A girl who would make weekday trips by S9 from her BJ Block house to Jadavpur University in the late 90s to attend classes in the English department has won an important prize in the UK for her work on travel literature.

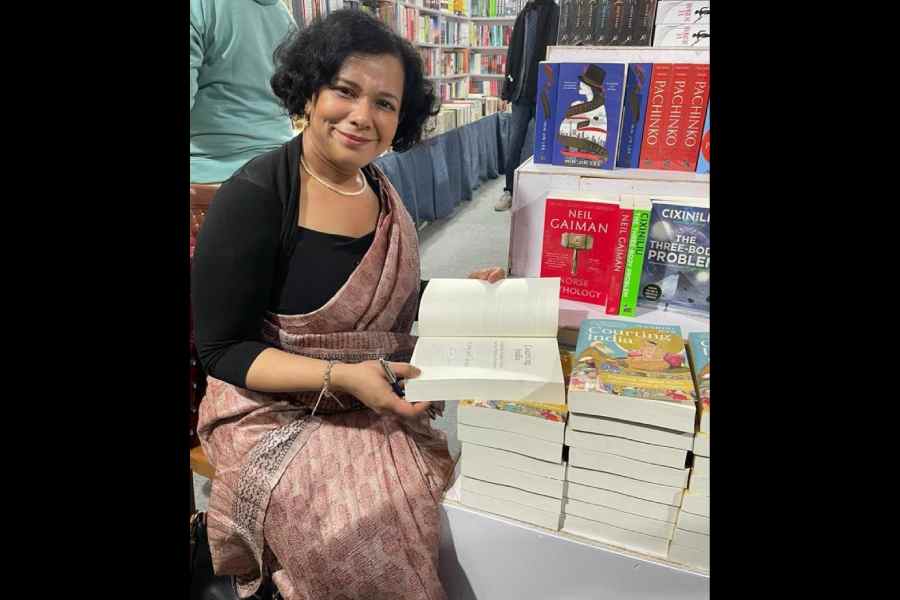

Nandini Das was at the book fair to talk about her book Courting India: England, Mughal India and the Origins of Empire, which has been declared the winner of the British Academy Book Prize for Global Cultural Understanding. Describing it as a “remarkable debut”, the British Academy website announcing the news says that the book “presents an important new perspective on the origins of empire through the story of the arrival of the first English ambassador in India, Sir Thomas Roe, in the early 17th century”.

A professor of early modern literature and culture at the English faculty of Exeter College, Oxford, Das works on 16th and 17th century literature, and travel writing in particular. “My area of interest is cultural memory, the ways in which we engage with a different culture or place and how much of that depends on the memories we have, including shared memory.”

Some years ago, Das was invited to write an article in a volume of essays on the global renaissance. “I wrote an article on Thomas Roe as I had come across his journal around that time and found it interesting. That later became a central chapter in my book.”

In the article, Das wrote about an anecdote of Emperor Jehangir getting his court artists to copy a Tudor miniature that Roe had taken with him and making a bet that Roe would not be able to make out the original from the copy.

“Roe stayed in my system since then. It helped that there is a huge amount of archival material in multiple languages in Europe and here.”

Das points out that it’s a narrow window in history that she deals with. “Elizabeth I, the longest reigning monarch at that time, had finally died and James VI of Scotland got on the English throne. Post-Reformation England had broken away from the Roman Catholic Church. That meant a lot of their old trade connections with Catholic Europe were starting to disappear and they were looking for new markets to sell their ware. The main export at this point was English wool. And they also wanted a bite of the luxury market in Asian goods that the Portuguese had monopolised,” Das said.

Nandini Das makes a point as Prof Sukanta Chaudhuri and British high commissioner Alex Ellis look on at a book fair programme Sudeshna Banerjee

Inverted equation

The East India Company had got their licence in 1603, just before Elizabeth died, and had been sending merchants since then. “But the Mughals gave them scant respect. England was a tiny country and not heard of back then.”

This equation, Das pointed out, has attracted attention to her book. “When we talk of India’s relation with Britain, we see it through the lens of the British Empire in the 18th and 19th century when Britain is the subjugator and India the subjugated. “But at that point in the 17th century, the relation was diametrically different. The Mughals were ruling over 1.24 million square miles and 150 million people. They were the second largest economy after Ming China. Roe writes that the Mughal state in India was too powerful and rich, and the British must not dream of colonising India. It’s an alternative view of what history could have been but was not,” Das reflects.

The Mughals, she said, were unwilling to talk to the English merchants as it was beneath their dignity. So the merchant pressure groups coaxed James I to send an ambassador to get a trading licence. James I was almost bankrupt. He appointed Thomas Roe while East India Company bankrolled his visit. Roe came to India with a big challenge — to convince the Mughals that they had to take the British seriously and then give him a trading licence.

In select company

Out of the nominations coming from across the world for the British Academy prize, six were shortlisted and the authors called to a panel discussion. Das was in Seoul, South Korea, on an invited lecture tour and joined the panel discussion online. Thus she also missed the grand event the next evening when the winner would be announced. “The other books on the list were very strong so I was delighted simply to be in that excellent company. My agent and the editor at Bloomsbury were present on my behalf at the award announcement. The event was being telecast live on the British Academy website, while I watched it, sleep-deprived and over-caffeinated, in my hotel room on the other side of the globe. It felt a bit unreal at 3am to hear my name announced on my tiny mobile screen,” she smiles.

Das discussed her book on stage at the fair with her former teacher at JU, Professor Sukanta Chaudhuri, a DA Block resident, and the British high commissioner Alex Ellis.

Before her return to the UK, Das also made a trip to Salt Lake to revisit her old family house in BJ Block though it has changed hands now. “I also visited relatives in CJ Block and met up with friends at City Centre. It felt terribly nostalgic and lovely to be back,” she signed off.