Iffat Nawaz’s Shurjo’s Clan is a testament to her brilliance as an author as she presents a precise yet inventive retelling of the history of Partition. Nawaz, who had worked for over a decade in humanitarian and development projects in USA, Asia and Africa, discusses her motivation, the country’s history, her hardships, and more in an interaction with The Telegraph.

The title of your book is unique. What is the story behind it?

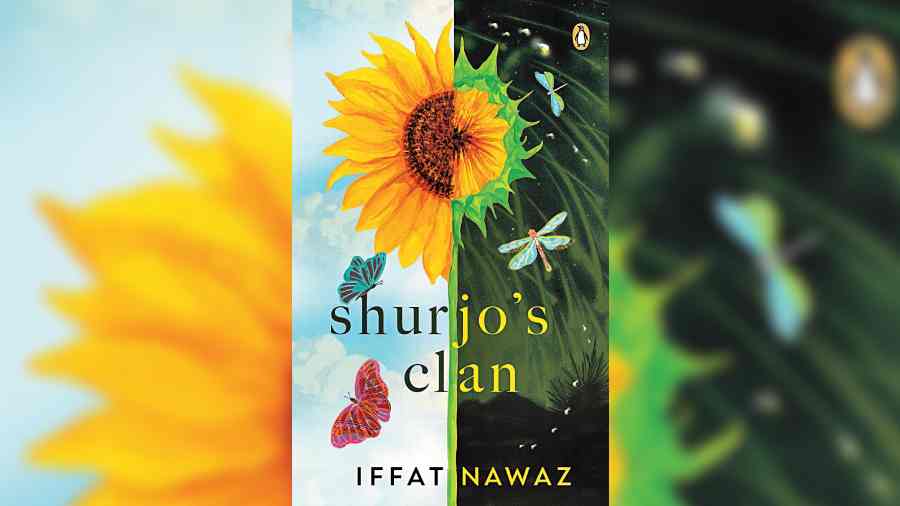

Shurjo is short for Shurjomukhi, who is the protagonist of my novel Shurjo’s Clan. Shurjo means sun in Bengali and Shurjomukhi is sunflower. When I first started writing the book the substance was quite different from what it is now — it was longer, darker and heavier, much like how war and migration stories often are. But after writing the first draft I realised I wanted to talk about displacement, identity, inherited grief but in a way where all such dense matters are turned towards light and that’s when Shurjo emerged. Changing the name of the protagonist also worked as a constant reminder for me to simplify the intensity and obscurity, and not dig down towards the abyss but look up to the sun.

Lastly, I must mention the influence of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother while writing Shurjo’s Clan. They have written about atavism and how we must heal the weight of heavy pasts by offering it to the eternal light — hence… Shurjo, Savitri, that which is of the Sun.

This is your debut novel, what inspired you to pen a historic magic realism theme?

I think many of us live through our days stepping in and out of magic realism. It adds more interesting layers and symbolisms to our otherwise mundane lives. Much like the protagonist of Shurjo’s Clan, Shurjomukhi, aka Shurjo, I was also born into a family of freedom fighters and martyrs. Their photos hung at my childhood home and their tales were half-hidden, half-told and half-gathered. There was a lot of mystery around in those years after the war, and the presence of those who passed during the partition of India-Pakistan and then the 1971 liberation war of Bangladesh lingered in our lands. It was easiest for me to decipher the vividness of these subtle shadows when I wrote using magic realism. It made more sense to me as well when I understood it that way. I strongly felt that the ones who came before me, the ones I did not ever meet in person formed the premise of this book and I crafted it from the feelings which arose while connecting with them.

How did the history of Bangladesh influence your novel? Did you want to talk about any untold truths?

Those of us who are born during the first decade of liberated Bangladesh inherited the leftover, secondhand trauma of the war; the oral and written history of the new nation was something our childhood was deeply steeped in as well. From a very young age, our parents wanted to ensure we knew how Bangladesh was born and what the cost of their sacrifices were. We were handed books on the war including personal memories of the survivors — this all happened at an age when we probably should not have read such books or seen such images. But we did and they had a profound effect on us. As for untold truths, perhaps this is it, this way of being raised, this heavy inheritance of memories of our forefathers and how we have processed them and are still healing from it. Also, very few narratives exist about the folks who moved to East Bengal from West. My family is one such one and there are many others — I think these families did not want to differentiate themselves in their new homes and wanted to lessen their otherness by suffocating large parts of their pasts. As a result, many of their narratives got lost. I tried to bring a bit of it in Shurjo’s Clan.

Since this is a story of Partition how did your novel voice unity?

Shurjo’s Clan is not necessarily only a story of Partition, however, 1947 has its role in it. And the novel does not work from the standpoint of division but rather the similitude that we all carry, how forced new identities can often become a burden, and how tough finding new ways of belonging can be. Also, none of the characters of Shurjo’s Clan are rooted in any specific religion, I have also tried my best to stay away from any superficial labels which create avoidable boundaries.

Do you have any writers you look up to, since there are so many authors who have written about partition?

I admire the work of Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Pablo Neruda. Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five also moved me quite a lot, which is semi-autobiographical, humorous, sad yet about anti-war.

Could you please share with us an excerpt from one of your favourite parts from your book....

Here is an excerpt from Chapter 4 which is titled Misunderstood Reflections, describing Shrujo’s maternal grandparents’ first months in Dacca after migrating from Murshidabad.

“The day Mehul took Shantori to see the Buriganga, Dacca’s swampy weather was at its height. Many bodies carried seasonal fevers. The air hung heavy, and the mosquitos and flies needed little effort to stay afloat. By the time they reached the river, the sun was already hiding. The sky wore clouds like butter smeared on toast, too grey-white to allow any clear reflection to be cast on the river. Shantori stared at the grim waves.”

This is one of the excerpts that I hold close to my heart.

What would you like to tell your readers who are new to this theme?

I want to bring familiarity to this theme of inherited grief and trauma as, unfortunately, our world is still grappling with issues of migration, displacement and identity. I would like to tell my readers that we can rewrite and re-think the way we look at these incidents, that we should question what we have been told as children, we should re-examine the biases we have grown up with and, most of all, we should clear our insides of the darkness we are unknowingly carrying forward, the grief we move with, the grief which is dressed as our family’s or nation’s honour. I believe we can honour our history better by healing from its pain, with compassion leaping into something lighter and brighter. I also hope young adults, teenagers, university-going students will pick up Shurjo’s Clan.

I feel our generation has not done the best job of creating a bridge with the youth. There is a need of clarity in the way we express emotions, and the strength of our best-realised feelings need to be transferred to this future generation. It will be fantastic if young people resonate with this book, and I would love to have dialogues around the issues woven through Shurjo’s Clan with them; I am eager to learn new perspectives from the youth as well.

Are you working on a new project? What can we expect from your desk?

I am working on a novel whose working title is ‘Easy Love’. It is on magic realism and set in a tiny city by a sea where nine characters come together from different walks of life to find the ingredients of effortless love. It is inspired by a line from Rabindranath Tagore’s novel Noshtoneer, “Sohoj sukh, sohoj noi”, which means, ‘Simple contentment is not simply attained.’