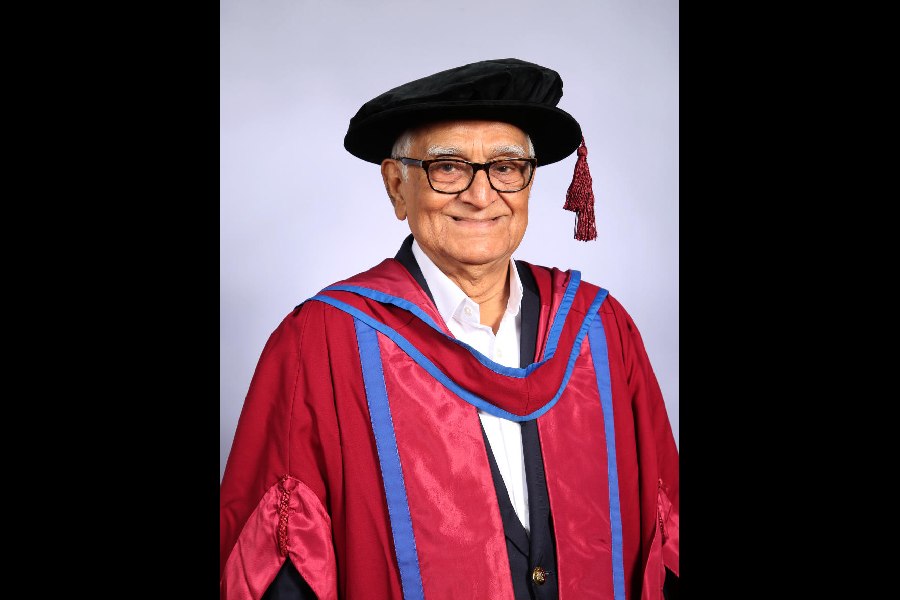

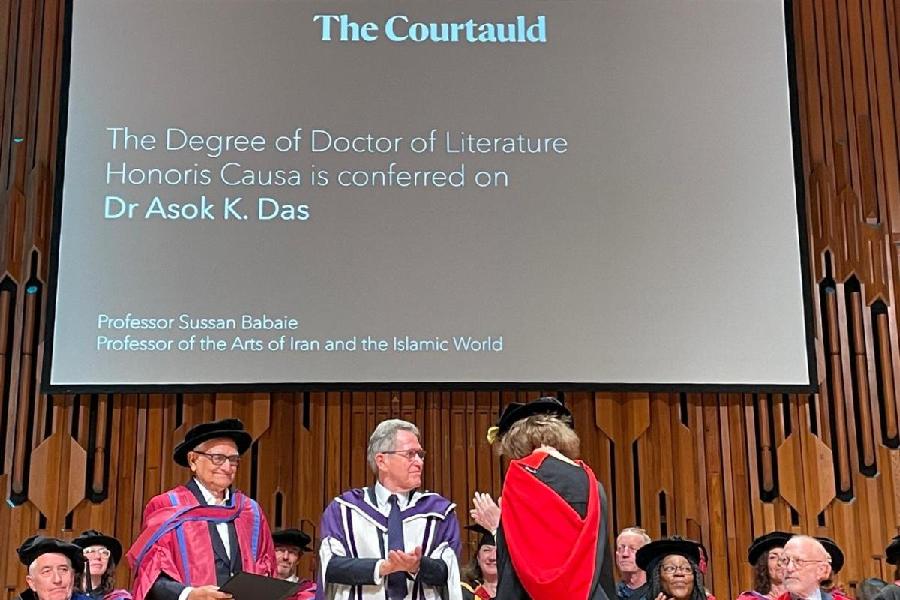

The Courtauld Institute of Art, an independent college of the University of London, on July 13 conferred an honorary doctorate (Doctor Honoris Causa) on distinguished art historian Asok K. Das.

A former director of the Jaipur City Palace Museum, Das specialises in Mughal and Rajasthani art and has authored several seminal works on Mughal art and culture. After studying postgraduate courses in Ancient Indian History & Culture, Law and Museology from the University of Calcutta, he joined the Indian Museum as deputy keeper, art, in 1963.

The next year, as a Commonwealth Scholar, Das started to work for his PhD at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. His PhD — Mughal Painting During Jahangir’s Time — secured him the Frederick Richter Memorial Award from the Royal Society of India, Pakistan and Ceylon. A senior visiting fellow twice over at London’s V&A Museum, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Freer Gallery of Art, Washington DC, Getty Museum, Los Angeles etc. Das has also served as the Satyajit Ray Chair of Visva-Bharati’s Kala Bhavana.

Das in an interview with Metro speaks about the state of the arts.

Q) You have been associated with museums in many parts of the world. Why are government-run museums like our Indian Museum in such a sorry state? How, on the other hand, has a more independently-run museum like the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya in Mumbai become successful?

A) The Indian Museum is technically not a government institution, as it is supposed to be run by the Board of Trustees. The board is almost non-functional and has no power and experience to run such a vast and multipurpose institution of national importance. The primary duty of the board is to recruit a good director, who would have the knowledge, experience, foresight and freedom to have a good team of curators and other functionaries. It should be free from bureaucratic interference. Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya has a good director, a functional board and is run mostly on private trust funds.

Q) How difficult is it for an art historian to work independently in today’s India now that culture and politics have become linked with each other in an obvious way?

A) Not very easy. It is not easy to get funding from government-run bodies. So long, the universities sustained them, but they are also suffering because of lack of financial resources. Politics has nothing to do here, it is a ploy to bypass the real issue.

Q) Are the Mughals an integral part of Indian culture or did they remain outsiders like the British?

A) The Mughals came from outside but settled here for good. From Jahangir onwards the rulers were more Rajput than Mughal.

They did not impose their religion or culture upon us, but developed a new culture by adopting the best of Indian culture carefully gathered from different parts of this country. It was easy for the people of our country to follow that and integrate with our life, living and culture. And it continues till this day.

Q) How did Mughal art and culture impact Indian culture and was it a salubrious influence?

A) The above is particularly true about Indian art, music, architecture, textiles and costumes, and food. Rajasthani, Pahari, Dakhni and all other later schools are deeply embedded in Mughal art. After all, most of the Mughal painters were Indians coming from different parts of India and practising their own traditions.

Q) Would you say that Akbar had a truly secular outlook and that he rose above bigotry? What are the differences between his and Jahangir’s contributions?

A) I wouldn’t use the word secular for Akbar, but he was genuinely interested in establishing a universal religion, Din-i-Ilahi. He was much ahead of his time. He realised that that was not practicable in his time. Jahangir was very different. He was a dilettante, intellectually not even close to his father.

Q) If Akbar was the father of Mughal art, how would you rate his illustrious descendants? Did this interest in the arts end with Aurangzeb who is said to have been a zealot?

A) Jahangir was a true connoisseur of art. Shah Jahan was more interested in architecture, jewellery and other luxury crafts. Aurangzeb was totally indifferent, busy in keeping his vast empire intact and, ultimately, ended as a failure.

Q) Did any of the Mughal rulers paint themselves?

A) Akbar knew how to paint, but his paintings have not survived.

Q) Was the contribution of the Mughals greater in the field of painting or architecture? I am not going into music.

A) In all three. They introduced khayal, ghazal and qawwali.

Q) Since little of the art and manuscripts of the Mughal period remain in India, is it difficult to study them here?

A) This is partly true. I must admit that there are substantial holdings of Mughal art in India, but they are not easily accessible making it difficult for the researcher.

Q) Is good research work being done in art history in India? What is the scene abroad like? What research are you engaged in now?

A) There are many bright young scholars here working in the field. At present the US, France and the UK lead the field. I try to keep myself engaged in continuing work in the fields I am familiar with, Mughal art and culture. I have an interest in various other related fields, including the study of the artistic heritage of Bengal from early times to the present.

Q: How did Mughal art and culture impact Indian culture and was it a salubrious influence?

Das: The above is particularly true about Indian art, music, architecture, textiles and costumes, and food. Rajasthani, Pahari, Dakhni and all other later schools are deeply embedded in Mughal art. After all, most of the Mughal painters were Indians coming from different parts of India and practising their own traditions.

Q: Would you say that Akbar had a secular outlook and that he rose above bigotry? What are the differences between his and Jahangir’s contributions?

Das: I wouldn’t use the word secular for Akbar, but he was genuinely interested in establishing a universal religion, Din-i-Ilahi. He was much ahead of his time. He realised that that was not practicable in his time. Jahangir was very different. He was a dilettante, intellectually not even close to his father.

Q: If Akbar was the father of Mughal art, how would you rate his illustrious descendants? Did this interest in the arts end with Aurangzeb who is said to have been a zealot?

Das: Jahangir was a true connoisseur of art. Shah Jahan was more interested in architecture, jewellery and other luxury crafts. Aurangzeb was totally indifferent, busy in keeping his empire intact and, ultimately, ended as a failure.

Q: Did any of the Mughal rulers paint themselves?

Das: Akbar knew how to paint, but his paintings have not survived.

Q: Was the contribution of the Mughals greater in the field of painting or architecture? I am not going into music.

Das: In all three. They introduced khayal, ghazal and qawwali.

Q: Since little of the art and manuscripts of the Mughal period remain in India, is it difficult to study them here?

Das: This is partly true. I must admit that there are substantial holdings of Mughal art in India, but they are not easily accessible making it difficult for the researcher.

Q: Is good research work being done in art history in India? What is the scene abroad like? What research are you engaged in now?

Das: There are many bright young scholars here working in the field. At present the US, France and the UK lead the field. I try to keep myself engaged in continuing work in the fields I am familiar with, Mughal art and culture. I have an interest in various other related fields, including the study of the artistic heritage of Bengal.