A 9sq m stall in which barely five people can stand inside the counter is fuelling nostalgia, witnessing a relentless bustle of customers and registering bumper sales at the Book Fair.

The sight of the Sulekha ink stall straight ahead on walking into the fair through Gate 6 has become a talking point among not just the faithful few who still swear by fountain pens but among all 45-plus visitors to the fair.

“I wrote my Madhyamik exam with a bottle of Sulekha ink placed on the table by the clipboard,” said Rakesh Pal, a man in his 50s from Jadavpur. Many, like Snigdha Sarkar, led their teenage children towards the stall, explaining what a fountain pen was, and did not mind the wait in queue to reach the counter. Many young customers whom The Telegraph Salt Lake spotted scribbling on paper with pen at the counter sought tips from salesmen on how to hold the fountain pen as it was their first time writing with one.

“This response is completely unexpected,” says Kaushik Maitra, managing director of Sulekha Works Ltd, admitting that he had to be coaxed into applying for the stall by his schoolmate Suvobrata Ganguly. The stall is Sulekha's first appearance at the fair.

Equally astonished was his uncle, 76-year-old Manas Kumar Maitra, who sat on a chair outside the stall, savouring the sight as people browsed the ink brands on offer displayed in two showcases next to him.

This was sweet redemption for the architect who had hung the suspension of work notice at the Sulekha factory gate after which the company went into liquidation. “The day was January 1, 1989. It was a Sunday,” he recalled, adding that he also remembered the day when the court order was issued permitting reopening - January 26, 1994. “Who knew so many people still want to write with fountain pen!” he wondered aloud on Saturday.

The history

An advertisement of Sulekha ink on a double decker bus in Chowringhee in the 1940s

Sulekha has seen as many highs since its inception as there were lows in later years. Inks in the British era used to be imported. It was born of Gandhiji's desire to use a swadeshi ink. He shared that wish with his disciple Satishchandra Dasgupta, a retired chemist of Bengal Chemicals. Dasgupta came up with a formulation, named it Krishnadhara and started making it for distribution through khadi outlets, along with other swadeshi products. He soon shared it with the Maitra brothers, who were freedom-fighters, with the instruction to launch commercial production. “Thus was Sulekha born in Rajshahi, in undivided Bengal, in 1934. Of the two brothers, Nanigopal and Sankaracharya Maitra, the former became involved in manufacturing the ink, with help from the women of the house, and the latter in distribution, cycling from shop to shop,” says Suvobrata, a collector of antique pens. Production shifted to Calcutta in 1936, to a rented address in Bowbazar, and then, with sales booming, in 1946 to Jadavpur, where the bus stop near the factory is still referred to by the ink’s name. By 1948, the company's turnover had touched Rs 1 lakh, a magic figure in those days.

Two decades down the line, Sulekha also started exporting ink to Burma (now Myanmar), Central and South East Asia, England and Australia among other places. Their product portfolio had expanded to include fountain pen, rubber stamp, stencil, phenol, sealing wax and different types of glues.

In 1981, the United Nations asks Sulekha to help set up ink factories in Africa to transfer their knowledge and expertise. The first such factory was set up on a turnkey basis in Kenya, which Sulekha was to manage for the first two years before handing it over. At home, around 1984, a market survey by Mode pegged Sulekha's eastern India market share at 89 per cent.

“Satyajit Ray used to write with this blue-black ink which changes shade over time. Sulekha finds mention in both his book (Samaddarer Chabi) and film (Jana Aranya, where a scene shows mass copying in an examination hall, with an ink bottle passing from table to table),” said Suvobrata, who is elder to Kaushik by a batch but met him not in school but later when he landed at the factory door as a pen collector. “Even in our school, Sulekha ink used to be sold from a counter,” the South Pointer recalls.

But the entry of dot pens around 1987 spelt doom for the ink makers. Kaushik, Nanigopal's grandson, was studying mechanical engineering in Jadavpur University when work got suspended at all factories in 1988. “We too had tried making dot pens in collaboration with a Bombay manufacturer. I used to test them,” he recalled. But that was not enough to check the slide.

Once the company reopened in 2006, Kaushik insists production was never stopped. But he shifted focus to floor cleaning agents and in 2011, a solar division was launched. “He was busy making sanitisers after the lockdown but I insisted that he gives the ink business another try,” said Suvobrata, who collects pens for three decades and has authored a book called PenTales.

The revival

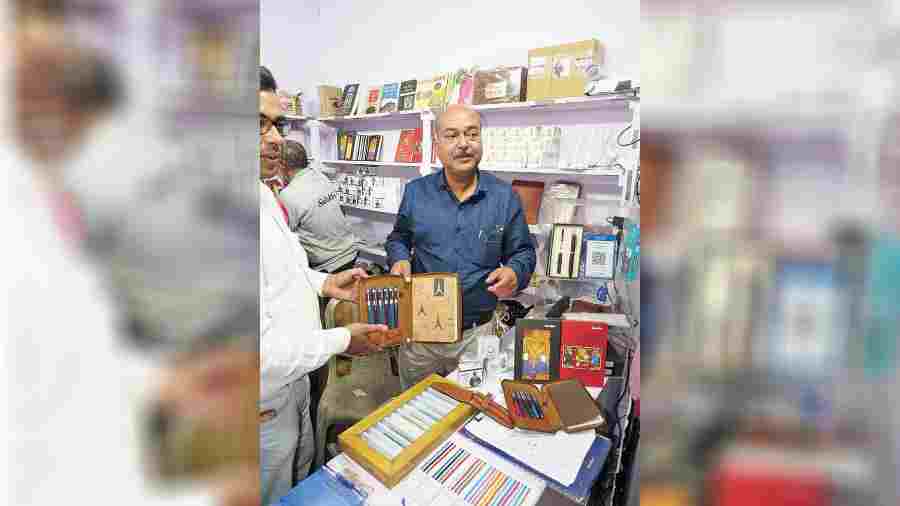

Kaushik Maitra (in blue shirt) displays fountain pens. Pictures by Sudeshna Banerjee

The Swadeshi range of inks was launched in 2020. Now the company makes 22 shades of inks. Earlier there were just three.

Several shades have stories associated with them. Sulekha Selam was created in tribute to language martyrs of Dhaka and Barak Valley. “We created just 21 bottles of dark red ink in 2021 and sent to a club called Fountain Pen Culture in Dhaka,” said Suvobrata, who was so involved with his friend's venture that he wrote the figures 2 and 1 in Bengali in blood from his fingertip to get the right shade for the brand's logo in remembrance of February 21. The club members demanded it commercially, so production was started. Another request came on the golden jubilee of the birth of Bangladesh that same year. “This time, we created a moss green ink keeping their flag in mind and named it Gorber Ponchash.”

Suvobrata Ganguly scribbles on an ink shade card. Sudeshna Banerjee

A teakwood box with ink in six pastel shades named Firingi Kali

Another blue black ink, called Ma, was created a year and half ago dedicated to Mother Teresa. The latest is a gray shade in a nod to poet Sukanta Bhattacharya’s immortal line: “Purnimar chand jyano jholsano ruti.” “The colour is that of roasted roti,” Suvobrata said.

Another product that catches the eye in the showcase is a teakwood case with brass accents. Inside it are a notebook and six antique glass bottles, reminiscent of bottles of aaltaa of yore, with labels in separate shades bearing the words Firingi Kali. “We found the formulations of these inks in muted pastel shades dating back to the 1930s. It seems a European lady artist, who was a friend of the family, had requested for ink shades to suit the climate at home. But there is nothing to suggest that the ink was finally produced,” Kaushik said. The box costs Rs 6,000.

Another limited edition item, Sulekha Swaraj pen, owes its existence to a chance discovery. “We found 140 old models of our pens without nib and feed. We managed to procure some missing parts from antique dealers and have managed to put together 70 pieces. Fifty of them are on sale at Rs 2,500 apiece,” he said.

At the Book Fair, one item doing well is Hatey Khori, a combination of a pen and a small bottle of ink costing Rs 100, targeted at first-time fountain pen users. “In our childhood, we were told writing with fountain pen improves one's handwriting. We are speaking to schools to revive fountain pen use in children,” said Kaushik.

Suvobrata offers an ecological reason to make the switch. “Think of the non-biodegradable trash we are generating by using throw-away plastic dot pens. In contrast, fountain pens are passed down generations,” he argued. He also spoke of how children were also developing finger fatigue by writing with dot pen which requires excessive pressure. “Orthopaedics are recommending that they write two pages with a fountain pen daily,” he said.

As the queue gets longer, both uncle and nephew agree that they should have booked a bigger stall and Suvobrata quips: “It is easy to claim that the new generation does not use fountain pen. But did we supply them the ink all these years?”

What are your memories of using fountain pen? Write to saltlake@abp.in