Benevolent zamindar. Pioneer of the cooperative movement. But ultimately, a representative of the Raj.

Daniel Hamilton (1860-1939), who set foot in the Sunderbans 120 years ago, was discussed in detail at a south Calcutta auditorium on Monday.

Hamilton, a Scotsman, made India, specifically the Sunderbans, his second home. He secured a zamindari in Gosaba, where his bungalow is now a stop for package tours. But the man survives only as a vague legend.

Two former administrators who have studied him in detail did most of the talking at the Birla Academy of Art and Culture on Monday. The session was billed as an “epilogue” to the Tata Steel Kolkata Literary Meet, in association with Victoria Memorial Hall and The Telegraph.

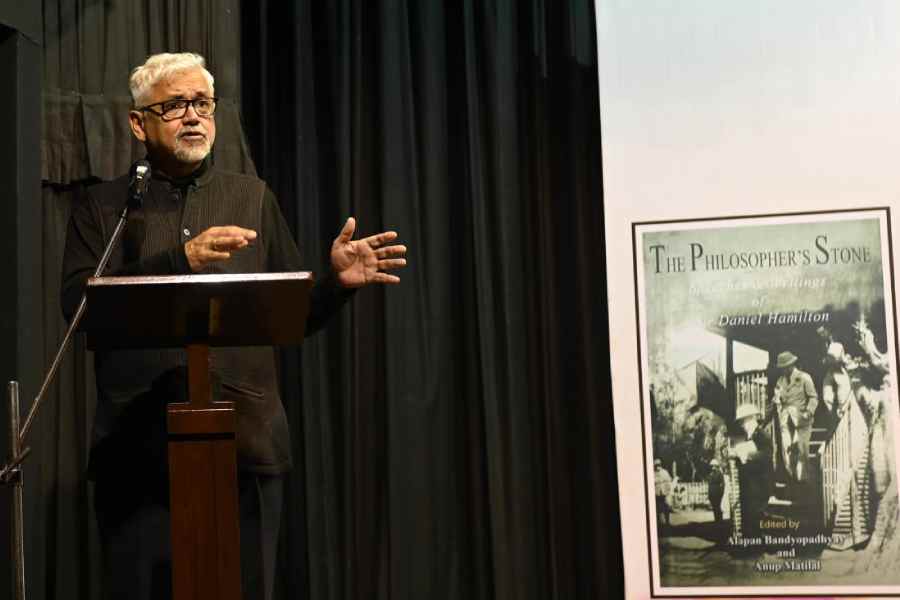

Alapan Bandyopadhyay, former Bengal chief secretary and now chief adviser to the chief minister, and Anup Matilal, former special secretary to the Bengal government, have co-edited The Philosopher’s Stone, Speeches and Writings of Sir Daniel Hamilton.

The book contains an article by Hamilton that too is titled “The Philosopher’s Stone”.

Bandyopadhyay first saw Hamilton’s writings during his stint as additional district magistrate of South-24 Parganas. The efforts that culminated in the publication of the book gained momentum during his return to the district, as “collector and magistrate”.

A new edition of the book was launched at the Birla Academy of Art and Culture by author Amitav Ghosh. He then delivered a brief address.

The introduction to the book says: “Hamilton was a benevolent zamindar with a zeal to reform the rural economy. But he was ultimately a representative of the British Raj.... He was also obsessed with the British idiom of improvement which had formed all efforts made by the colonial rulers to relate non-antagonistically to the ruled.”

Ghosh said this was bang on.

“I feel I have a certain kind of connection with Sir Daniel Hamilton because of my uncle. In the 1960s, he was the headmaster of the Gosaba school. Later, he became manager of the Hamilton Estate. In those years, we would often go from Kolkata to Gosaba to visit him. I have very vivid memories,” Ghosh said.

Ghosh’s book, The Hungry Tide, set in the Sunderbans, mentions Hamilton. After it came out, a man who identified himself as Hamilton’s nephew sent a message to Ghosh, saying that Hamilton was institutionalised in his last years, apparently after he became insane.

“He sent me a memoir about Sir Daniel Hamilton written by some member of the family where he described (his last years). It is a strange trajectory,” Ghosh said.

He then spoke of a contradiction.

“The problem really was that even though he talked about making cooperatives and all of that, he never handed over any land to the natives who came there to work,” Ghosh said.

“So, they became non-occupancy tenants, and later they just became sharecroppers. Later, that led to Gosaba ultimately becoming one of the centres of the Tebhaga movement.... So, despite all his idealism, ultimately, I don’t know if the (Hamilton’s) project was defensible or not.

“Because he encouraged large-scale settlements. These people are now in the path of climate change. Their lands are slowly but surely going under the water, destroying their livelihoods and leaving them destitute. So, whatever good intentions he had are now being swallowed up by the earth itself.”

After Ghosh’s address, the co-editors of the book were in conversation with Jayanta Sengupta, historian, teacher, author and director of the Alipore Jail Museum.

When Sengupta asked how the book had come into being, Bandyopadhyay began by saying: “This was not a story of discovering or detecting idealism in Sir Daniel Hamilton.”

He added: “We discovered an interesting sahib in Gosaba who required some degree of attention.... In him, we got some very complex and interesting interstices of history.

“We found in Hamilton not any pure White idealism but a quaint combination of Christian piety of the (David) Livingstone (the Scottish missionary and explorer) mode; orientalism — he kept referring to Akbar, Ashoka and others — a visible dislike for popular enfranchisement; a comprehensive hatred for Leninist communism; he championed for a non-English Scottish project of a paternal governance.”

Matilal said: “He came to India at a very early age as a businessman. But he cherished a dream of ameliorating the sufferings of the poverty-stricken people of the colony. With this dream, he started the settlement (in Gosaba). He not only claimed the land and invited people to come and live there; he planned to have a cooperative movement. He took a lot of time to start the movement in Gosaba but he did it. He can be called the pioneer of the cooperative movement in India.”