Children are back to school after the pandemic but the learning gap is far from gone, suggest the findings from West Bengal of a nationwide survey.

The state has fared better than the national average in multiple parameters but learning is yet to reach the pre-pandemic level, showed the Annual Status of Education (Aser) Report 2022, released by NGO Pratham, which conducted the survey, on Wednesday.

In West Bengal, one in three children (around 33 per cent) in Class III can read standard Class II-level text, according to the survey that was carried out from September to November 2022. The corresponding national figure is one in every five children.

While the percentage in West Bengal was close to 40 in 2018, it dived to 29.3 in 2021.

The Aser report covered 3.74 lakh households and some seven lakh children aged between three and 16 years.

A panel discussion on the findings of the report was organised during the day by the West Bengal Liver Foundation and Pratham.

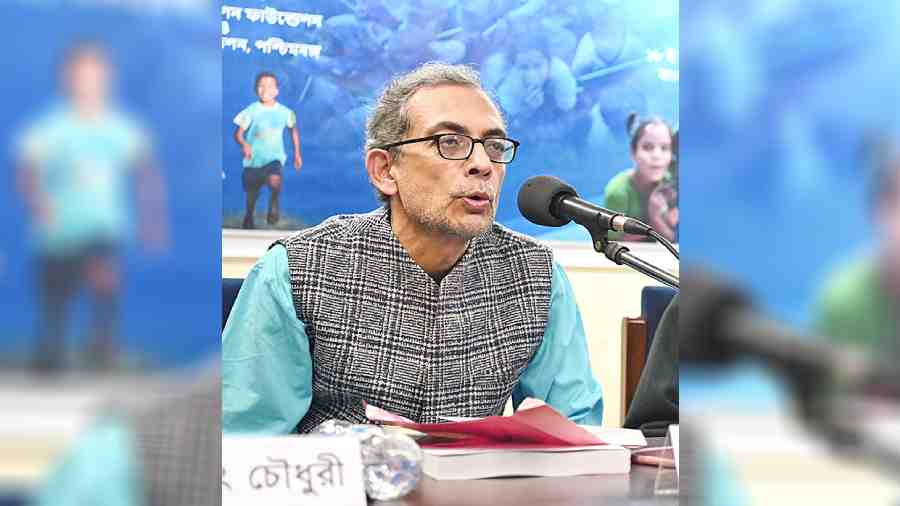

Sukanta Chaudhuri, emeritus professor at Jadavpur University and a panellist, said the learning deficit was more acute in relatively younger children.

“Between 2018, before Covid, and 2021, after Covid, there has been a general decline. But Class V students have been more affected than Class VIII students. Because children in Class VIII in 2021 had attended school for a few years before Covid. They are familiar with letters and numbers. But children in Class V now have learnt nothing in the past two years and have forgotten what they had learnt a couple of years before that. The learning deficit is more acute in relatively younger children who have not had the chance to strengthen the foundations of their learning,” he said.

“The children enrolled in Class I in 2020 have learnt nothing in the past two years. They have, effectively, started going to school in 2022. They have actually been promoted to Class III while still illiterate.”

Some of the other findings of the report that were shared on Wednesday:

- In 2022, 92.2 per cent of the children in West Bengal were enrolled in government schools. The percentage of students enrolled in government schools in India last year was 72.9 per cent.

- In 2022, 32.4 per cent of Class III children in government schools in West Bengal were at grade level in basic arithmetic. The corresponding national percentage was 20.2.

- Almost 75 per cent of the students in classes I-VIII in West Bengal took private tuition in 2022, the highest in India. The all-India percentage was 30.5. West Bengal is among the states with the lowest private school enrolment and highest private tuition takers.

Economist and Nobel laureate Abhijit Vinayak Banerjee, who was another panellist, said the high enrolment in private schools in many states pointed to a colonial hangover.

“There is very little difference between students of government and private schools. A question then comes up: why do parents spend on these private schools? Why do they spend on private tuition? What is important for parents? They want their children to clear Class X and Class XII and crack the test for a government job. This is a result of our colonial past. They tend to think what is the value of education if they cannot reach that stage,” said Banerjee.

“But studies from all over the world suggest that a man who has read till Class V learns and earns more in life than one who has read till Class IV. We still think the objective of school education is a government job or just another job. A change is needed here. We have to understand that every child can learn. The more she studies, the more she gains,” he said.

Subhra Chatterji, educationist and director of Vikramshila Education Resource Society, spoke of a “terrible inequity in the geographical distribution of teachers”.

Abhijit Chowdhury, a doctor and public health expert and the secretary of the West Bengal Liver Foundation, warned that the education system was “sinking gradually, like Joshimath”.

He called for “urgent remedial action”, insisting that “educational goals should not be seen through the prism of political colours”.