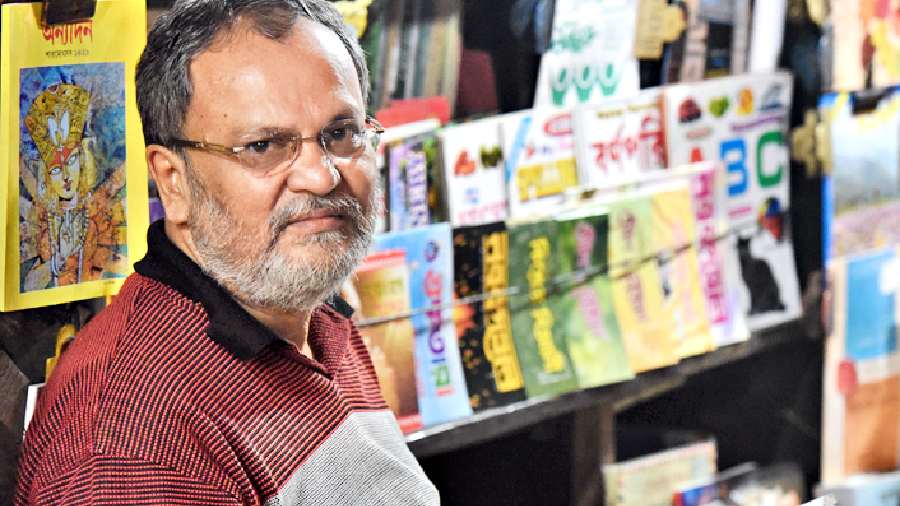

At the Rashbehari Avenue crossing, near Kalighat Metro station, in south Kolkata stands an old magazine stall. You can blink and miss it. If you don’t, you may discover in it many worlds.

Its few square feet rising from the pavement are packed with magazines of every kind, from lowbrow to literary, glossy to shabby, expensive to cheap, new to old. It is run by Kalyan Ghosh, 66, who is there for a while in the morning and a longer stretch in the evening. Known as Kalyandar dokan (Kalyanda’s shop), the stall is a local landmark. No one remembers its original name: Progressive Book Stall.

But once it was more than a local landmark. It was a place alive with conversations.

The stall was started by Ghosh’s father in the early 1950s. “It would also sell popular fiction then,” says Ghosh, who lives in the Lake Market area nearby. At that time the little magazines were starting. Radical young men bent on changing the world, and literature, often behind these magazines, brought them directly to the stall, but not at the expense of anything.

So the well-known Krittibas, which would have among its editors Sunil Gangopadhyay, Shakti Chattopadhyay and the controversial Malay Roy Chowdhury, or another early magazine that made waves, Anrinya, would be standing happily shoulder-to-shoulder with the latest Ultarath, Prasad or Nabakallol, leisurely afternoon pleasure reading, sometimes a little naughty, leading to siesta, often kept away from children. The world of books is a true democracy and the stall only attracted more people. And writers and talent from all fields. There was always a conversation to be had with tea and anyone could join it, whether you were a celebrity or a commoner. Perhaps the distinction was not so sharp then either.

“When Soumitra Chattopadhyay and Nirmalya Acharya started their magazine Ekkhon, they used to come here themselves with the copies,” says Ghosh. “Later, Chattopadhyay would perhaps call me to the College Street Coffee House to give me the books.”

The name Ekkhon had been suggested by Satyajit Ray, who had designed the first cover of the magazine and many later ones. Ekkhon, remembers Ghosh, had brought out special issues on Marx and Dante, which did very well.

“So many writers emerged from little magazines,” he says. “So many gifted people visited our stall.”

All the stalwarts of cinema came to the stall. “Mrinal Sen, Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak, everyone has come to this shop. Lyricists Gauriparasanna Majumdar and Shibdas Bandyopadhayay would visit the stall.” So did the theatre actor Satya Bandyopadhyay, who would be seen here very often.

Amritayan, the restaurant next door famous for its chop-cutlet (fried snacks) helped, as did Melody, the landmark music store just across. “Hemanta Mukhopadhyay would drop in at Melody. Who wouldn’t come to these two places?”

The conversation would not stop. If only one could write a history of the famous addas in Kolkata’s streets! The fact that they are not held any more points not only at the state of the city’s cultural capital, but also at the condition of its streets.

Ghosh began to visit the stall from the time he would return from his school, Kalidhan Institution in the Lake area.

“I loved books,” he says. As a child he was particularly drawn towards Swapankumar’s books. Swapankumar was a one-man industry who wrote several sensational series like Kanchanjangha and Pahelika, slim volumes that were breathless in their mix of crime, intrigue and passion, packed within blood-drenched covers. “I was hooked,” says Ghosh.

When he graduated from South City College in the late 70s, he naturally came to the store and started working here. “I never wanted to take up any other job,” he says.

He was not disappointed initially. “We did not have too many popular magazines then, but all sold well. Especially the Puja issues. We would have small trucks delivering the copies.”

He cannot stop talking about the variety of magazines that were found here.

After the establishment of the film society Cine Central, a number of other film clubs were founded and almost all the clubs had their own journals. Cine Central brought out Chitrabikshan. “We also had the journal Chitrabhaas,” says Ghosh. Light and Sound and Deep Focus were published in English.

“We had a large crop of sports magazines, too.” Some would bring out their magazine on the day of an East Bengal-Mohun Bagan match.

Things began to change from the 80s. Several things happened, most notably television. Afternoon leisure changed from reading stories to watching. Amitabh Bachchan towered over the national screen, blasting Bollywood into what was so far a somewhat sedate Bengali film-watching environment, also via the Hindi film dubbed into Bengali. Uttam Kumar’s sudden demise was a huge blow to Tollygunge.

The nature of popular entertainment changed. So did magazines. A new burst of magazines, well-produced and robust in content, came in. But on the whole, magazines would face a different future.

From the 90s everything changed rapidly, with technology and media. “The shop does not look like the old shop any more,” says Ghosh. “Once we opened shop at 6am, when we also sold newspapers. Pujaissue magazines would be ordered in copies of thousands. Now we open shop late morning, then again only in the evening,” says Ghosh.

“Now people have stopped reading. Earlier they would come just to look at books,” says Ghosh. It has been hard.

But even as we speak, a middle-aged woman buys a copy of Kishor Bhararti, another forgotten magazine for teenagers.

What has really not seen a decline, feels Ghosh, is the little magazine world. It has changed. “The literary has been replaced by theory or research. And the frequency of publication of the magazines has also changed,” says Ghosh. “But you still see in them a spark, a new idea.”

They keep coming to Ghosh and when they do not, Ghosh seeks them out.

Has he ever thought of closing the stall down? “Never. I love books,” he says. “My favourite writer was Kalkut (Samaresh Basu). I would stay up nights when I was young reading.” Now he does not read fiction so much, but he cannot do without books.

“I may introduce a thing or two to the stall to make the business more viable, butnever give it up,” says Ghosh.