Every year, more than 1,00,000 people die by suicide in India, according to a conservative estimate.

The statistics don’t show the number of people affected by each suicide. In most cases, the bereaved families continue to live in denial and try to somehow cope with the stigma associated with suicide.

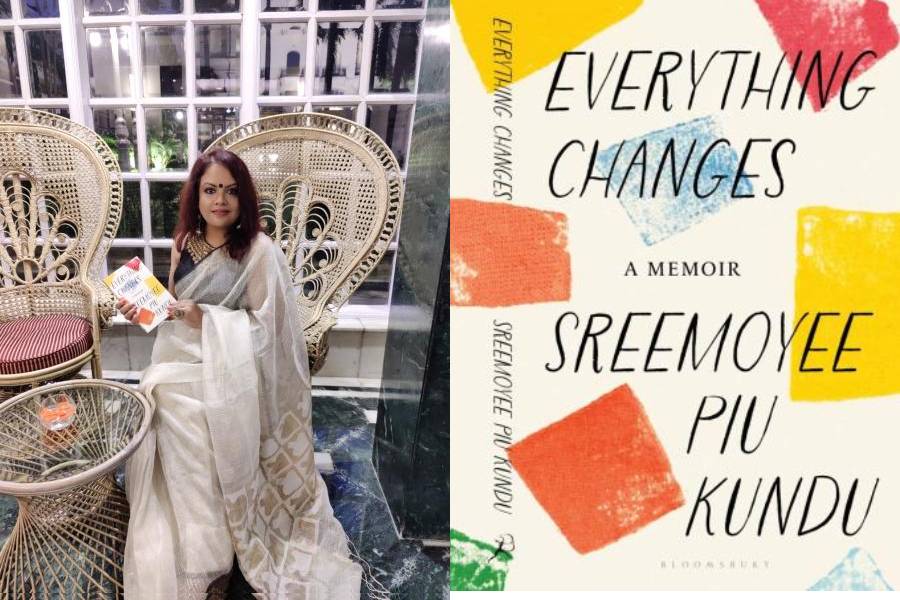

A book, set for a Friday launch in Kolkata, deals with the abandonment, trauma and stigma faced by the people left behind and a crying need for a safe space for the survivors.

Everything Changes, A Memoir, is by Sreemoyee Kundu. Her father took his life in 1981, when she was four years old. She came to know of how he died days before her board exams many years later, from an uncle who unmindfully blurted out what had been kept a secret from her.

“There is no vocabulary to describe death by suicide to the children of deceased parents, especially when suicide is seen as an act of cowardice. My mother had to face a near-complete exclusion from my father’s family. The book dwells on this, on how survivor families are almost always ostracized. Many relatives severed ties with her. My mother and her parents needed counselling to navigate their trauma and grief, but instead found refuge in silence,” Kundu told this newspaper.

Her parents fell in love at Presidency College. Back then, she said, her mother had no clue that her father had a mental health history, something that emerged years later during a formal medical diagnosis.

Kundu added: “I grew up around my maternal grandparents. Growing up, I never knew what a father was. I was bullied in school. The fathers of my friends would come to drop them and pick them up. I faced constant questions about my father.”

In writing the book, Kundu has done something unusual. Most people refuse to talk about a dear one who has taken his or her own life.

Psychiatrist Jai Ranjan Ram attributed it to “survivor guilt”.

“Suicide is a very personal loss. If someone very close to me dies by suicide, I will think if I am responsible. Could I have prevented it? Both these thoughts are kind of unbearable to live with. For most of us. Therefore, we don’t want to acknowledge this guilt and we go into denial for our own survival,” he said.

A total of 1,64,033 suicides were reported in the country during 2021, according to the National Crime Records Bureau. The number was 1,29,887 in 2017.

Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, Bengal and Karnataka have consistently been the states recording the maximum suicides.

“Family problems” and “illness” are the top contributors, followed by a host of other causes from addiction to debt and poverty, says the report.

In reality, these causes are often overlapping, said mental health experts.

“Research suggests that one suicide leaves around eight persons scarred for life,” said Molly Thambi, deputy director of Lifeline Foundation, an NGO that has been working for over two decades to break the stigma associated with suicide.

“But most families who have lost a member to suicide try to pass it off as an accident. The stigma is so strong that it spurs a denial. If there is no acceptance, how can there be a discussion?” she asked.

The foundation, in collaboration with police, has in the past put up posters offering help and counselling in several parts of the city.

“But no family is ready to talk,” Thambi said.

There are exceptions. A 31-year-old Kolkatan lost his elder sister when he was 18. She hanged herself. They were typical siblings, constantly fighting each other until that day.

The man and his parents were overcome with grief for a long time. But they did come to accept the reality, which they did not hide from anyone.

“I used to share the same room with her. We slept on two beds. My parents did not want me to sleep in that room after her death. But I knew I had to wake up and look at the empty bed. It was tough. But it was my road to acceptance,” said the man, now based in Mumbai, where he works with an online cricket news outlet.

He pens heartfelt notes in his sister’s memory on social media.

Some are led to acceptance by inspiration, from the likes of Kundu.

When she turned 40, Kundu, who had turned to Buddhism, performed her father’s funeral at a Dhakuria monastery.

“That was the first time I opened up about my father. I penned a long post on social media, giving my father’s name. I wrote about his depression. The fact that my mother and I are survivors. I acknowledged not just the pain and grief of 40 years, but also the anger that I had harboured towards my father,” she said.

After she opened up, many survivors reached out to her, some from a group she founded. Kundu is the founder of Status Single, a community of single women that aims to dispel the stereotypes associated with the community.

“There is a member whose younger sister hanged herself when she was 18. She would always refer to this as an accident. But last year, the same girl organised her sister’s last rites at the same monastery. In doing so, she acknowledged the truth of her sister’s death and also celebrated the beauty and joy of her short life,” Kundu said.