Makers of a documentary film on human trafficking hope to take it to schools and villages across Bengal to raise awareness about a scourge that makes hundreds of girls — and in some cases, boys — disappear from the villages every year.

A documentary film, titled Malaise of Mankind, was launched on Saturday at Max Mueller Bhavan and is now available on YouTube. Funded by the German consulate general, the film, said consul general Manfred Auster, targets potential victims who may be lured so that they stop and reflect before they walk into the trap. “We want to enhance their capacity to say no,” he said, before they are “trafficked against their will, ending up in prostitution or as house slave or in underage marriage”.

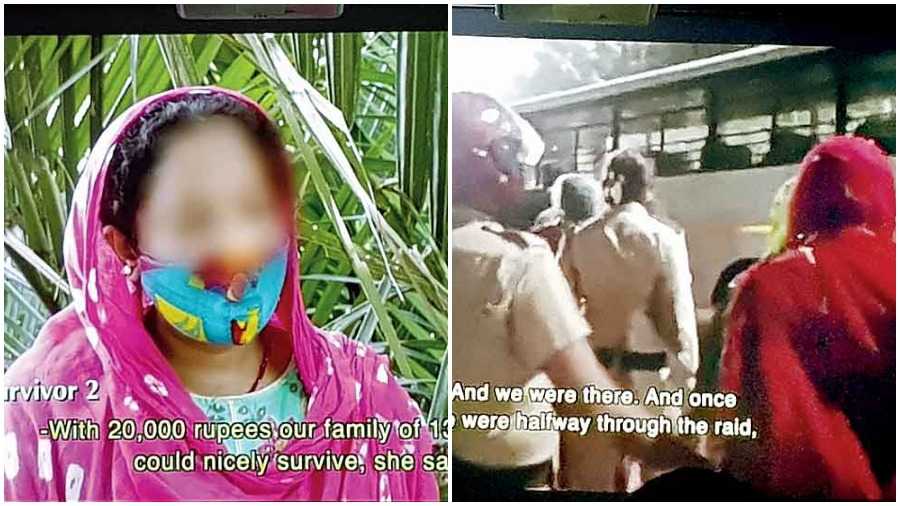

The 94-minute film interviews dozens of survivors, other than social workers and key administration members. From a student drugged with a handkerchief held against the nose by strangers on way to school to a mother of a two-month-old taken to Mumbai and sold off by her husband, the circumstances and agents of trafficking vary. The destinations of the trafficked too range from Kashmir to Chennai, Haryana to Mumbai. “There is not a village in Kashmir without a girl from Murshidabad,” says a social worker in the film.

“We shot over six months this year, traveling from Canning to Jalpaiguri to the Sikkim border. We also went to Haryana where girls are being taken as brides to address a lop-sided gender ratio and then forced to service all the brothers in the family,” said director Abhijit Dasgupta, the founder-secretary of Kolkata Sukriti Foundation.

Sometimes the family members are unaware of the consequences of what they think is a suitable marriage. “A buzz cut does not mean a BSF (Border Security Force) job, neither does a gold chain mean a well-to-do businessman,” warns another social worker. But often, relatives choose to turn a blind eye. The lockdown, activists say, has increased the tendency to marry off under-age girls by robbing the men of jobs. But poverty, feels Dasgupta, is not the cause, greed is.

Trafficking has no age bar. One strident voice in the film is of the inspector in charge of the Baruipur women police station Kakoli Ghosh Kundu, who had cracked a case in Baduria in 2016 when she was with the CID. “After child birth, women were shown a stillborn at a nursing home and then the baby was sold off to childless parents,” she said.

Neither is it restricted to girls. A social worker pointed to the demand for boys in Arab countries to service homosexual clients.

The film also deals with procedure that police often fail to follow, leading to low rates of prosecution, and the social stigma attached to survivors. “The family accepts the money she sends from her earnings in the flesh trade but is unwilling to take her back if the girl is rescued,” they said, pointing to the need for their social rehabilitation.

Prostitution, Dasgupta told Metro, is legal in some countries. “I did not want to get into the question of the freedom of choice to get in the profession but what is objectionable is if they are forced into it and treated like animals. I want to take the film to villages in video vans,” he said.