Only around 90 sweet shop owners out of close to a lakh in Bengal have applied for and obtained the right to use the GI (geographical indication) tag for Banglar Rasogolla in five years.

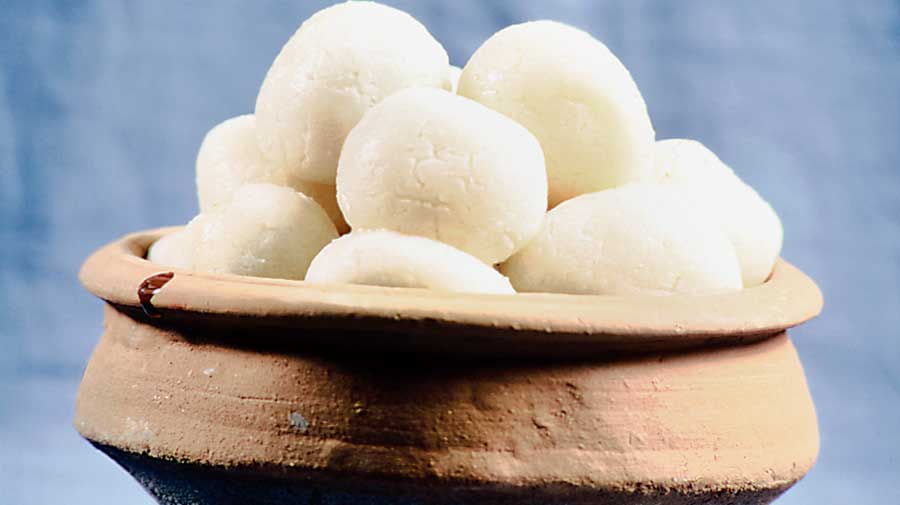

In 2017, Bengal’s rasogolla, the spongy ball of chhana dipped in sugar syrup, had got the GI tag. Many had then thought that it would automatically bring it on a par with Darjeeling tea or Champagne.

Senior officials in the state’s department of science and technology, who have been tracking the number of certified users of Banglar Rasogolla since the GI status was conferred in November 2017, said the eagerness to bag the “certified user” tag was missing among a majority of sweet shop owners because they believed it would make no difference to their sales.

A few who felt a certified tag would make a difference said they lacked the infrastructure, officials said.

“There isn’t enough awareness about the benefits of becoming a registered GI-product user and how it would help in positioning their business on a bigger scale for a majority of the sweet shop owners,” said Mahuya Hom Chowdhury, senior scientist with the state’s department of science and technology.

“For a majority of shop owners, the desire to step out of the comfort zone and embrace something new for rasogolla is yet to come.”

Since 1868, when Nobin Chandra Das was credited with discovering the white spherical cottage cheese dumpling in sugar syrup from an obscure corner of Bagbazar, rasogolla in Bengal continues to be made in different ways by different sweet shops with some confectioners using semolina or even white flour with cottage cheese.

But for one to be tagged Banglar Rasogolla, it has to meet several specifications.

The dumplings have to be made of pure chhana. No starch can be added. Careful kneading is recommended because the ‘mouth feel’ of a Banglar Rasogolla would depend on how well this has been done. The spherical dumplings should weigh around 10gm each. The syrup needs to be light — the stipulated sugar concentration is 30 to 40 per cent — and have a transparent appearance.

“The chewiness and hardness of Banglar Rasogolla are lower compared to the ones made in other states, including Odisha, Jharkhand and Bihar. Average moisture content is about 50 per cent compared to 55.49 per cent for others,” said a senior official of the West Bengal State Food Processing and Horticulture Development Corporation Limited.

Several sweet shop owners said there were several challenges in meeting the requirements, including creating a system of testing the products in labs and ensuring the right percentage of moisture with the help of proper gadgets.

“When the syrup is light, for instance, it gets difficult to maintain the freshness of rasogolla for a long time. The product will turn stale earlier if dipped in a light syrup compared to the one that we use,” said a sweet shop owner who requested not to be named.

Members of Mishti Udyog, an umbrella body of sweets and savouries entrepreneurs in the state, admitted not enough was being done to spread awareness of the benefits of becoming a registered user for Banglar Rasogolla.

“The two years of pandemic served a severe blow to the industry and nothing much could be done about holding awareness drives for sweetmeat owners. We have decided to start reaching out to the shop owners in Kolkata’s fringes from our Udyog before venturing into the districts,” said Dhiman Das, director of KC Das and the great-great-grandson of Nobin Chandra Das.