May 18, 1985, was as ordinary a day for most of the world as any other day. Except for a dusty, old town nestled around 160km from Kolkata, with a preponderance of red laterite soil and a 125-year-old railway station, its only claim to fame a university established by Rabindranath Tagore.

That was the day Bolpur, in West Bengal’s Birbhum district, elected a new MP — Somnath Chatterjee — to represent the constituency in the Lok Sabha, the lower House of India’s Parliament.

Chatterjee’s push for a model of development, heavily reliant on brick and mortar, would set the stage for a confrontation that eventually culminated in an announcement last Sunday that the foot soldiers of Santiniketan’s battle for preservation had been waiting for. On September 17, the World Heritage Committee recognised Santiniketan as a World Heritage Site, making it the 41st such site in India to be granted the status and, by extension, protection from any kind of construction, encroachment or intervention, not related to maintenance, in and around its vicinity.

A statement from UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee said Santiniketan was one of the most “avant-garde visions of an international educational and cultural institution” conceptualised at the beginning of the last century.

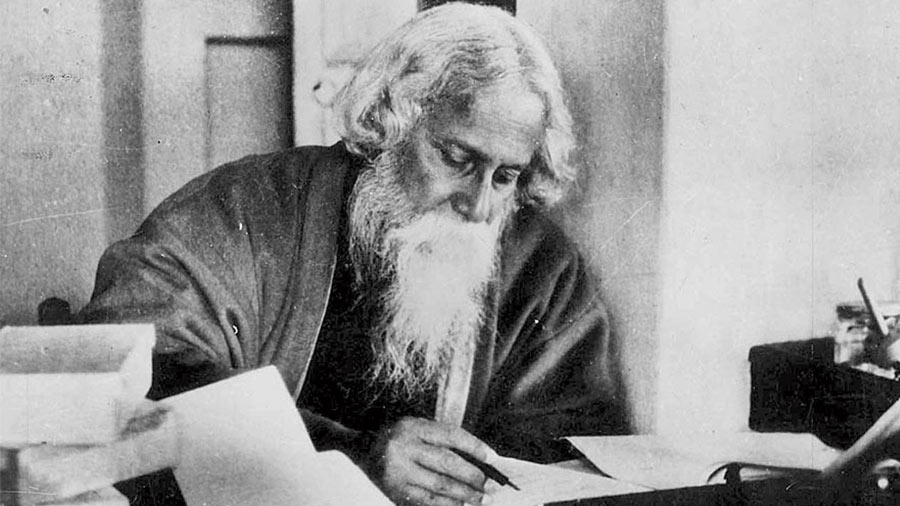

“The site stands testimonial to Rabindranath Tagore’s vision and philosophy of where ‘the world would form a single nest’ using a combination of various elements including education of children, nature loving environment, use of music, and arts for emotional development. The vision includes social work to help the local community, research on philosophy, cultures etc. and continues to maintain its distinctive authenticity and integrity through its living tradition. The integrity of the site has been maintained even with the change of ownership from the Tagore family to Visva-Bharati,” the statement added.

‘The site stands testimonial to Rabindranath Tagore’s vision and philosophy of where ‘the world would form a single nest’,’ a statement from UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee said TT Archives

For Partha Ghose, one of those at the forefront of a two-decade-long struggle to save Santiniketan from commercial exploitation, the wait is finally over. “This (World Heritage Site status) is possibly the only way to preserve Santiniketan,” Ghose, a physicist and trained musician with more than five decades of association with Santiniketan and Visva-Bharati, the university Tagore had founded over a hundred years ago in 1921, would tell My Kolkata, shortly after the September 17 recognition.

Sunday’s announcement came at Riyadh where the World Heritage Committee was meeting for its 45th session. A day later, on September 18, the heritage committee would also include the Hoysala-style temple complex in Karnataka in the list of heritage sites. The twin events came exactly 40 years after the caves at Ajanta and Ellora, the Agra Fort and the Taj Mahal became the first Indian entries in the coveted list in 1983.

Long story with many connecting dots

Nobody could have known back then in the summer of 1985 that Santiniketan, a hermitage established by Tagore’s father Debendranath Tagore, would ever require a heritage tag. But then, nobody could have foreseen the construction boom that followed the formation of the Sriniketan Santiniketan Development Authority (SSDA). That was in 1989, about four years after Bolpur had elected Chatterjee as its MP.

Chatterjee, who is no more now, chaired the Authority for nearly a decade and a half since its inception, a period that saw the sleepy, idyllic town transform into an urban hub with residential complexes, hotels and resorts. The barrister turned MP, a charismatic figure in political circles, had been quick to realise Bengal’s abiding fascination with anything to do with Tagore.

While talking to this writer in March 2009, Chatterjee, then Speaker of the outgoing Lok Sabha, had expressed his unhappiness with the way things were in Bolpur, a constituency he had represented uninterrupted since 1985. He called the town “one of the dirtiest” and said he was concerned about the impression that Bolpur made on first-time visitors and wanted things to be done in “a certain way”.

Somnath Chatterjee had been quick to realise Bengal’s abiding fascination with anything to do with Tagore TT Archives

But there were many who saw in the town’s construction boom not only a threat to its ambience and environment but also an attack on the very essence of Tagore’s philosophy and his vision of Visva-Bharati. Ghose, now 84, was one of them.

“I have an emotional attachment with Santiniketan. Jayga ta noshto hoye jachchhe (The place is being destroyed). It used to hurt,” Ghose says.

Ghose had joined Visva-Bharati as a physics teacher at Siksha Bhavana on October 28, 1968. “There weren’t so many houses then. Large parts still resembled the way Tagore had left it (in 1941, the year the Nobel laureate died). Going to the Khoai (a geographical formation made of laterite soil) for a picnic was part of the curriculum.”

Ghose would later be appointed secretary to the now defunct Visva-Bharati Music Board, which held a clergy-like grip on Tagore’s songs till the midnight of the new year of 2002, when the copyright on his works expired.

Sometime early this century, Ghose decided to do something about the town he deeply cared for. He approached novelist and social activist Mahasveta Devi and others to save Santiniketan and what remained of its surroundings. That led to heated exchanges during meetings with SSDA officials, signature campaigns, petitions in court and sit-in demonstrations. Environment activist Medha Patkar, too, would lend her support during a visit to the campus. “Somnath babu’s idea of development was different,” says Ghose. “He didn’t accept our views; we didn’t accept his.”

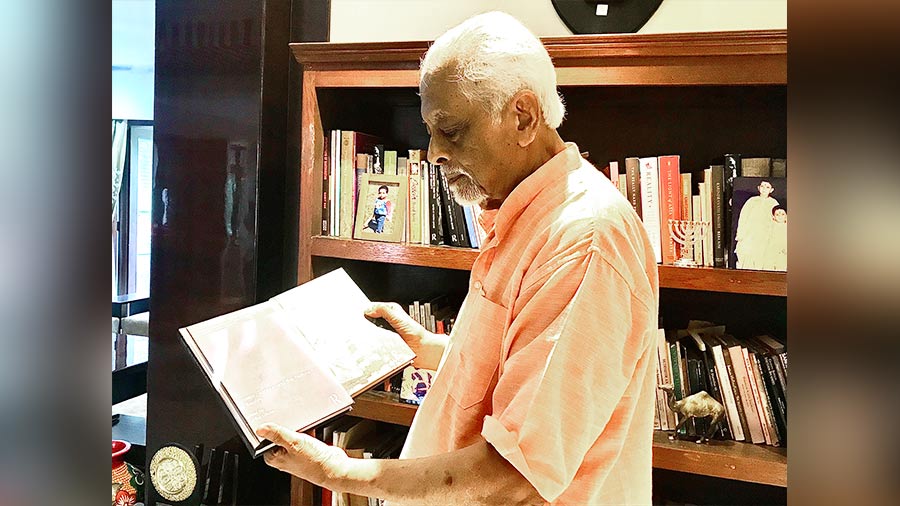

Partha Ghose at his Ballygunge Park Road home Arnab Ganguly

The showdown finally reached Calcutta High Court where the plaintiffs — those against any form of construction in Santiniketan and its vicinity — suffered a setback.

While dismissing their plea, a division bench observed that even if Tagore were alive it “cannot be disputed” that the continued increase of population in Santiniketan and building activities there would “slowly change the place almost beyond the recognition of the poet”.

The bench said there was no provision in the Visva-Bharati Act of 1951 that required Santiniketan to be made an exclusive spot forever, and that allowing the town to retain its original form would be impractical. So, it could be permitted to become a residential town or even an industrial hub, provided the growth was planned, systematic and in accordance with laws.

The battle then moved to the Supreme Court, which ruled in favour of the appellants. In a 2005 ruling, a two-judge bench said it was not being suggested that Santiniketan should remain as it was in 1921 but it could not be permitted to become a concrete jungle and an industrial hub. The land use and future planning of Santiniketan must be done in such a manner, the top court said, that the changes do not go beyond the recognition of the poet and the provisions of the 1951 Act.

On the ground the construction of a mega residential project was allowed to continue, though the SSDA was asked to adhere to the rules in future projects.

In 2006, Mahasveta Devi wrote to then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh that a high-ranking university official was even planning to start a tea garden in the Khoai. Santiniketan was still under threat.

The Khoai in Santiniketan Wikimedia Commons

Root of the trouble

Ghose thinks Visva-Bharati’s troubles can be traced back to May 1951 when the Indian Parliament passed the Visva-Bharati Act, turning it into a central university and imposing what he called a reign of bureaucracy. “That single move destroyed the soul of Visva-Bharati gradually and here we are today. Many objected to it, but Jawaharlal Nehru (independent India’s first Prime Minister) went ahead with the move. A conventional university cannot protect and preserve Tagore. Visva-Bharati was developed as a modern form of an ashram, a tapovan. A bureaucrat from Delhi cannot fathom that.”

Pandit Thakurdass Bhargava, a member of the Constituent Assembly and Lok Sabha member from present-day Haryana’s Hisar (then in Punjab), had warned about the Visva-Bharati bill’s possible impact during the debate on the legislation. “Yesterday, Maulana sahab (Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, the country’s first education minister) had said this is a strange university where students are taught under trees, where cement and steel have little to do. But in this bill I can only see cement and steel. That soul which resides in the university is invisible in the bill.”

Ghose says Tagore never wanted Visva-Bharati to be just another university. “But the Visva-Bharati Act did exactly that. I don't know why those in Visva-Bharati then had remained silent.”

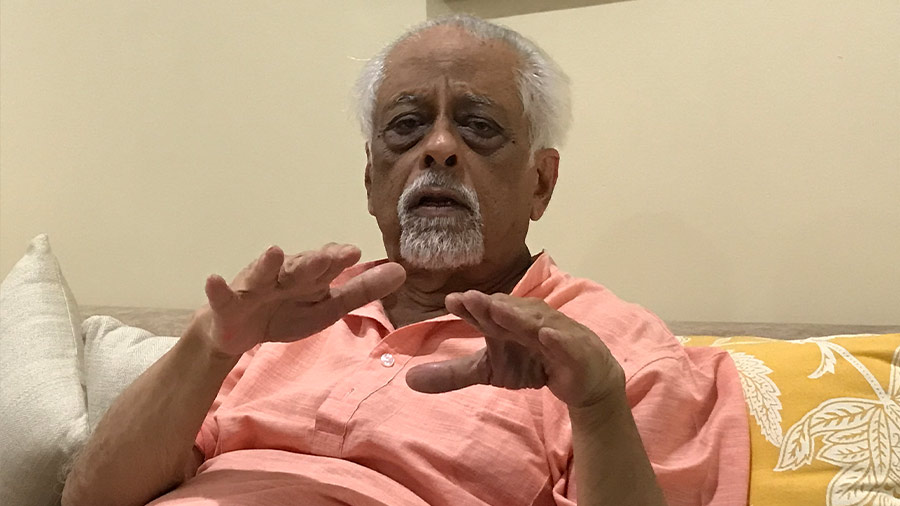

Ghose thinks Visva-Bharati’s troubles can be traced back to May 1951 when the Indian Parliament passed the Visva-Bharati Act, turning it into a central university and imposing what he called a reign of bureaucracy Arnab Ganguly

He also points a finger at Visva-Bharati’s internal decisions, citing as example the numerous boundary walls that have come up all over the campus, mostly over the last two decades. “Tagore never thought of boundary walls. They have even built a wall between Sangeet Bhavana and (the late teacher-singer) Santidev Ghosh’s house. That shed over Ramkinkar Baij’s Santhal Family sculpture is preposterous. Tagore would not have approved of it. There is no sensitivity these days. All everyone does is pay lip service to Tagore.”

Finding a solution

Around 2009, Ghose started looking for a solution that could have a lasting impact. “I knew the Taj Mahal was on the World Heritage list and there were restrictions imposed despite it being a major tourist destination. I wondered why the murals, the sculptures of Ramkinkar Baij, can’t be protected similarly?”

The same year Ghose approached Jawhar Sircar, who was then secretary at the ministry of culture. “From there onwards, the experts took over as it was entirely technical,” says Ghose. “All I could do was wait. I had given up hope. Nothing moved for years. And the Visva-Bharati authorities did not appear too keen to pursue the matter.”

Getting the heritage tag isn’t easy as it involves multiple steps. First, the Government of India has to submit (through the Archaeological Survey of India) a tentative list of important natural and cultural heritage sites. A nomination dossier is then prepared and submitted to the World Heritage Committee. After the dossier is submitted, the World Heritage Committee gets the nominations evaluated by two advisory bodies. The World Heritage Committee takes the final decision if a site meets at least one of ten criteria.

A building of Visva-Bharati University TT Archives

But the nomination dossier had to be resubmitted as it had at first focused on the intangible aspects of Santiniketan. A 2010 report by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), a non-governmental advisory body to the World Heritage Committee, stated that Tagore’s philosophical work itself was not eligible for inscription on the World Heritage List. “What could be inscribed is the physical setting related to his work, provided that its Outstanding Universal Value has been demonstrated.”

Finally, the recognition

In August 2011, a meeting was held under the chairmanship of the director-general of the Archaeological Survey of India to discuss the various issues related to the resubmission of the nomination dossier in the light of the recommendations of the ICOMOS. It was at this meeting that it was decided the new nomination dossier on Santiniketan should be proposed under the second and sixth criteria.

According to the second criterion, the nominated site has ‘to exhibit an important interchange of human values, over a span of time or within a cultural area of the world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts, town-planning or landscape design'.

The sixth criterion states that the site has to ‘be directly or tangibly associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with artistic and literary works of outstanding universal significance’.

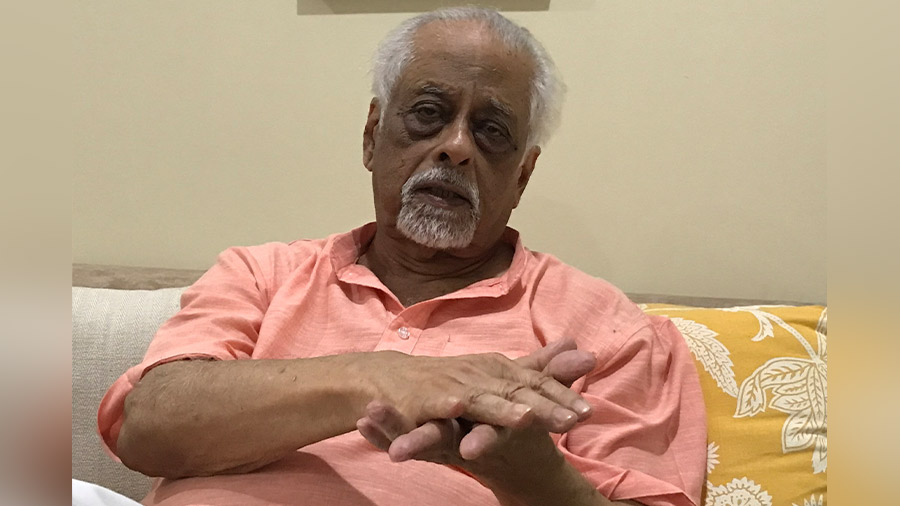

‘I believe Tagore is the key to the survival of mankind,’ says Ghose Arnab Ganguly

Thirteen years after the ICOMOS report, Ghose’s wait ended on Sunday with Santiniketan’s inclusion under these two criteria.

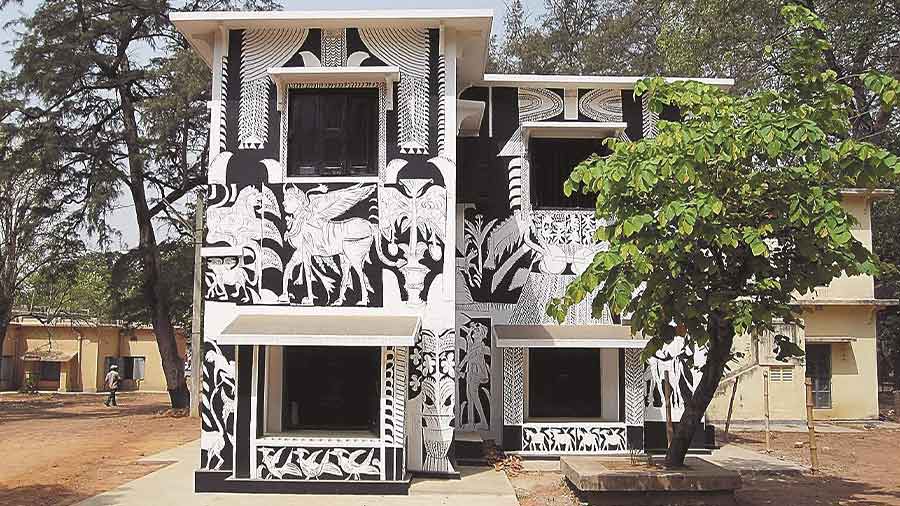

The statement on UNESCO’s website on the World Heritage List recognising Santiniketan says, “The architectural internationalism of Santiniketan as seen in its eclectic, inclusive architectural landscape was informed by Tagore’s unique brand of universalism that was a meeting of diverse cultural traditions from India (Buddhist, Hindu and Islamic origins), the Far East and (the) Americas to create an experimental collaborative, and co-authored built and unbuilt landscape for staging praxes in education, artistic learning, craft production and cultural syncretism.”

“I believe Tagore is the key to the survival of mankind,” says Ghose.

Flashback to a tribute

Long before Sunday’s achievement for Santiniketan, UNESCO had described Tagore as its “Guru”. In a 1961 message to the Tagore Centenary Celebrations in Bombay (now Mumbai), Vittorino Veronese, then director-general of Unesco, had written: “Tagore was in truth a living link between the East and the West. And so he willed it. His entire life he fought against narrow distrust of foreign cultures. He had faith in the fruitfulness of cultural intercourse and friendship. With this message he was and remains a Guru to Unesco, and it is both fitting and imperative that Unesco’s homage to Tagore should join that of the rest of mankind.”

The message was published in the December 1961 issue of The UNESCO Courier, which also included a piece by Satyajit Ray, who studied at Kala Bhavana for two years at Tagore’s insistence.

Satyajit Ray studied at Kala Bhavana for two years at Tagore’s insistence TT Archives

Following the September 17 recognition, the UN agency described Santiniketan as a “living embodiment” of universal ideas that were foundational to Unesco. “Twenty-two years after Tagore wrote of these ideas in his (play) Rakta Karabi, the General Assembly of the UN (had) adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.”

The UN’s 1948 Declaration document enshrined the inalienable rights of all human beings, one of the themes that Rakta Karabi, first published in book form in 1926, had dealt with, too, in its exploration of repression, freedom and redemption.

What next for Santiniketan?

An international recognition has been achieved but a lot remains to be done, says Ghose. “I want to remain hopeful that the Visva-Bharati authorities will be on their toes. A heritage committee will have to be set up. The World Heritage Committee keeps a tight vigil and de-recognition would be a huge slap in the face. Let us hope it doesn’t come to that.”