On a fateful day in the year 1977, a frail old man had set out from his remote village in West Bengal. He walked with a slight stoop, the years no longer light on his three-score-plus body. The night before, he had even dreamt of his own death. He travelled far. And the farther he went, his story travelled too, away from the desolate infirmity of age, reversing as it were the passage of years. Just as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Benjamin Button had grown younger as he grew older.

To Delhi the old man went first, borne by his now 13-year-old story, where people received him with applause. From there he went to Bhopal, where too they greeted him well.

In 2019, he crossed the country’s borders and reached Kazakhstan, where leaders and ministers seemed to have been enthralled by his tale. And finally, almost 45 years since he set out from his village one crisp morning for a 20-mile journey of hope, he arrived in the US, restored in life what fiction had denied.

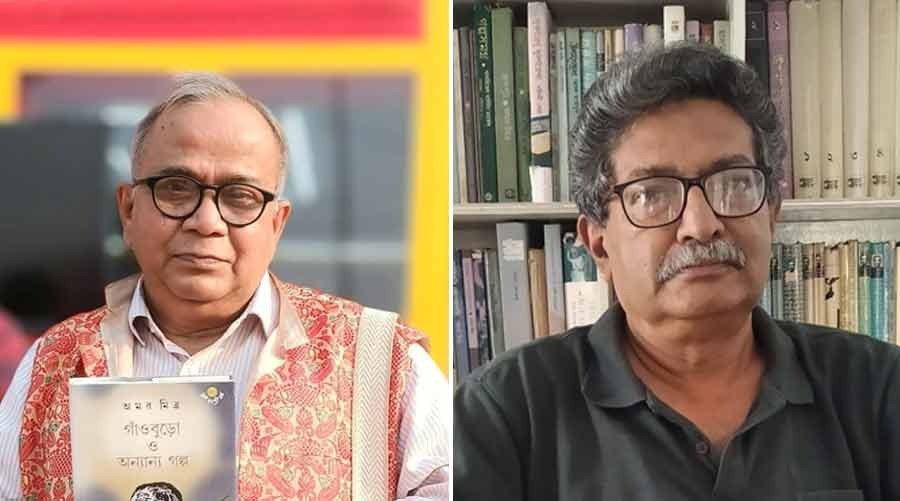

Writer Amar Mitra’s story, The Old Man of Kusumpur, has recently been awarded the O. Henry Award, the oldest major award for short fiction in the US, in the latest recognition for the tale that has triggered interest wherever the author has taken it.

Gaonburo, or The Old Man of Kusumpur, was written in the 1970s, but the story has revived itself every alternate decade ever since. In the early 1990s, it had been translated by Anish Gupta, a senior journalist based in Kolkata. The translation was done for a literary workshop in Delhi, where it received much adulation. Then, speaking on the story in 2019 at a literature festival in Kazakhstan, the author had got an overwhelming response. In its elusive search for hope, the story of the old man had found resonance again.

The story is about Fakirchand from Kusumpur, a stubborn old man whose failing health could not stop him from hitting the road in search of answers — solutions to the condition called life, the disabling cocktail that has forever flattered to afflict the human race.

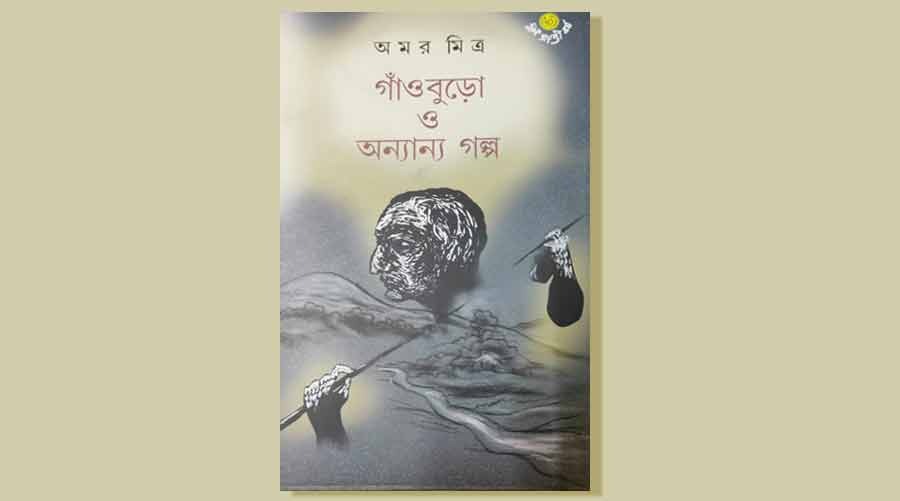

The front cover of 'Gaonburo and other stories' Courtesy: Amar Mitra

Real inspiration, mythical feel

A mythical tale at one level, the story draws inspiration from the author’s own life. As an official of the land reforms department of the state government, Mitra had to travel to remote villages of Midnapore, then an undivided district. Just like the author, his character Fakirchand too sets out on a long walk.

The old villager, a lonely widower abandoned by his son, wants to meet the Big Man who has all the answers to his problems. Maybe, the Big Man would also help him find a bride. His cataract-clouded eyes light up at the thought.

Sometime into his journey, Fakirchand encounters a dark-skinned man playing a flute. The dark-skinned stranger, Chhotosona Mandi, is in love with a woman named Bishnupriya. But Bishnupriya’s father does not approve of the match. The stranger haggles with Fakirchand. If he managed to get him a solution from the Big Man on how he could get married to his beloved, he would help Fakirchand cross a canal. Fakirchand promises that he would ask the Big Man — whose word made things happen — for a solution. For Indian readers, the allusion shouldn’t be too hard to grasp. Even the Gods cannot seem to escape the terms of being born as mortals.

But myth is not all that the story has to offer. Mitra’s long walks into the interiors revealed to him the crushing burden of families who live on the edge, such as the Adivasi villagers who continue to struggle for their livelihoods and their rights.

In the story Fakirchand comes across a dancing group of Santhals who lament that they can no longer observe their Salui festival the way they once did. The forest, their home for centuries, has changed with the times, bound by rules and regulations.

It’s not just the Santhals. Many such marginalised communities and their generations-old traditions have become extinct over the years. While some things have changed for the better since the time this story was written, forest dwellers have largely suffered from the unavoidable depredations of progress. No wonder then, the Santhals mistake the forest ranger to be the Big Man. Here too Fakirchand promises to get them help.

Plight of the marginalised

“I went to undivided Midnapore in 1973 when I was just 22. I spent eight years in the villages. I wrote the story when I was in a village called Kultikri, now in Jhargram district. A beautiful place it was. I spent a lot of time with the Adivasis and heard about their plight from their own mouth,” Mitra says.

Playwright and director Debesh Chattopadhyay, who has adapted the story of Gaonburo for the screen, shared with the author an experience of an incident that took place in Purulia while he was shooting for the film, now still in the post-production phase. Chattopadhyay had narrated the story to an old Adivasi man. After he had finished, the old man had broken into tears. “This is the story of my life!” he sobbed. “My life!”

The third person Fakirchand comes across is a man wasting away from leprosy. Shunned by society, he too sees a glimmer of hope when he hears about the Big Man and his limitless powers, and pleads with Fakirchand to ask for a cure for his disease. “If I am cured, I would like to roam the village streets again…” he says and shows Fakirchand the way to the Big Man who lives somewhere near the banks of the Subarnarekha river.

In the end, Fakirchand does not find the Big Man. The elusive figure with all the answers remains unseen. Fakirchand reaches the riverbank but stumbles and falls on his face, perhaps never to rise on his feet again. The message is difficult to miss: When reality sinks in, illusions can no longer sustain; hope is then just a mirage. The people he had promised help wait for him to return, but he doesn’t. The answers, the expected solutions, never arrive.

Although the motif of seeking answers is central to existential literature, Mitra says he has not been influenced by this relatively modern philosophy. “I have read (Albert) Camus and (Franz) Kafka. But I really adore Anton Chekhov, Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy. The books by these Russian stalwarts were available to us back then. Pragati Publications used to translate them and publish,” he says.

“We could not do what the Soviets did. They made their literature available in translations to the whole world. Our governments, institutions and intellectuals should have tried to take the gems that have been produced here in Bengal to the world.”

Mitra goes on to mention a few stalwarts of Bengali literature. “Bibhutibhushan (Bandyopadhyay), Tarashankar (Bandyopadhyay), Manik (Bandyopadhyay), Bimal Kar, Subodh Ghosh…. We could not give them a global platform. Think about Bimal Kar’s short story Janani. The West has been deprived.”

But surely, with the advance of the Internet, bringing global attention to Bengali literature should be a little easier? Mitra remains sceptical. “The West has not read Shyamal Gangopadhyay’s Rakhal Karai or the stories of Moti Nandi. The Sahitya Akademi and the National Book Trust should try to get the works of these stalwarts translated into other languages and provide them a global platform. I cannot speak about the literature of other provinces in India but, just in Bengal, so much great literature has been produced. Yet they remain concealed from the rest of the world for lack of translation.”

(Third from left) Writer Amar Mitra at the literary fest in Kazakhstan Courtesy: Amar Mitra

Cross-continental appeal

Mitra’s novels like Dhanapatir Char (Penguin Books is publishing a translation soon), Momenshahi Upakhyan or Ashwacharita often come to be associated with magic realism. But the author says it’s his own style, a natural inclination. Playing with myths is his passion, he says; myths that remain in our psyche unscathed by time. Perhaps this is why The Old Man of Kusumpur continues to charm readers, irrespective of their country or continent. If any further proof of that cross-continental appeal was needed, look no further than its latest laurel. The person who chose Gaonburo for this year’s O. Henry Award, along with the other short stories, was Mexican author Valeria Luiselli, the guest editor.

After the initial translation in 1990, translator Anish Gupta had revisited the story at the behest of the web magazine, The Commons. A few changes had to be incorporated to make it easier for the western audience. “The editors at The Commons asked me to make some minor changes. For example, at the beginning of the story, I had used the word quack (someone who pretends to have medical knowledge). We use the word quite liberally here. But the word is not very familiar in the West. I had to change it to wizard.”

Translating a story from one language to another is a strenuous process. Every culture has its own codes and its own inferences. “This is a challenge. What I kept in mind is that I have to get as close to the sense of the word as possible instead of looking for literal words,” Gupta said, speaking to My Kolkata.

Author Parimal Bhattacharya says Mitra winning the coveted prize, named after the writer who has given the world ageless stories like The Gift of the Magi and The Last Leaf, is a remarkable achievement for a Bengali author. “But I’d also like to see this as the triumph of the marginal voices, so well captured in The Old Man of Kusumpur, whose appeal has remained undiminished 45 years after the story was first published.”

Bhattacharya also named a few other Indian works to underscore what he claims is a shift in western perceptions. “A translation of Geetanjali Shree’s Hindi novel Ret Samadhi has been shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize. It’s the first novel translated from Hindi to be in contention for the prestigious prize. There, too, it’s the voice of an old, ordinary woman that runs through a 700-page story,” he says.

“If we see these achievements alongside the considerable international attention writers like Perumal Murugan (in Tamil) and Vivek Shanbhag (in Kannada) are getting with their stories of life outside metropolitan centres, we can perhaps detect a shift in the western perception of what constitutes Indian literature.”