The city has almost forgotten a dreaded word: load-shedding. But it was such a part of its life once that some grew up thinking it was a Bengali word. And that power cuts, what the word had come to mean, were inevitable and could strike at any moment, any place, for the longest hours.

The original meaning and purpose of load-shedding, which was controlled power cuts that were meant to prevent the entire system from collapsing, was obscured by the arbitrariness with which it occurred.

But the city has also almost forgotten that it had staged a spectacular protest for power against the powers-that-be when it finally got fed up. In the process it also earned some respect for its middle classes, which had by then acquired the reputation of being indifferent and averse to fighting the good fight.

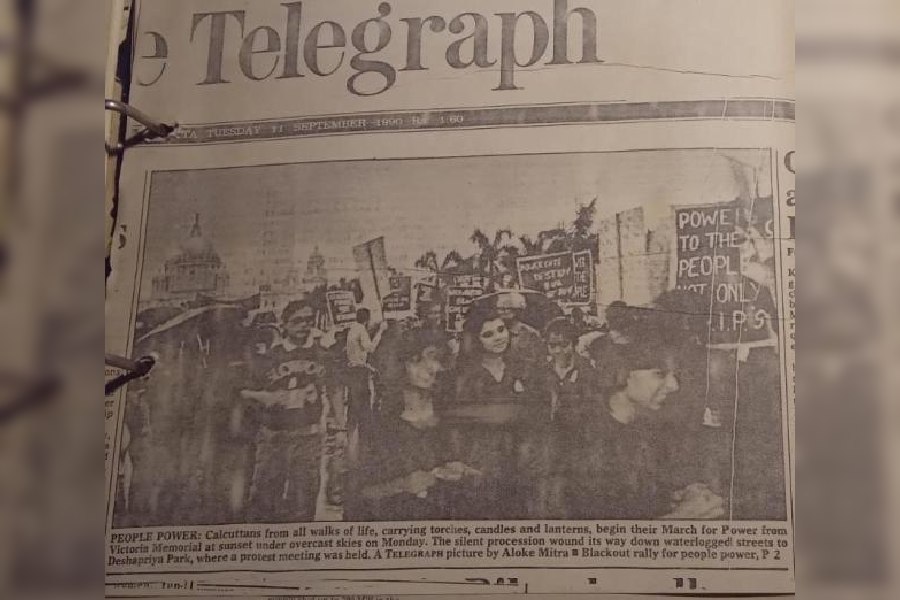

On September 10, 1990, about 3,000 Kolkatans had marched from the Victoria Memorial to Deshapriya Park, setting out at sunset and wading through waterlogged streets. The idea was to catch the eye of Writer’s Buildings, often unseeing. Another challenge had been how to get the maximum number of Kolkatans to join.

The situation was desperate by then. The city had been suffering load-shedding for hours, sometimes entire nights, for more than a decade. People would get trapped in lifts, surgeons would stop mid-surgery, students preparing for exams would hunt for candles and summer evenings would be unbearable, AC being an absolute luxury item then. A few could afford generators, which added more noise and fumes to the city’s pollution, and a few others used inverters, which had limited capacity.

The state Left Front government did not seem very concerned. Ironically the chief minister then was Jyoti Basu, whose first name meant light.

“In a debate in the Assembly on August 24, 1990, Prabir Sengupta, power minister of the state then, denied responsibility for the dismal power situation and blamed the former Congress government at the Centre for creating hurdles and stopping the growth of Bengal,” reminded Bonani Kakkar of PUBLIC, a voluntary citizen action group to give to Kolkata a better living environment, which had just been formed then.

Kolkata depended on three sources for electricity then — the Durgapur plant, Damodar Valley Corporation and central agencies. But even on a Sunday in August 1990, a shortfall of 100MW hit the city and caused eight hours of power cuts, as a report in this newspaper on August 11, 1990, said.

Other than the Centre, former or otherwise, the state government also blamed poor quality or wet coal, erratic transmission frequency and breakdowns in the ageing generating stations.

A group of citizens, among them members of PUBLIC, got together and proposed a march. It was meticulously — and joyously — planned. Eminent advertising professional Ram Ray led the design. The march was branded, called “March for Power”; it had a logo (see picture); and it came up with colourful slogans, glowing wittily on black background. One in English said: “Kolaghat Bandel/ Schools for scandal”! Kolaghat and Bandel were two poorly performing power stations. Another in Bengali quoted Tagore, accusing the powers of putting out the lights.

But the procession was silent and marched in a single file, so as not to obstruct

traffic.

The route maps from the Victoria Memorial to Deshapriya Park were publicised widely, because of subsidised rates from media houses. People were urged to join in anywhere. Participants were requested to wear black or dark clothes and carry oil lamps. “The march was led by a black jeep, naturally,” said Kakkar.

“About 3,000 people joined at various points, despite the torrential rain,” she added. They included the middle classes and the “PLUs”.

“Women in expensive saris walked alongside mothers carrying babies, undeterred by the downpour that struck halfway through the march,” Kakkar said. Some women blew conch-shells from their Sarat Bose Road balconies.

The next day newspapers reported the event, many of them on the front page. “Even Ganashakti, the CPM mouthpiece, took a swipe at our ‘middleclass-ness’ by commenting that now Kolkatans sipping from tetrapacks could be seen marching on the streets,” laughed Kakkar.

Though the marchers did not hear from the Writers’ directly, the event was too large a one to miss. Three months later, an open letter was addressed to the chief minister. It was signed by several prominent Kolkatans, such as film director Mrinal Sen, actor Aparna Sen, writers Sunil Gangopadhyay and Nabaneeta Dev Sen, artists Paritosh Sen, Shanu Lahiri and Ganesh Pyne, educationists John Mason and Gauranga Chattopadhyay, and from the corporate world, Ram Ray, Nari Narayan, Subhas Ghosal and Sukhendu Ray.

The power situation in the city improved slowly. “Cynics claim that Kolkata’s comfortable power situation today is because industry fled. That’s a matter of data — what we do see is that power consumption has increased hugely, as seen in malls, highrises, and retail outlets. We are happy that Kolkata no longer needs to march,” said Kakkar.

But not all of Bengal is Kolkata and not all of Bengal is free of power cuts. And darkness is a useful metaphor — we need light in so many areas of our public life.