters disguised in a burqa.

“Freda Bedi delighted in confounding accepted definitions of identity. She could not be easily categorised and saw no reason why she should be,” writes Andrew Whitehead, a former BBC India correspondent in the just released biography, The Lives of Freda: The Political, Spiritual and Personal Journeys of Freda Bedi.

As part of Kashmir’s militia Source: The Bedi Family

Another boundary Freda crossed effortlessly was that of religion. Born in 1911 into a middle-class Christian family in the provincial town of Derby in central England, Freda Houlston was a church-going youngster. However, when she went to St. Hugh’s College, Oxford, in 1929, she left Christianity behind and became an active Leftist. Her sense of justice and equity was so strong, she saw that as her religion.

More than two decades later, Freda encountered Buddhism on a UN assignment in Burma [now Myanmar] and her spiritual interest was piqued. She studied meditation with Burmese masters.

In 1959, as the Dalai Lama and Tibetans sought refuge in India, Freda persuaded the then prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, to give her a role coordinating efforts to help the refugees. In 1961, Freda established the Young Lamas’ Home School in Delhi and it was as she helped the Tibetans adapt to exile that she realised that she had found her spiritual home in Buddhism.

With her mother and brother Source: The Bedi Family

At a time when it was rare for Westerners to flirt with eastern religions, Freda became a novice Buddhist nun. In 1966, she was ordained as Buddhist nun at the Rumtek monastery in Sikkim by the 16th Karmapa Lama, definitely becoming the first Western woman, and possibly the first woman ever to receive this higher level of initiation in the Tibetan tradition. As Sister Palmo with her steely blue eyes, shaven head and maroon robes, Freda had come a long way from her provincial English, Christian roots. It was this avatar of Freda that got her the most fame. In 1972, Sister Palmo became a fully ordained bhiksuni — another glass ceiling broken!

Freda died in Delhi in 1977 having lived two-thirds of her life in India, submerged in the causes and culture of her adopted country even taking on an Indian passport. “When her friend Indira Gandhi gave her an award for services to India as a foreigner, she was ‘very upset’. After spending her life challenging crude labels of identity, she was still seen as an outsider because of the colour of her skin,” said Whitehead.

According to Whitehead, Freda demanded a biography at this time because of the way she lived her life. “She constantly crossed borders — not simply national borders, but also those less tangible lines which divide on the basis of faith, ethnicity and sex. In Freda’s lifetime, these lines were more deeply etched than they are today — but they still remain deep social and political fault lines, and for those who wish to bridge them, Freda’s life is inspiring,” he says.