With Durga puja barely three weeks away, the idol-makers in the neighbourhood are praying for a turnaround. Though, with the fourth wave of Covid-19 almost a distant memory, things are looking up in this festive season, several factors are throwing a spanner in their works.

The city may have taken the streets twice over to celebrate the Unesco inscribing Durga puja of Kolkata on its Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, but the news has not reached these shanty workshops, from Ultadanga to Mahisbathan to VIP Road, where struggle for survival is the way of life.

The biggest hub of idol-makers in the locality is along Canal East Road, to the left of the Gouribari flyover. There are 38 workshops lined by the Circular Canal. “The government created this steel framework for us 12 years ago,” says Subodh Pal, 63, who says he has been making idols for four decades now at the spot where his father had set up shop. The tall superstructure of rods has allowed him to create a mezzanine floor on which he has kept more idols.

Some idol-makers here, like Subodh, make only single smaller idols but many others venture into the more challenging Durga puja territory as well.

All of them agree that demand has improved this year compared to the last two autumns. “In 2019, I had made 100 Vishwakarma idols. In 2020 and 2021, I made 50 with a lot of trepidation. This year, I have made 85. Advance orders are not placed for Vishwakarma puja. Customers come and choose ready-made idols. They should start coming from early next week,” Subodh says.

Subodh had managed to sell his idols last year. But next door, Radharani Shilpalay was not so lucky. Twenty of their Vishwakarmas remained unsold. “Those are the ones you see lined up outside. We do not have time to make any more this year as Durga puja is early (from October 1),” says one of the five hired hands, layering the straw framework of a Ganesh idol with clay.

Most of the unsold idols he refers to have developed cracks. They will be repaired and coloured closer to the puja date on September 17.

Pradip Rudrapal, the famous idol-maker, is a resident of BJ Block and has his studio for years in Telengabagan, near Ultadanga. The average number of Durga orders he takes is 65. “That had nosedived to 30 in 2020. In 2021, I made 40. This year, the number has risen to 60. So you may say it is almost back to normal now,” says Rudrapal, who will be delivering idols to some of the biggest pujas of the city, like Sreebhumi and Singhi Park, Deshapriya Park and Jodhpur Park, other than his home and work backyards, BJ Block and Telengabagan.

Price-rise woes

Rise of prices of raw materials is creasing foreheads everywhere. At another idol-makers’ hub, Kabiraj Bagan, near Ultadanga and Dakshindari Station Road, Bappa Karmakar has been in the profession for 25 years. “In the last two years, our orders went down by almost 50 per cent. Now that everything is open again, we are still struggling. Owing to price rise in every sector, we have been forced to jack up rates of our idols. Clay, coconut fibre coir rope, bamboo poles, paint, etc cost at least 40 per cent more than they did earlier. We are facing a difficult time explaining our higher prices to customers,” he said. Karmakar has been supplying idols to several pujas in Beleghata, Mahisbathan, Patipukur, Lake Town, Baguiati and Bangur Avenue for almost three decades now.

“Jinish er ja daam malik aar bnachbe na (Raw materials cost so much, the owner won’t survive),” sighs one of the hands working in the studio of Gopal Pal on Canal East Road.

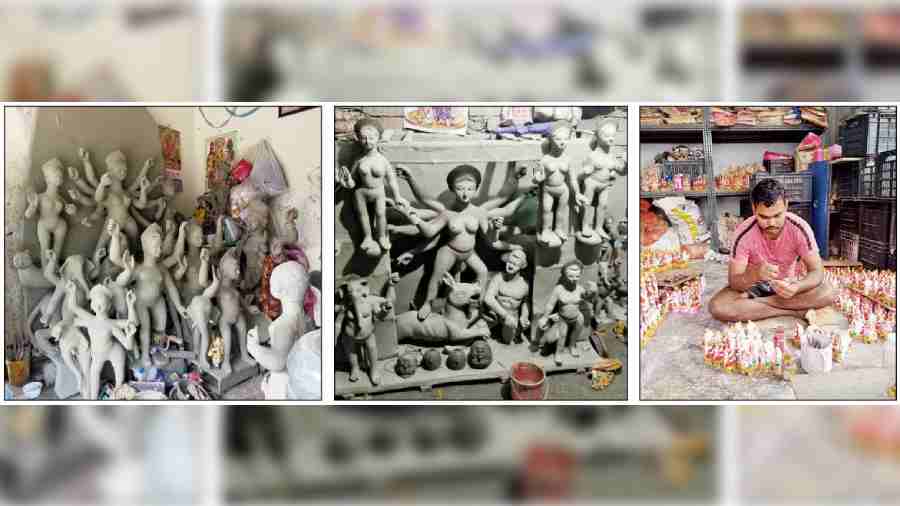

Idols in a cramped stall in Mahisbathan; a Durga idol in Kabiraj Bagan; an idol-maker gives finishing touches to Ganesh idols months ahead of Diwali. Pictures by Sudeshna Banerjee and Showli Chakraborty

The fear is echoed by Ganesh Pramanik. The 26-year-old, who used to assist an idol-maker earlier, had set up his own studio under the Sector V flyover. This year he has been displaced along with other encroachers by Metro Railway construction. Working out of a cemented stall provided to him and to others as rehabilitation by the government on the eastern fringe of Mahisbathan, he rues having quoted the same price as last year to clients. “The heights of idols have increased this year. A client who took an eight ft idol last year wants a 10ft one now. I could have taken more orders if I had more space.” But a trip to the market has dampened his spirit.

“Jute strings that cost Rs 120-130 a kg last year are going at Rs 160 a kg. Cost of every other thing, including decor, seems to have doubled. How can I say this to the client now since I have already quoted the idol price?”

Pradip Rudra Pal points to the crisis in the supply of bamboo poles. “While decorators can make do with green bamboo poles, we need the ripened yellow ones to make the chalchitra. But because of a shortfall in rain, they could not leave raw bamboo poles to rot in ponds and ripen. So the single bamboo pole that we paid Rs 125 for last year is priced no less than Rs 200 a piece.”

Cost of ornaments and decoration has also gone up. Dakshindari idol-maker Riju Mondal points out how even the basic weapons that are given to the idol, like the sword and trishul, made of tin plate, have become costlier.

“They can cost anything between Rs 5,000-10,000 depending on the size of the idol. Even for daaker saaj, which involves minimalist silver foil traditional jewellery, the ornaments could cost Rs 10,000-15,000. This cost also increases according to the idol size,” he says.

This rise is forcing him to seek a higher price. “This year a five-feet ekchala Durga idol is costing anywhere between Rs 20,000-25,000. A couple of years back, the same idol cost Rs 15,000-18,000,” Riju says.

Back to old ways

The rising cost has undone much of the eco-friendly initiatives that had been achieved through awareness drives. Bishu Palit specialises in painting the idols after they are dry. “The cost of paint has gone up by almost three times. So no one cares about the quality of paint any more. For chokshudaan on Mahalaya, for instance, we will use bright colours like red, yellow, pink and green. Most of them are lead paint. We know they are not environment friendly but the other variety has become very expensive. The moment you want eco-friendly paint minus lead, prices will go up. Customers want everything to be eco-friendly so that they can market their puja that way, but the sad truth is they will not pay higher prices for that,” he said.

Lack of hands

Labour cost too has increased manifold. Karmakar works with a team of four-five labourers at his Kabiraj Bagan studio. Earlier he would pay them Rs 200-250 per day during peak season. Now that has almost gone up to Rs 400-450 per day.

“It is very difficult to get extra hands. Earlier, I brought in five or six more labourers to help me during the festive season. But now I am getting a maximum of three people because I cannot afford the labour cost. Most people who work as labourers help in putting together the framework of the idol and get the right mix of entel mati and Ganga mati. It is a rare skill and not easily available in the labour market. One has to be trained in this skill to get it right. But with time, the availability of skilled labour is going down rapidly. A lot of trained hands are being hired by puja committees in other cities like Bangalore, Pune, Delhi, Patna etc,” he added.

Anil Pal, who has his studio on Canal East Road, is making two Durga idols less this year due to labour crisis. “I am making just 18 this year. Had I got a few more hands, I could have taken three-four more orders. Young people are not coming to this profession. It involves too much physical strain and little money. They are happier doing 100-day jobs provided by the state government,” says the 52-year-old idol-maker.

The lockdown and the fear of travelling out of town had made migrant labourers come home and stay back. “There was no shortage of hands last year. But now they are feeling confident about travelling to other cities again.”

Another setback has been caused by the slump in the market in 2020-21. “With Puja budgets plummeting, expert hands in this profession had no work and were forced to look for alternative means of livelihood like selling vegetables or agricultural work. Many of them have continued to do that. Possibly that’s why they did not come to seek work at our studios like they used to a couple of months ahead of Puja,” said Anil.

He himself set up a tea stall in front of his studio after the lockdown. “A few local factories have given me a yearly contract of supplying tea twice a day. So even in between idol-making, I shall keep the stall running,” says the owner of Joy Baba Loknath Shilpalaya.