Dionne Warwick refuses to stay put. At 82, the fivetime Grammy-winning artiste is making stops in Hawaii and Vancouver on her One Last Time tour — she won’t say whether it’s truly her last — tweeting (or “twoting,” as she calls it) to her more than half a million followers, and making appearances on S.N.L. and on movie soundtracks like Jordan Peele’s Nope. When she retires, she said, she’ll move to Brazil.

“I will be laying in Bahia, where I want to spend the rest of my life, enjoying the sunshine, the music, the people and me,” Warwick said.

In the meantime, Warwick’s next venture is onscreen. In the documentary Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over, she, along with well-known interviewees like Bill Clinton, Stevie Wonder and Alicia Keys, discusses her life and her 60-plus-year music career.

Directed by Dave Wooley and David Heilbroner, the film details moments from Warwick’s childhood, including singing in her grandfather’s church in Newark and chronicles chart-topping hits like Walk On By and I’ll Never Fall in Love Again, which were made with the producing and songwriting duo Burt Bacharach and Hal David. Those songs challenged the racial barrier between rhythm and blues and pop. (In 1968, Warwick became the first African American woman to win a Grammy in the pop music category.)

As Warwick munched on cheese and crackers at the CNN offices in Manhattan, she talked about being a spokeswoman for the Psychic Friends Network, her motivation to support AIDS research and how she met Snoop Dogg and Chance the Rapper. Following are edited excerpts from the conversation.

The documentary is titled Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. What inspired the name?

Don’t Make Me Over was my first recording, my very first one, and the genesis of that was something I said to both Burt and Hal. I was promised a certain song, Make It Easy on Yourself, and they gave that song to Jerry Butler. I was on my way down to do a session with them and when I walked into the studio, I had to let them both know that I was not very happy about them giving my song away, first of all. That was something that they could never, ever do. Don’t even try to change me or make me over. So David put pen to paper.

The documentary discusses your upbringing. What was it like growing up in East Orange?

It was virtually the United Nations. We had every race, colour, creed and religion on our street. We were friends, we walked to school together, I had dinner at their homes, they had dinner at my home. We played at the playground together. We were just kids and hung out with friends.

How were you able to create music that appealed to all audiences during the 1950s and 1960s, when rhythm and blues and pop music was racially classified?

The fortunate thing is I could not be categorised. That was a joy. I look at — I still do this very day — and I continue to preach the fact that music is music.

I don’t look at myself as the person that threw the door open. I just paved the way to let people know, “Yeah, Gladys Knight deserved a Grammy, yeah, the Temptations deserved the Grammy, yeah, Diana Ross deserved it.” Of course! We’re singing music that all of you are listening to, so why are you going to put us in a little box? I ain’t going.

By donating all the proceeds of the chart-topping song That’s What Friends Are For, you’ve helped raise millions for AIDS research. What led you to get involved with the cause and how does it feel to leave such a lasting impact?

We were losing performers, we were losing dancers, we were losing hair people, we were losing wardrobe people, cameramen, lighting people.

I’ve lost two people in my group of people around me: my hairdresser and my valet both contracted AIDS. So, now, that’s too close. Let me find out what this is about. And I proceeded to get involved with WHO, World Health Organisation, and we went to all the health departments in different countries to get a handle on not only what they were doing, but why they were not acknowledging that it’s happening in the country. I was able to help them bring their heads out of the sand and face reality.

In the ’90s, you got involved in the Psychic Friends Network. What encouraged that decision?

It was during a period of time when my recordings were not being played on radio as much. It was a way to earn a very, very comfortable living. It paid very well — had to keep my lights on, too. So that’s how that all began.

I can’t nor would I ever think about taking it seriously. And anybody that does, you have to look at them with a jaundiced eye.

You felt very strongly about gangster rap, and set up an early meeting with Snoop Dogg, Suge Knight and others to encourage them to reconsider their lyrics. How did that conversation go?

I called a meeting with them, and I gave them a time to be at my home. I told them not one minute before and not one minute after 7am, I want that doorbell to ring. And it did. We sat and talked for quite a few hours. I told them, “You think I’m part of the problem? Make me part of the solution. Tell me what it is.” I said, “I have no problem with you saying whatever you’re feeling; however, there’s a way to say it.”

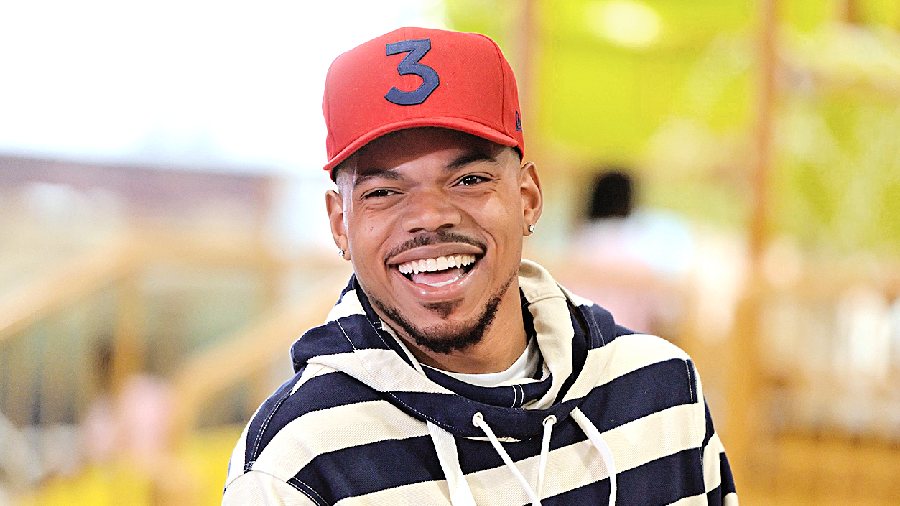

Chance the Rapper

Have you reached out to any other rap artistes recently?

Chance the Rapper, that was a funny thing as well. Why would you have to put “rapper” in your name when we all know you rap? Duh.'

He was more surprised that I even knew who he was, and as a result we’ve become friends. He has my phone number, I have his and we do talk. We recorded together, a wonderful song and not one curse word — a very, very positive message. So it’s not like they can’t do it, and if they need to be led a little bit, hey, that must be my job to do.

Amid the pandemic, you rose to Twitter royalty. What’s it like to be crowned the queen of Twitter?

They gave me the title. I didn’t take it. I didn’t give it to myself. They all decided I was the queen of Twitter. So yeah, OK, I’ll be your queen of Twitter. In fact, I started a new way of saying Twitter, I call it twoting.

Twoting? Why twoting?

I didn’t want to say “tweet.”

The New York Times News Service