The first time he saw him, tall, slim, long strides loping soundless towards the crease, he couldn't take his eyes off him for fear that he might never see such menacing beauty again on a cricket field.

No wonder the umpires would name Michael Holding ‘Whispering Death’.

With Vivian Richards it was different. There was something regal about his unhurried saunter to the wicket, the way he would look around the field, as a king would survey his court, knowing full well that in this realm there was only one monarch. And that was him.

If Richards was the monarch, Brian Lara was the poet-prince who rewrote cricket’s epic.

St John’s, Antigua. April 12, 2004. By the time he was done, Lara had compiled — in true Miltonian manner — a never-before 400 not out. It was cricket’s version of paradise regained. And of transcendence in an imperious backlift.

If Viv Richards was the monarch, Brian Lara was the poet-prince who rewrote cricket’s epic Julian Herbert/ALLSPORT

But don’t bother, if you aren’t a West Indian at heart — because this hurts. As the squandering of a high legacy hurts even those not directly affected. Also the incongruity of it: a cricket World Cup without the West Indies.

Maybe that’s why every cricket lover should bother, especially those who grew up in an age when cricket and the Caribbean were still synonymous. True, they loved to read about W.G. Grace and Don Bradman, too; about Douglas Jardine and Bodyline; of Bill ‘Tiger’ O’Reilly and Fred ‘The Demon Bowler’ Spofforth; about how the Ashes came to be called the Ashes, but those names and nomenclatures had been handed down with conditions, courtesy of records and stories of fierce contests. The West Indies were different; not that they lacked aggression or even rebuffed the allure of statistics. It was all about the brand of cricket they played — pure, uninhibited and utterly captivating.

Now, for the first time in nearly half a century since 1975, when the first ODI World Cup was played, the once all-conquering West Indies wouldn’t be there on cricket’s biggest stage, beaten by minnows Zimbabwe, the Netherlands and then finally by Scotland.

“This is probably one of the lowest points I’ve had with the team,” all-rounder Jason Holder would say after the July 1 loss to Scotland, which meant the West Indies wouldn’t be travelling to India for the one-day international tournament later this year.

Kyle Mayers of West Indies is bowled by Chris Sole of Scotland during the ICC Men's Cricket World Cup Qualifiers ICC

From a cricketing point of view, this is tragedy, a fall from grace that reminds one of certain aspects of Greek tragedy. Not merely the tragedy of absence from an arena they once dominated but also in the fall of a heroic idea.

The West Indies were once that idea, invincible on the field of play and irrepressibly romantic. It was this same idea that gave the game players like George Headley, Learie Constantine, Frank Worrell, who transformed the diverse Caribbean islands into a united West Indian cricketing identity; Clyde Walcott, Everton Weekes, Rohan Kanhai and Wes Hall. And, of course, the finest of them all, Garfield Sobers. An irresistible band of men whose play was an exhilarating mix of Dionysian frenzy and Apollonian elegance — a fusion that was both raw and beautiful, and infinitely seductive.

Cricket was their deliverance; in beating the ‘superior’ white man at their own game lay the black man’s redemption. In the popular imagination, especially in cricket-playing parts of the colonised world, the triumphs of West Indian teams of those early days belonged to the league of Jesse Owens’s extraordinary feats in Berlin in 1936.

This is thus a story for every cricket lover, whatever their individual country loyalties, because of the tragedy of it. The one that has befallen King Richards’s cricketing compatriots.

And it hurts — much more than how Holding and Andy Roberts had hurt Tony Greig’s England in the summer of 1976.

Error of judgement

There had probably never been a fall so far-reaching in its impact, though none would have known it then.

In a way, July 1 of 2023 was the inevitable denouement since Clive Lloyd’s team of outrageously capable men relinquished their supremacy — and what would have been their third successive cup of triumph — in a moment of unmatchable hubris. That was forty years ago, almost to the week.

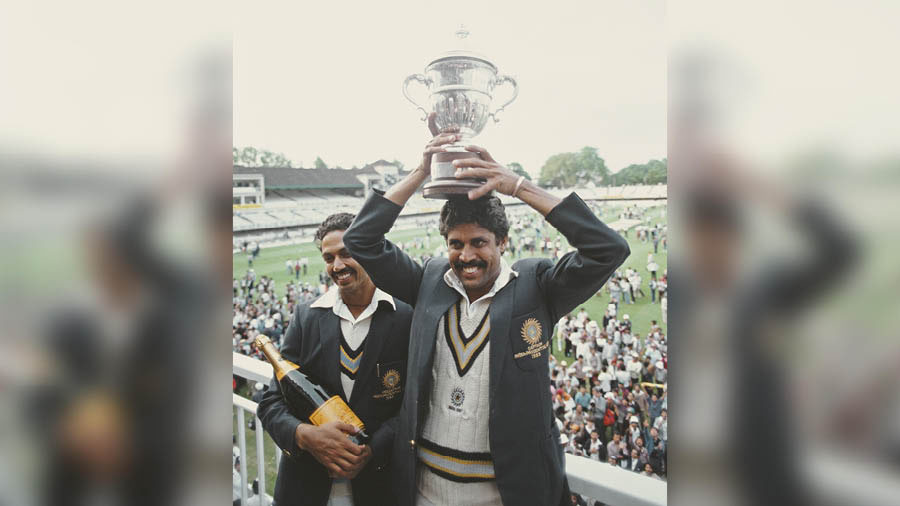

Lord’s, June 25. The final of the 1983 World Cup. Favourites West Indies versus underdogs India. Madan Lal, medium quick but possessed of the soul of a fighter, leaps high, the burden of hopelessness and impending defeat heavy on his shoulders.

At the other end of the wicket waits Richards, 33 off 27 balls, as if in a rush to finish things off before the chewing gum in his jaws — the flavoured subplot to the story of Viv the Destroyer — lost its sweetness.

Seven boundaries had already rasped off his blade. The king was in an imperious mood that day, regally, spectacularly ominous; each stroke of his cleaving deeper into the heart of every Indian watching the game on television.

Ball number 28 had seemed innocuous. What happened next has probably been watched millions of times on YouTube. Richards had looked to step out but changed his mind at the last moment. Kapil Dev, running backwards, eyes always on the ball, would cling on to the miscued gift. Richards, cricket’s undisputed king, as dominant as they come, had erred in judgement and his miscalculation would lead to instant karma. Ecstasy for India; doom for the West Indies.

Now hearken back to what the old masters had said: misfortune not brought about by villainy but by “error of judgement” (hamartia). In other words, a fatal mistake that leads to downfall. That’s how the ancient Greeks defined the term.

Remember Icarus? His wings of wax melted, the sea rushing up from below as he hurtled down from the sky, bereft of the air’s buoyancy. The fabled high-flyer from Greek mythology had flown too close to the sun in a moment of foolhardy daring that an older man, his father, inventor and master architect Daedalus, had warned against. While it was Richards’s moment of indiscretion that started the rout that June day, forty years ago, the West Indies were guilty of collective failure. And of collective overconfidence, or hubris.

For India, that day would set the stage for their future ascent as a cricketing powerhouse. For the West Indies it would be what Aristotle had defined as peripeteia, or a sudden reversal in fortunes — shades of Greek tragedy here too — though the lasting impact wouldn’t be immediately apparent.

For India, that day in 1983 would set the stage for their future ascent as a cricketing powerhouse. For the West Indies it would be what Aristotle had defined as peripeteia, or a sudden reversal in fortunes — though the lasting impact wouldn’t be immediately apparent Adrian Murrell/Allsport//Getty Images

The West Indies would hit back with vengeance when they toured India that winter and continue their domination of the game for some more years. Richards was still in his prime. Among the fast men, Colin Croft had retired, so would Roberts, but Holding and Joel Garner would be around for a few more years. But their grip would gradually loosen through the 1990s, as Richards, Gordon Greenidge, Desmond Haynes, Jeffrey Dujon and Malcolm Marshall retired, though moments of sublime exuberance or breathtaking mayhem would light up the field every now and then. Such as Lara’s Test match-winning 153 not out against Australia in Bridgetown in 1999; Carl Hooper’s 105 against South Africa in an ODI at Lahore in 1997; Courtney Walsh’s 4 for 16 against Pakistan in an ODI at Cape Town in 1993; and Curtly Ambrose’s incredible 7-for-1 Test match-winning spell at Perth the same year.

England too wouldn’t have fond memories of Ambrose, undone by the 6ft-7in wiry pacer’s 8/45 in 1990 in Bridgetown.

Did anybody ever figure out the Antiguan? The closest they got was to a differential. Thin versus Ambrose thin.

Collapse of imagination

This was the imagination that still stayed with cricket lovers even well after 1983. And the believer, still mesmerised by the memory of Holding’s long-legged run, kept his faith. “Come on, man,” he would say, hand around your shoulder, “there’s always something to look forward to.” But the West Indies would never win the ODI World Cup again.

Now, with their exit from the 2023 World Cup, that imagination has collapsed. It’s taken a long time to come, this day. After years of desultory play, of endless defeats and occasional victory. Of emphatic, hope-stirring, singular brilliance, squandered in collective failure. So distant from those heady eighties that fact might have passed off as fiction were it not for memory. Off the 50-odd Test series the West Indies have played since the last of the greats — Lara, Ambrose and Courtney Walsh — moved on, they have won barely a handful. Most of them against the lesser teams. And, to be honest, it could well have been India-2, West Indies-0 earlier this week, had the rain not intervened.

Off the 50-odd Test series the West Indies have played since the last of the greats — Lara, (R) Curtly Ambrose and (L) Courtney Walsh — moved on, they have won barely a handful Michael Dodge/Getty Images

Even the two T20 World Cup victories — in 2012 and 2016 — proved to be a false dawn for Caribbean cricket. The architects of those triumphs would have long and lucrative careers with T20 franchises across the world but the lot of West Indian cricket did not change. In last year’s T20 World Cup, the West Indies finished bottom of the group, after losing to Scotland and Ireland.

Former fast bowler Ian Bishop felt the decline has been gradual, for about a decade or so. “[I]t is a stifling reality of where the [West Indian] cricket is at the moment,” Bishop, one of the last of the Caribbean greats, told ESPNcricinfo after the July 1 match.

The signs were all there for quite some time. Faulty preparations, lack of resilience, slow erosion of talent, lack of leadership and coordination, and failure to catch up with the pressures of an evolving game. Again, shades of Greek tragedy. The protagonists blunder, but the reverberations are far out of proportion to the flaw, the catastrophe compounded by chance and other external forces.

“I just hope that we can build from here,” Bishop said. “They say it’s only cricket. But cricket has a significant impact on Caribbean identity around the world.”

Can the West Indies ever turn around and re-emerge from the shadows they have been relegated to? Only time will tell iStock

In his post-match conference, Holder stressed on the need for working together.

“It’s [cricket] not an individual thing or a territorial thing. We’ve got to come together as a region... and really, really think about how we want to go forward as a group and make it happen,” he said.

“It’s not a quick-fix, it’s something we need to spend time on. As I said, development [at the grassroots] is the most important thing, where we can just put things in place and develop our talent. Hopefully, in the next couple of years we can see the fruits of that crop.”

Can the West Indies ever turn around and re-emerge from the shadows they have been relegated to? Only time would tell. Till that happens, this would hurt. And badly.

But even tragedies pass. And it can’t get any worse than this.