Samar Bagchi, who calls himself a young man of 90, speaks excitedly about a trip to a village in Bankura district about a month ago. He was visiting Soumya Sengupta, a primary school teacher, in Radhanagar, Bishnupur. During the pandemic Sengupta has been making videos for thousands of district students on several subjects and broadcasting them on a cable TV channel.

“His mathematics lessons are brilliant. Mathematics is an abstraction of the real world,” says Bagchi.

Teaching it is a challenge, in the classroom, remotely, even more so. Teaching in itself is a challenge, given the limited resources here, especially for science. “There are very few laboratories in schools in the state. Science streams are shutting down. Teachers have lost the desire to teach,” says Bagchi.

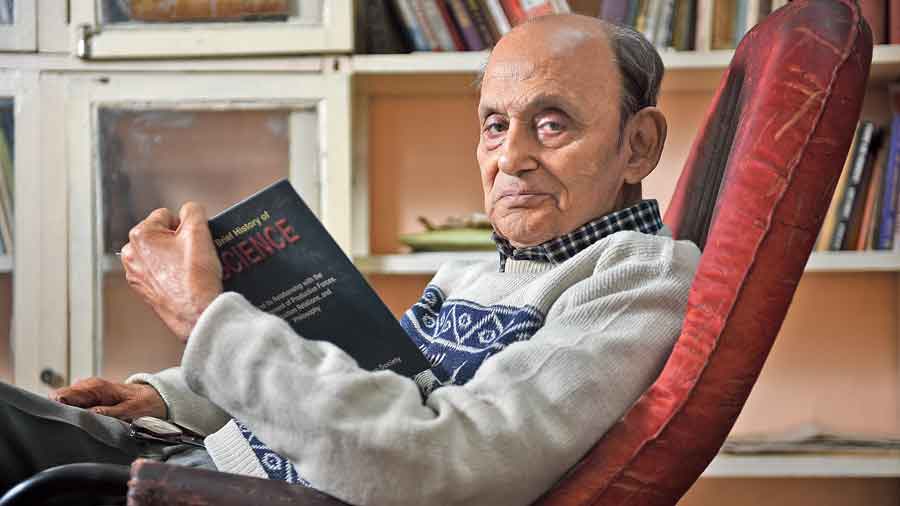

Though never technically a teacher himself, Bagchi, former director of Birla Industrial and Technological Museum (BITM), Kolkata, took up this challenge decades ago and has been working tirelessly on it. He does science teaching, principally for teachers, still visiting schools when required. He is a restless man who will not allow age or ill health to come in his way (and will also speak with humour about his relentlessness). To demonstrate how science can be taught practically in the classroom, he uses experiments with “no-cost, low-cost materials”, a slogan he proudly takes credit for.

The science that he envisages is gentle, rooted in an old humanism that today sounds radical, when not discarded as irrelevant. He takes his inspiration from Tagore, Gandhi and Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray — and also Marxism.

After a long and distinguished career devoted to popularising science at BITM, an organisation under National Council of Science Museums, Bagchi took up science teaching actively on his retirement in 1991.

“I have conducted 350 to 360 workshops for science teachers throughout the country from Kashmir to Kerala, from Gujarat to Andaman and Nicobar Islands,” he says.

He would often start a workshop by testing the teachers. He would give them two strips, one iron and the other magnet, and ask them to say which is which in 3 seconds. “Most could not answer correctly. But all one has to know is that the centre of the magnet does not attract,” he says.

He had to use the wheelchair at Bishnupur railway station to get into the car for Radhanagar. He stayed with Sengupta for two days, recording six to seven lessons every day, from 8.30am to 8.30pm, with a lunch break in between. Bagchi mainly demonstrates physics experiments, from Archimedes’ principle to Bernoulli’s.

In the Eighties, he was a well-known face on television with Partha Ghosh as a host of Quest, the interactive science quiz programme from BITM telecast on Doordarshan nationally.

“Science is doing,” says Bagchi, who also describes himself as a social activist and environmentalist. “That is what both Acharya Prafulla Chandra and Tagore had said in their writings.”

We are sitting in Bagchi’s drawing room in a quiet and friendly Tollygunge housing complex. The room is plain but soothing and has arresting prints of Chagall and Picasso on the walls.

He was born in 1932 in Purnia in Bihar and grew up in a large family.

“The Durga puja there was sheer joy. We would get two shirts and two pairs of pants.” This is unthinkable today, he laughs. After his father’s early death, he and his six siblings were raised by his father’s brothers in Kolkata. He says he and siblings owe everything to their uncles.

He studied B.Sc at Scottish Church College in north Kolkata and went on to Indian School of Mines in Dhanbad, where he obtained a first-class in mining engineering. He worked in the mines for some time but after a spine problem, decided to return to Kolkata, where his heart belonged.

The city had opened his mind. It had introduced him to reading. He had been inspired by a Communist friend. “The first book that I had purchased from Beadon Street was Christopher Caudwell’s Illusion and Reality, a book on Marxian aesthetics. Marxism allowed me to enter into the world of books, which (André) Malraux calls the museum without walls,” says Bagchi. He joined BITM as curator, mining and metallurgy, in 1962. After Saroj Ghosh became director- general at National Council of Science Museums, Bagchi became the director there. He calls Ghosh “a giant personality”. Bagchi was also in charge of four more museums in eastern India.

He is particularly proud of the exhibitions at BITM created during his tenure. He was part of a two-year exhibition in the US on 5,000 years of Indian science, to which he added sections on the contribution of Indian music and linguistics to science. Indian classical music has sustained Bagchi and vocalist Aamir Khan and sitarist Nikhil Banerjee being favourites.

In this context, he reads to me a beautiful poem by Arun Mitra, who was a friend, on the birth of the sound in the poet’s mind. Though a “hardcore atheist”, Bagchi reads spiritual leaders, “when they relate to the lives of people”.

He is the chairperson of Khelaghar and two other schools. Many girls from the Santhal community are educated at the Badu campus of Khelaghar in Madhyamgram. Bagchi is a close associate of activist Medha Patkar.

During the pandemic, he has conducted three webinars on the “alternative paradigms of development in Tagore and Gandhi”.

“Tagore and Gandhi had wanted a different society, a new kind of India,” says Bagchi. “They had both warned about following the trajectory of Western industrialisation. But the Western idea of progress has entered our minds. Tagore had pointed this as early as 1905 in an essay on ‘the lifestyle trap’, and later, more famously, in the essay Sabhytar Sankat (The Crisis of Civilisation), 1941. The hegemonisation of the mind is complete,” says Bagchi.

“Science cannot be tied down to consumerism and capital. Science has to work in harmony with nature.” In the last 10 years in India jobs generated can be counted in lakhs, he says, when the population of the country is 140 crore. “Only inequalities are increasing. With AI and robotics there will even fewer jobs.”

He talks about societies with a higher culture built on knowledge and science, about which history can provide a clue. He refers to the Islamic Renaissance of the 9th century and the exchanges of ideas and culture generated then. “The Indian scholar Kanka had gone to the court of Al-Mansur with Brahmasphutasiddhanta, a mathematical treatise,” says Bagchi. This he learnt from Acharya Prafulla Chandra’s writings on the contribution of Islamic civilisations to science, including algebra (from Arabic al-jabr).

He feels that in the past few years, Bengal has made considerable social progress, especially when one looks at indicators like health and nutrition, but is worried about an enterprise like the coal mining project at Deucha-Panchami in Birbhum. He feels the displacement of the tribals cannot be compensated for by any monetary package.

“But it’s a sin to lose faith in humanity. Manusher prati biswas harano paap, Tagore had said at the end of Sabhyatar Sankat, the 1941 essay, aged 80, in the year of his death.”