Of all the crises inflicted by the pandemic, the education crisis is the worst, development economist Jean Drèze said on Thursday.

“The worst aspect of Covid is the educational crisis. Because the health crisis, hopefully, will end soon. Even the economic crisis would be over. But the educational crisis is going to haunt a whole generation of children throughout their lives,” he said.

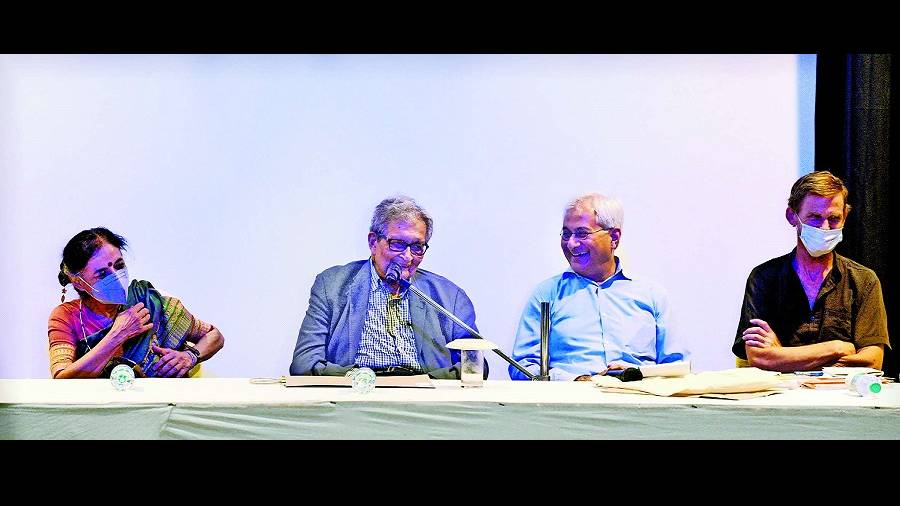

Drèze was part of a panel discussion on Back to School at the Amartya Sen Research Centre.

Apart from Drèze and Sen, Anita Rampal, professor of elementary and social education in Delhi University, and K. Srinath Reddy, cardiologist and president of the Public Health Foundation of India, were the other panellists. Reddy attended the meet virtually.

The discussion focussed on what the pandemic “has taught us with regard to schoolchildren and the priorities we need to keep in mind as schools physically reopen after two years of pandemic-related lockdowns, isolation and closures”.

A.K. Shivakumar, development economist, teacher and the panel chair, said it was reported that India imposed the second-longest Covid shutdown of schools after Uganda.

“Even before Covid, the neglect of basic schooling was reflected in the stagnant levels of public spending. Also worrying is the rapid expansion of an unregulated private sector in the school system,” he said at the outset.

Drèze spoke of his learning in the last 20 years in development economics of the “overarching importance” of education for the quality of life, economic success and democratic participation.

The crisis, Drèze said, had exposed in a “very stark way” that there is a conflict in the education system between the privileged and underprivileged children.

“The tendency of education policy is to settle the conflict in favour of privileged children,” he said.

“The impression that was created was that online education was adequate when it was practically of no use to a vast majority of poor children, Drèze added.

In a study done by Drèze and his colleagues in August 2021, in 15 states and cover-ing 1,000 relatively poor households, it was found that only eight per cent of children were studying online regularly.

“In many homes, they did have smartphones. You have to have money for recharging. The school has to send material, which was not always the case... There are so many obstacles,” he said.

Ironically, a day after the report, the prime minister made a “glowing statement” about the success of online education, said Drèze.

The discrimination continues as schools reopen for physical classes, he said.

“Now that the schools are reopening, they are simply trying to go back to business as usual... and doing very little to help children get back on track. Again, this is because of privileged children. They are on track. But the majority of children need some revision to catch up with learning deprivation,” Drèze said.

“The privileged children don’t want to be held up and you cannot have different policies for different children. So, things continue like before and children are given a promotion to the next class. Children who have forgotten how to read the Hindi alphabet are now given English textbooks,” he said.

“The worst part is that there is so little discussion around this,” he said.

Rampal spoke of the notion of democratic education.

“What is this notion of democracy we are still talking about? What about democratic education and schools where social citizenship is going to find a place because this is what our Constitution had said?” she asked.

“We know what is happening. It is not just the digital divide. We know what a Muslim child is going through, we know what a Dalit child is going through today, even when they come to school. When are these going to be addressed?”

A Covid report by Pratichi Trust titled ‘Staying Alive’ was released by the panellists before the discussion.