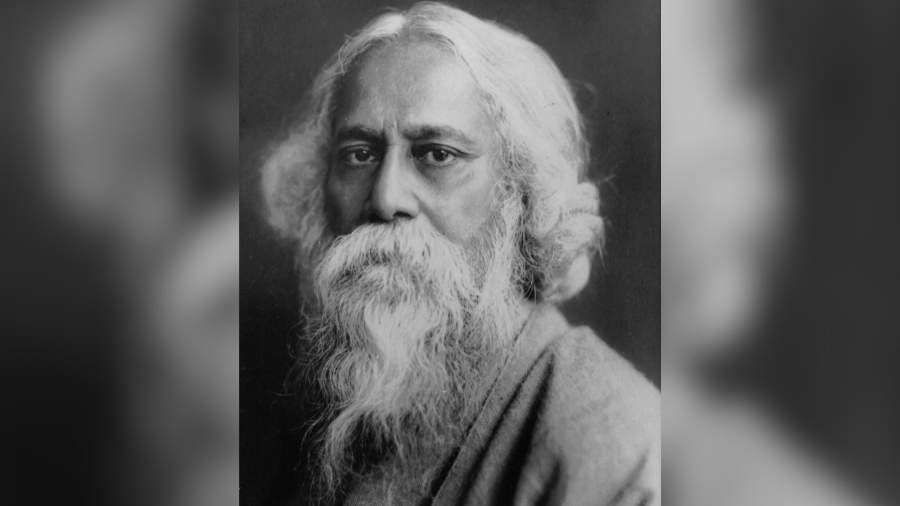

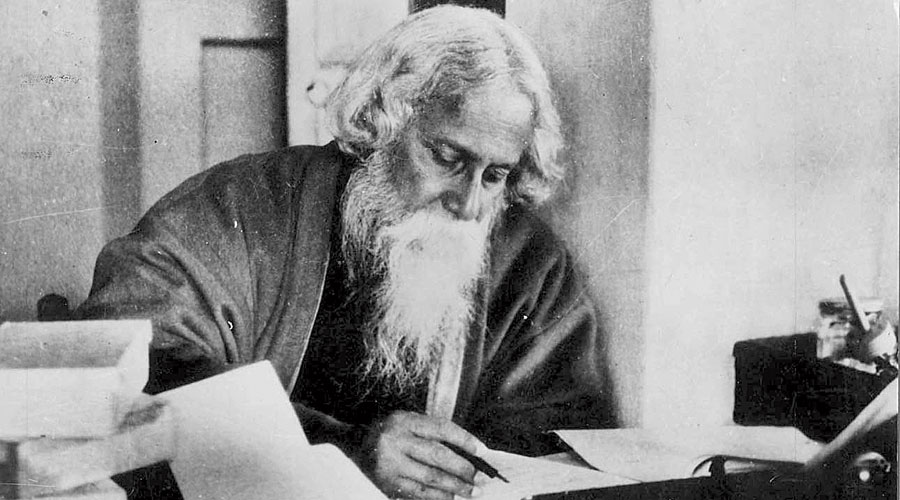

Rabindranath Tagore has now been dead for longer than he was alive. And yet, within the confines of the average Bengali household, Kabiguru lives on, his presence growing more luminous by the day. Soon enough, Bengal will run out of people who met or knew Tagore personally. But it seems impossible that Tagore will ever be a stranger to Bengalis, for whom their language, identity and culture are inseparably interlinked to a man who did not spend a single day in independent India.

What is it about Tagore that casts a permanent spell over Bengalis? Every community has its heroes, icons and legends, but the passion that Bengalis have for Tagore (passed on like an heirloom) is virtually unparalleled. To this day, Bengali literature, music and art are not just incomplete without Tagore, but are circumscribed by him. Author and critic Amit Chaudhuri summed it up succinctly when he said: “Tagore was a historical pinnacle (for Bengalis), after which everything was a kind of a decline.” There is no doubt that Tagore remains one of modern India’s finest artists and thinkers and also one of the few Bengali polymaths of the last two centuries. However, the unstinting adoration that Bengalis shower on him and his work, to the point where objective critiques are both few and futile, raises a simple but vital question — why are Bengalis endlessly obsessed with Rabindranath Tagore?

Simplifying a genius for cultural capital

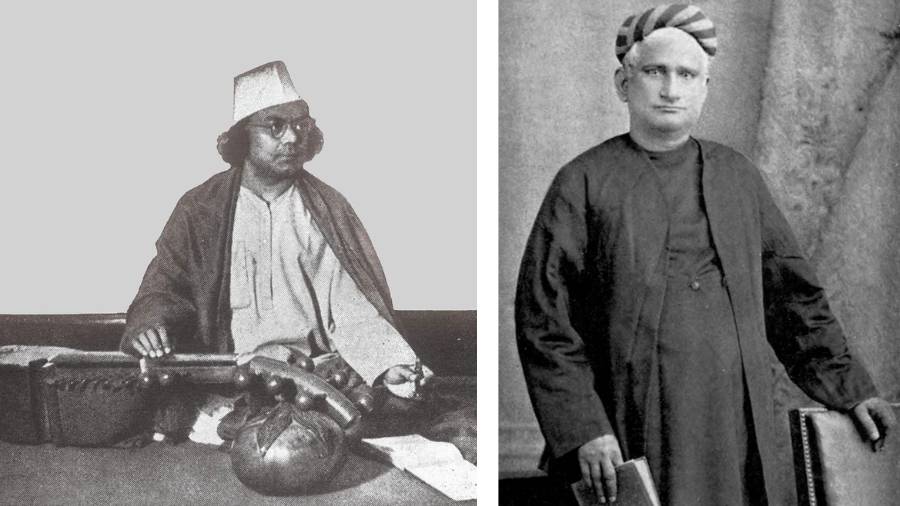

Every genius is a product of their context. Tagore was no different. In the absence of his syncretic and privileged family, which he himself described as a “confluence of three cultures: Hindu, Mohammedan and British”, Tagore may not have been an artist at all, let alone the greatest Bengalis claim to possess. But what cemented Tagore’s status among Bengalis also had a lot to do with timing. Unlike Satyajit Ray, who had Mrinal Sen, Tagore never had a direct contemporary from Bengal who could feasibly rival his range or his reputation. The other stalwarts of Bengali arts and culture, from Raja Ram Mohan Roy to Michael Madhusudan Dutt, from Bankim Chandra Chatterjee to Kazi Nazrul Islam, came either before or after Tagore’s peak years (in terms of productivity) and were not subject to constant parallels or comparisons with the Nobel laureate. Even those whose careers coincided roughly with Tagore’s, such as Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, proved too esoteric in their influence in front of Tagore’s sheer breadth of output.

This apparent limitlessness of Tagore’s output also made him the right sort of luminary for posterity, for no better reason than the fact that his creations became conveniently capacious. Take, for instance, Rabindrasangeet, without which no Bengali cultural programme can be staged, even in 2023. With more than 2,000 original compositions, Tagore’s collection of songs is so vast and eclectic that it has long stopped mattering how they emerged or what they signified. Layered with paradox and ambiguity, the deeper meaning of Tagore’s songs, many of which were inspired as much by Scottish and Irish styles as by Indian classical or folk music, is no longer relevant. This is why Amra Sobai Raja can double up as a prompt for musical chairs at childrens’ birthday parties as easily as it can be used for college dramas that champion democracy. An even more pertinent example is Ekla Cholo Re, which is best remembered by today’s youth as the defining soundtrack of a pregnant woman’s search for her husband and vengeance, but which, in reality, was one of Tagore’ most politically powerful anthems.

Stalwarts of Bengali art and culture like (left) Kazi Nazrul Islam and (right) Bankim Chandra Chatterjee came either before or after Tagore’s peak productive years and were not subject to comparisons with the poet Wikimedia Commons

In other words, Bengalis invariably find what they look for in Tagore, even if Tagore rarely saw those same things himself. This leads to the birth of the so-called Rabindrik outlook on life, wherein quintessential Bengali middle-class virtues such as musicality, discourse, even languor are fetishised as inevitable components of amader culture (our culture), with the ultimate seal of approval coming from Tagore’s appropriated and sometimes misunderstood legacy. The next step for such an outlook is to spawn a milquetoast mixture of art and aesthetics (revolving around Tagore’s oeuvre) that converts a great creator into a timeless template, to be seamlessly retrofitted for respectability and repeatability, generation after generation. In essence, it means the simplification of genius for cultural capital. Although Bengalis would like to believe it means them frequently renewing their special relationship with Tagore.

The forgotten aspects of Tagore

A scene showing Tagore (played by Victor Banerjee) and Victoria Ocampo (played by Eleonora Wexler) from the 2017 film ‘Thinking of Him’ TT Archives

For a people that can never get enough of Tagore anecdotes and memorabilia, Bengalis pay little to no attention to some of the most fundamental aspects of Tagore. First, Tagore, the philosopher, whose faith in universal fraternity as a counterpoint to narrow and divisive nationalism has been largely overlooked for decades. In the contemporary political climate, when nationalism has emerged as a hot-button issue, Bengalis seem least interested in reminding their fellow Indians of how Tagore believed that “patriotism (used interchangeably with nationalism here) cannot be our final spiritual shelter, [for] my refuge is humanity”. In reams of letters to and from Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (compiled and analysed in Rudrangshu Mukherjee’s Tagore and Gandhi), Tagore makes the case for a harmonious balance between internationalism and patriotism that all of us could do with exploring, if not embracing, today.

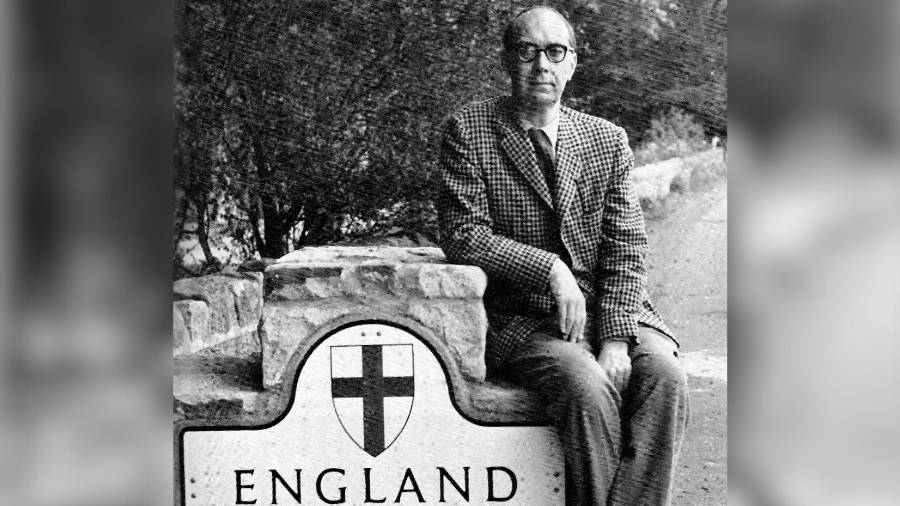

Second comes Tagore, the caricatured mystic, whose magnetic hold over Bengal initially found massive resonance, and then, almost as much ridicule across much of the rest of the world. Following his acceptance of the Nobel Prize in Literature for Gitanjali in 1913, Tagore rocketed to fame as Germany’s first best-selling author, was hailed as a cult-figure in Spain, and accumulated considerable renown in Russia, Japan, Latin America as well as the US. However, within a few frivolous years, Tagore’s global standing diminished considerably, with the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges calling him a “hoaxer of good faith… a Swedish invention”. In the UK, where Tagore’s translations into English had once won over the likes of William Butler Yeats and Ezra Pound, Tagore was quickly reduced to an Oriental sage whose literature (along with his beard) evoked more amusement than admiration. When asked what he thought of Tagore, Philip Larkin, dubbed “England’s other Poet Laureate”, said: “F*ck all.” For all the emotions Bengalis feel for Tagore, there has been no concerted effort on their part to rehabilitate Tagore’s image overseas, perhaps because he is adored too much within the Bengali community to be made accessible to others.

Philip Larkin Flickr

Third, Tagore, the lover, which immediately springs to mind Tagore’s beautifully blurry equation with Kadambari Devi, a favourite topic of gossip during Bengali addas. But the truth is that his sister-in-law was one of many women Tagore had profound liaisons with. Notable among them was Argentine intellectual Victoria Ocampo, 29 years his junior, with whom Tagore definitely had a spiritual connection, if not a sexual one (their relationship was fictionalised on screen in Thinking of Him, released in 2017). In her autobiography, Ocampo narrates an incident involving Tagore (which has been debated and discredited by others) that most Bengalis would have a hard time imagining, let alone recalling:

One afternoon, as I came into his (Tagore’s) room while he was writing, I leaned towards the page, which was on the table. Without lifting his head towards me, he stretched his arm, and in the same way as one gets hold of a fruit on a branch, he placed his hand on one of my breasts. I felt a kind of shudder of withdrawal, like a horse whom his master strokes when he is not expecting it. The animal cried at once within me. Another person who lives inside me warned the animal, “be calm… fool”. It is just a gesture of pagan tenderness. The hand left the branch after that almost incorporeal caress. But he never did it again. Every day he kissed me on the forehead or the cheek and took one of my arms, saying “such cool arms”.

Moving on from Tagore

If and when Bengalis move on from Tagore, they may be able to better understand who he was rather than who he has been made into posthumously TT Archives

Growing up in Kolkata, I rarely encountered people making much of a fuss over Gandhi Jayanti. The birth anniversary of Subhas Chandra Bose would also pass rather quietly. For many years until the government reminded us, most of us had no idea when exactly Swami Vivekananda was born. But Rabindra Jayanti was different, a red-letter day that provoked more pre-event practice than exams and more post-event commentary than results. This continues to be the case today, with Tagore’s birthday celebrations stretching over days, sometimes weeks, with just about every Bengali with resources or enthusiasm (sometimes too much of both) intent on remembering Tagore in some way, shape or form. Increasingly, Tagore mania is taking over Bengali diasporas, too, with the euphoria and excitement second only to Durga Puja.

All this begs an obvious question— why do Bengalis need to move on from Tagore? What is the harm in celebrating a man who has given so much to so many for so long? Why not indulge in a single individual’s excellence, even if it breeds collective complacency? The answer is that Bengalis do not have to move on from Tagore, and they probably never will. But if and when they do, they will not stop consuming Tagore. Instead, they will start engaging with him as a man of flesh and blood, whose works were as much a product of their time as of their creator’s talent. The obsession with Tagore will then give way to a form of scrutiny that is more interested in understanding who Tagore was, complete with his failings and prejudices, rather than the infallible icon he has been made into posthumously.

Such a time and space will allow Bengalis to disagree with Tagore’s cherished ideals (both real and imagined), even dislike them, just as many Bengalis gradually feel more comfortable expressing their disapproval about fish, football and traditional fashion. This would open up avenues to a recalibration of Tagore that is less romantic and more realistic, one that reveals him more than it reveres him.