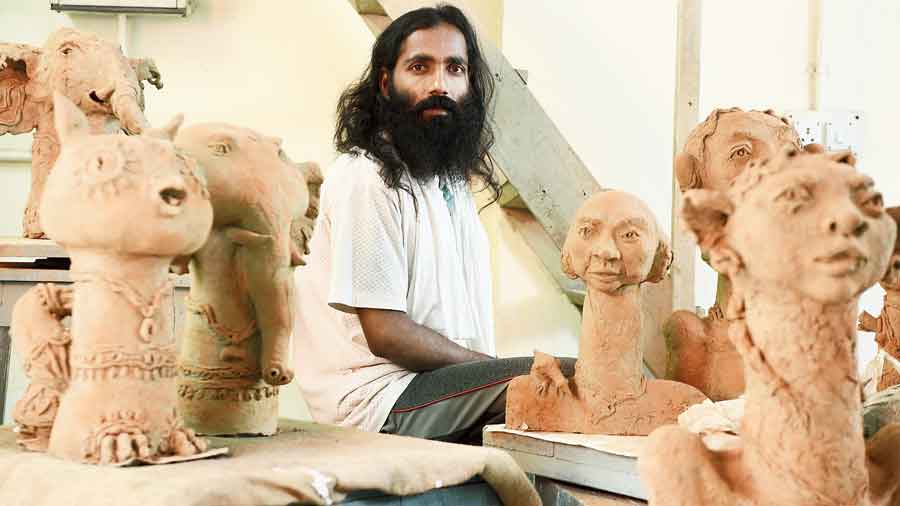

Prasanta Mandal is an arresting sight with his flowing beard and the quiet intensity with which his small, lean frame is bent over his table. He is working on a terracotta sculpture at the peaceful, spacious and leaf-fringed Lalit Kala Akademi studio in south Kolkata’s Keyatala just off Golpark. The clay figure looks like a small, surreal whale.

Around Mandal are other terracotta figures waiting to be fired. They are slightly human, slightly animal and quite whimsical, many of them with large, strange ears and other protuberances. As you pass him, he looks up at you with gentle, smiling eyes.

He is trying to put together a series on fish, he says. Or what he imagines as fish, but is not sure will fit the general idea of fish, a prospect that he seems to enjoy.

Mandal joined the studio at the end of December and is very grateful that he is here. A few years ago, it would have seemed an impossible dream for him. Mandal, 38, is the son of a farmer. He was born in Shirsi Kalaibari, a village along the Bangladesh border in Malda district’s Habibpur block, and grew up there, often thinking he could never escape.

From the time he can remember, he has been making clay figures. “Clay has been there with me. My hands were always dirty with it as I worked in the paddy fields. It was good entel mati (loamy clay), right for making figures,” he says. “I just feel a pull towards the earth.”

Around him at the studio are other sculptors and ceramic artists, who, like him, have been selected to work at the studio for a few months for a nominal fee. “This is my life,” he says, pointing at the emerging shape on his table. “Even if I starved.”

Growing up with his three brothers and an elder sister, Mandal was used to his father being away for long stretches, as he was a well-known folk theatre performer. Perhaps inheriting his passion from his father, when very small, Mandal had built himself a small oven where he fired his earthen figures. “On a Lakshmi Puja night, I made a Lakshmi idol in the moonlight. We did not have electricity then.”

He had no colour. So he learnt to make colours from the ash in the cooking oven or black on the pots, his mother’s alta, khori mati (chalk) and puin shaak flowers. “I didn’t even know that I had to hollow out the earthen figures.”

That he learnt from artist Ashim Goswami, a Malda town resident, who would mentor Mandal from the time he had to give up his studies in Class XI to help his family by working in the fields. His father died early. It made Mandal know despair.

“I would work in the fields, but felt no life there.” On Goswami’s advice, Mandal would attend art workshops in Malda town, or Baharampur and Raiganj in the neighbouring districts.

“Though not everyone in the city understands either”, says Mandal. He had to constantly face his neighbours who would question why he wasted time making clay statues. “But I would visit a place a little away from home, covered with trees. There was a post there with electric light. I would sit under it and work. I would work till two or three in the morning, feeling cold, but happy, free,” he says.

There he felt protected. “The BSF men would tell me to carry on working and not to fear. Men taking cattle to fields , carrying hansuas (long bent knives), too, told me to keep working; I had nothing to fear.”

On a visit to Malda town, at the Ramakrishna Mission, he had picked up a a book by Vivekananda because “his photograph on the cover drew me”. Later he found Vivekananda’s words would give him the strength to go on.

But despair is a steady companion. Once Mandal had even thought of giving everything up and becoming a sanyasi.

It was only about a decade after leaving school that he discovered the book that would fire his mind and change him forever. He had kept working with his two elder brothers in the fields, which had given their youngest brother the opportunity to study English honours. But one day in 2014, Mandal remembers, his uncle Nirup Bikash Mondal, a scientist, gave him Dekhi Nai Phire, the memoirs of Ramkinkar Baij, the painter and sculptor who was one of the pioneers of modern Indian art.

Just reading about his powerful, giant sculptures seemed to burn them into the young man’s brain. Baij came from a poor family too. “Ramkinkar seemed to be talking to me. He seemed to be talking about me,” says Mandal. He went through the book greedily, rapidly.

His uncle also gave him the life of Leonardo da Vinci, in Bengali. “I was fascinated by da Vinci’s anatomical illustrations based on his dissections, including of the female body,” says Mandal. As he was by Paul Gauguin’s life in Tahiti, which his younger read to him from the English.

“I now want a good Bengali edition of Van Gogh’s letters to his brother Theo,” he says. “I have to read them. Otherwise I will turn into a donkey,” he laughs. But he felt an irresistible pull towards Ramkinkar Baij, like he feels towards clay. He went to Santiniketan to look at the sculptures.

“I feel a pull towards things,” he says. “Even as a child I could not sleep because I felt drawn towards things. Shapes dancing in front of my eyes wanted to come out of my head,” he laughs again.

But the lack of a formal degree was bothering him. At the workshops or other platforms he would get awards or recognition as well. The doors that he wanted to open, so that he grew as an artist, may remain closed to him forever, he often feared. He tried to enrol at a Visva-Bharati course as well but was not selected.

His scientist uncle came to his rescue again. He brought Mandal to the Lalit Kala premises a few years ago. Mandal initially thought his lack of a degree, not to mention a fine arts degree, would matter here too. Finally he was selected for the studio space last year.

“My uncle is like a God’s gift to me. I wouldn’t have survived without him.” His uncle supports Mandal by also providing the rent for a room in Jadavpur.

Mandal mentions two other persons he is very grateful to for their support and mentoring: photo artist Prabir Kumar Das and celebrated terracotta artist Tarak Garai.

Das was instrumental in introducing him to Garai at a Raiganj workshop. Mandal had been told by others that Garai was almost “inaccessible”. From Garai Mandal learnt firing. He has worked with wood, fibre glass and stone, too, sometimes even travelling outside Bengal briefly, but terracotta is his medium, and dreamlike shapes touched with a jocoseness seem to be his form. He has no regrets about the long wait to be here. He is happy to get a start. “I am not an artist yet. I am just beginning to be one,” he says. “You can compare me to a seedling, which needs to be protected to become a tree.”

He misses one thing, though. A brick kiln started with a fire is not the same as the one as one run on gas here. “The dancing flames bring other dimensions to the clay. On gas the firing is brings a uniform shade,” he says.