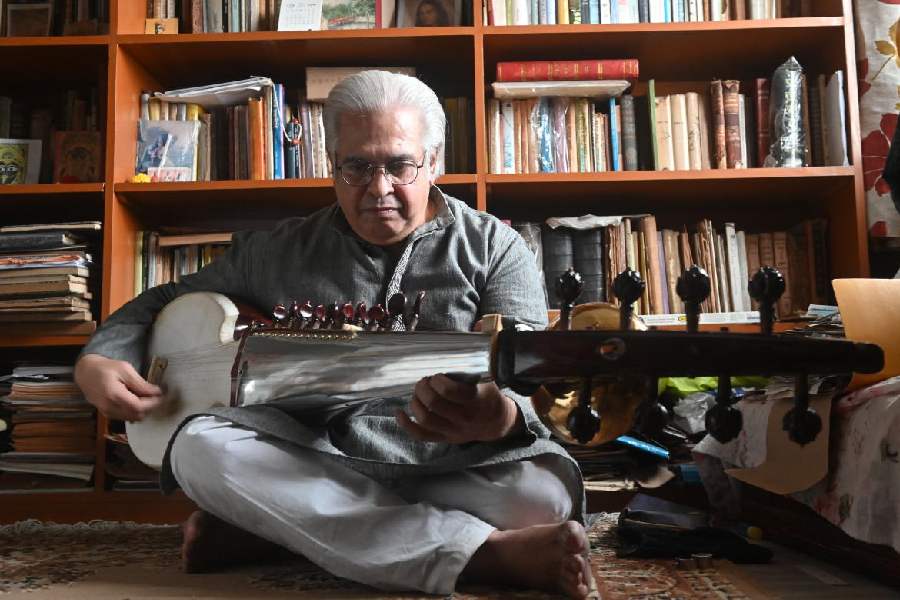

Anindya Banerjee grew up in a house of music. “Gaaner bari,” it was called. Banerjee, 66, is one of the leading sarod players in the city. He trained under the renowned sarod player Ali Akbar Khan.

The three-storey house, behind Deshapriya Park in south Calcutta, belonged to Banerjee’s maternal grandfather. His family had moved there, from Banerjee’s father’s house in Fern Road, which was not far away, when Banerjee was a small child, so that his mother could take care of her father.

Aradhana Banerjee, his mother, was a popular singer in the 50s and 60s in Bengal, and her brothers were musicians, too. The house, where she grew up as well, was as full of music as of rigorous training.

“My mother, when she was very young, had hair that reached her ankles. Her elder brother would tie her hair to the French windows in the hall, so that she wouldn’t move during her practice,” laughs Banerjee, 66, who now lives in Avishikta II, a residential complex on EM Bypass. Music is a demanding goddess, who wants the practitioner firmly in place.

Banerjee speaks about his association with Ali Akbar, much more than his own music. He speaks about his teachers and the teaching of music. He could have been many things. He was a sports champion (the sports gene was from his father’s side, he says) when he was in school in St Lawrence High School in the city. Later, he studied commerce at St Xavier’s College in the city, then law and cost accountancy. His interests are varied and include collecting many things, including rare books, posters, musical instruments —he also plays the sursringar —which he had revived, for which he received a senior fellowship from the centre, newspaper clippings, including matrimonial ads, stunning in their number and expectations.

He is a walking archive of stories and information about Indian music and culture, and a wonderful raconteur, with a robust sense of humour, a genial personality and an ear that can sharply dismiss a singer as having no “sur”, even if he is famous. But it is music that he pursued. “I would mimic my mother when she sang,” he laughs again. However, early in life he knew he would not be a singer, or a tabla or a sitar player.

“I would pass Hemen & Co, the landmark instrument shop in Rashbehari Avenue, and love the shining metal orb attached to a sarod. I wanted to play the sarod,” says Banerjee. When Banerjee was 10, he was bought a small sarod for Rs 140, and was admitted to the Ali Akbar College of Music, in Katukutu (which means tickling) Bhavan in Lake Market, where the master taught.

“We had classes every Wednesday evening and Sunday morning. The classes were held at different times because the ragas have to be played at their particular hours: morning, afternoon, evening,” says Banerjee. He has just played for us an alaap in Bhimpalasi, an afternoon raga, which has removed some of the gloom of a rainy, December afternoon.

What is it about the sound of music of the Maihar gharana, which was founded by one of the most revered musicians of India, Ustad Allauddin Khan? It is melodious and deeply resonant, but Allauddin Khan, who had learnt from many masters, brought together many influences and systematised the presentation of a raga, stressing on every aspect, says Banerjee.

Allauddin Khan’s training of Ali Akbar is the stuff of legends. The young Ali Akbar would have to practise for 18 hours a day, and not eat too much as flab would come in the way of practising. He would be severely beaten, says Banerjee. So much so that Ali Akbar’s mother had stitched for her son a shirt made of lep (quilt).

Banerjee has edited a hand-written journal of Allauddin Khan, written when he was in Calcutta in the late 50s. He is a prolific writer, with several books on music to his credit. Training at the Lake Road school was not exactly like what Ali Akbar himself had received at Maihar, but was rigorous.

The students had to sit on the floor on madurs, hand-oven mats, for hours for the lessons. Among other things, Banerjee had been strictly instructed not to perform in public before 12 years of training. About the time he joined this school, Ali Akbar had also started his school in California. He began to spend more time abroad and the school here suffered. It shut down eventually.

Banerjee then trained under Ali Akbar’s son, Dhyanesh Khan, who was a major influence, even as lessons from Ali Akbar continued.In 1979, Banerjee accompanied Ali Akbar to Bangladesh, at the invitation of President Zia-Ur-Rahman, and played the tanpura on stage and looked after Ali Akbar off it. This was the beginning of many years of travel with Ali Akbar. Just being around him was a reward. “I went with him everywhere, abroad and in India,” says Banerjee.

As in the first trip, he accompanied Ali Akbar always on the tanpura and took care of him. He also began to go to California for lessons from Ali Akbar. In the course of these years, at some point, he began to address Ali Akbar as “Baba”, after Ali Akbar had signed a letter to him as “Baba”. Banerjee also began to teach sarod abroad, in the US and the UK, and perform abroad, from the 80s. These sustained him. “Otherwise it is very difficult to survive as a musician,” says Banerjee.

He has performed in many places in the country and abroad, but two of his own performances are most memorable for him. In 1994, at Maihar, in Madhya Pradesh, where Allauddin Khan had lived, Ali Akbar built a mazhar for his father. On the morning of the inauguration, when people were yet to come, Ali Akbar requested him to play the raga Todi and the raga Gaur Sarang, as an offering for his father.

And in 2005, Banerjee was again requested by Ali Akbar to do something: not cancel a performance, despite the fact that he had received the news of his mother’s death thatday. Ali Akbar had done the same, he told Banerjee, who played the ragas Shyam Kalyan and Bageshri, his mother’s favourites. The book that Banerjee has written is an account of the streets, between the two signposts that define his life, in a way: Fern Road and Deshapriya Park. A lot happened in between.