Club three different generations of Bengalis in a single room and even though you may not succeed in getting them to agree on much else, they will inevitably find common ground when the conversation turns to their childhood.

That is because growing up in a Bengali household comes with its own distinct set of experiences, which are carefully passed down from generation to generation, much like long-preserved family heirlooms.

And while Bengalis may never be able to settle their ilish vs. chingri debate, they will all unanimously agree that the only breakfast befitting a Sunday morning is a plate full of phulko luchi and aloor torkari.

My Kolkata takes a look at some of these shared experiences, centred around growing up in a true-blue Bong family.

Those nicknames (who even comes up with them?)

A Bengali’s love for nicknames is almost as famous as their love for politics and football. Each child in the family has a specially designated daak naam, which is sometimes given to them even before they have an actual name. And we had made our peace with it, as long as it was limited to the generic babu, shonai and tatai.

But imagine being the youngest sibling in the house only to be called buro (old), simply because you liked playing with your grandfather’s cane!

Yikes! Now that’s a name your friends will never forget.

The season of everything new

Once a year, in the month leading up to Durga Puja, Bengali families go on a shopping spree. And this is not just limited to new clothes and shoes. Instead, it expands into new curtains, new bedsheets, new table cloths and almost anything else in the house that needs changing.

And come Durga Puja, both the house and its members are decked up in all things new and shiny. For the rest of the year, any other big buys are added to that imaginary list titled ‘Ekebare pujor shomoy kinbo’, meaning ‘Add it to to the Puja shopping list’.

It is an annual makeover for us (and everything around us).

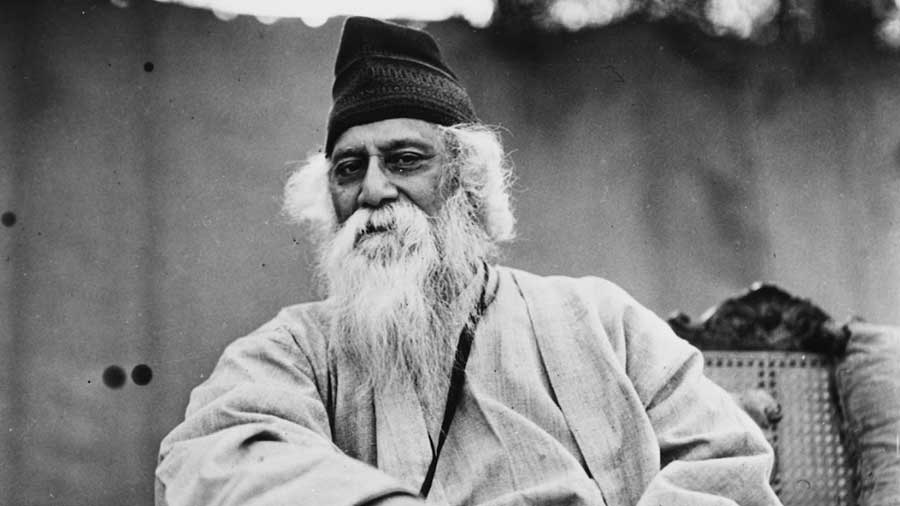

Our first ‘thakur’ is ‘Robi Thakur’

Before a Bengali kid has had the chance to even understand the notion of a god (called thakur, in Bengali), they are introduced to a thakur of a very different kind – Rabindranath ‘Thakur’. Spelled ‘Tagore’ in English, the correct Bengali pronunciation of the word becomes a homophone with the term used to refer to god.

And growing up in a Bengali family means appreciating Rabindranath Tagore’s works in all its vastness. This acquaintance begins with Sahaj Path – a learning book of the Bengali alphabet written by Tagore – and keeps growing over the years, with his stories, poems, novels and of course his music, known as Rabindrasangeet.

Getty Images

In fact, the birth and death anniversaries of Tagore – called Pochishe Boisakh and Baishe Srabon respectively – will almost always see commemoration in most Bengali households, with every member of the family participating in something or the other, be it singing, dancing or recitation.

The Holy Trinity of classes

If you thought that schools overdo their emphasis on extracurricular activities, wait until you meet Bengali parents.

Each Bengali kid, at some point in their lives, have found themselves attending either a dance class, or a drawing class, or a singing class (or maybe even all three). Together, these three classes form the Holy Trinity of extracurricular activities that all Bengali children find themselves routinely subjected to.

And make no mistake, each of these classes come with their fair share of homework and exams.

As if we didn’t already have enough of those!

The things we say

There are certain catchphrases that are typical of a Bengali household. For instance, naughty kids in the house might be sternly warned to stop their bandramo (monkeying around) when guests come over. Or, a particularly rebellious teenager’s protests might be greeted with “Tor Barota Beje Geche”, meaning “You have been spoiled beyond repair”.

Sometimes, when confronted with an unjust demand, a Bengali mother might exclaim at the audacity of this “Mamar barir abdar” — referring to the pampering that one receives when they are at their uncle’s (read: relative’s) house. For example, asking for a breakfast of luchi and aloor torkari on any other day of the week apart from Sunday, is most definitely “Mamar barir abdar”.

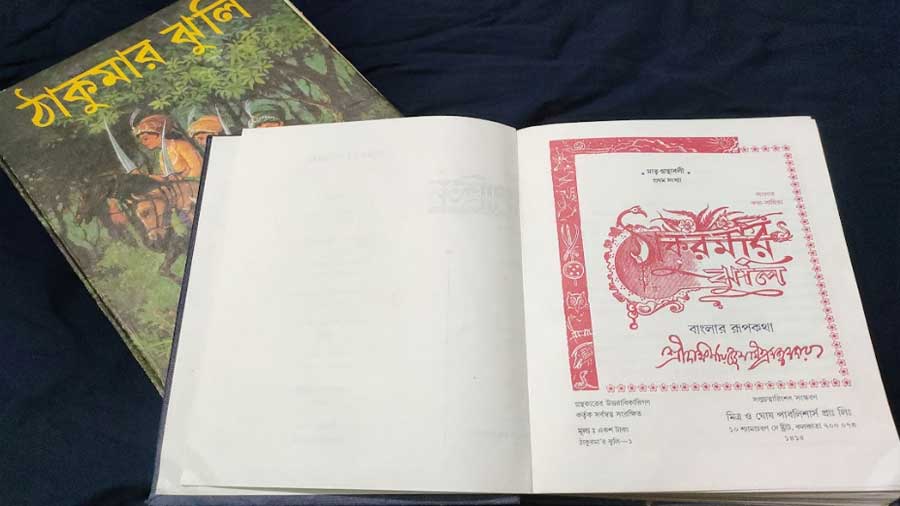

That one grandmother with her ‘jhuli’

All Bengali kids have one universal grandmother, and she comes with a big bag of stories. A collection of folk and fairy tales from Bengal’s villages, the phrase Thakurmar Jhuli means Grandmother’s Bag of stories, and was written by author Dakshinaranjan Mitra Majumdar back in 1907.

Since then, the book has clinched a permanent spot for itself on bookshelves across Bengali households. Filled with stories about supernatural entities like bhoots and petnis, these stories continue to capture the imagination of children even today. Such is their popularity, that they have also been made into cartoons for young viewers.

So, the next time you’re visiting your bong friend, make sure you ask them to fish out their copy (or copies) of Thakurmar Jhuli and translate a few of those stories for you.

The day of no studies

Did you know that Bengali kids have two stipulated days in the year, when they are not expected to even touch their books, let alone study?

Every year, during Saraswati Puja, children in Bengali families gather all their school and college books, which are then kept near the feet of the goddess’ idol. Since Saraswati is hailed as being the Goddess of Wisdom, it is considered auspicious to have your books blessed during the puja rituals. And with no books to study from, the children are left free to go about doing what they please all throughout the day!

We believe in beauty sleep

Bengalis love their afternoon siesta so much that they even gave it a special name – bhaat ghum! Since bhaat (rice) is a staple for lunch across Bengali families, the term bhaat ghum refers to the nap that one takes after lunchtime.

Usually, it is normal to feel a little sleepy after having a heavy meal. But instead of working through that spell of drowsiness, Bengalis indulge in the delight of simply surrendering to that feeling. And more often than not, will do anything to avoid giving up their beloved bhaat ghum.

A Bengali’s best friend

There is no such thing as magic. However, there is something called Boroline. And no matter what the problem, you can be sure that the solution is always Boroline!

This antiseptic cream can be told apart by its distinct texture, scent and packaging. Launched first in 1929, it has eventually grown to become a Bengali family’s constant companion. Even now, despite the growing popularity of other over-the-counter antiseptic creams, Boroline continues to reign supreme.

Fell down and scraped your knee? Boroline will take care of it.

Dry skin? Ditch that moisturiser for some good ol’ Boroline.

Packing for a trip? Boroline first, clothes later!

That OG winter gear

Irrespective of whether the cold has actually set in yet or not, at the slightest hint of a chill in the air, Bengali parents will bring out every kid’s worst winter nightmare – monkey caps.

TT Archives

This ridiculous looking headgear draws incessant complaints, whining and even crying. But despite all that, you will find children being bundled off to school in sweaters and monkey caps during those cold winter mornings. And you can buy those fancy fleece and woollen caps all you want, but nothing impresses Bengali parents more than a kid who puts on their fashion disaster of a monkey cap without any protests. (They are our version of Sharma ji ka beta!)