Large iron-shod wooden wheels, rubber engulfed seat on a wooden plank, and a tarpaulin shelter amalgamate into a vehicle that has navigated the narrow lanes of Kolkata since British rule — the humble, hand-pulled rickshaw.

A human-powered mode of transport, the hand-pulled rickshaw was introduced by the British in India in the 19th century. Originating in Shimla, it was brought to Kolkata by Chinese refugees who were seeking asylum in the country due to political unrest in China. Slowly but surely, the rickshaw became the predominant mode of transportation in Kolkata, then the British capital of India, and provided employment to refugees as well as thousands of migrants that came from impoverished rural areas.

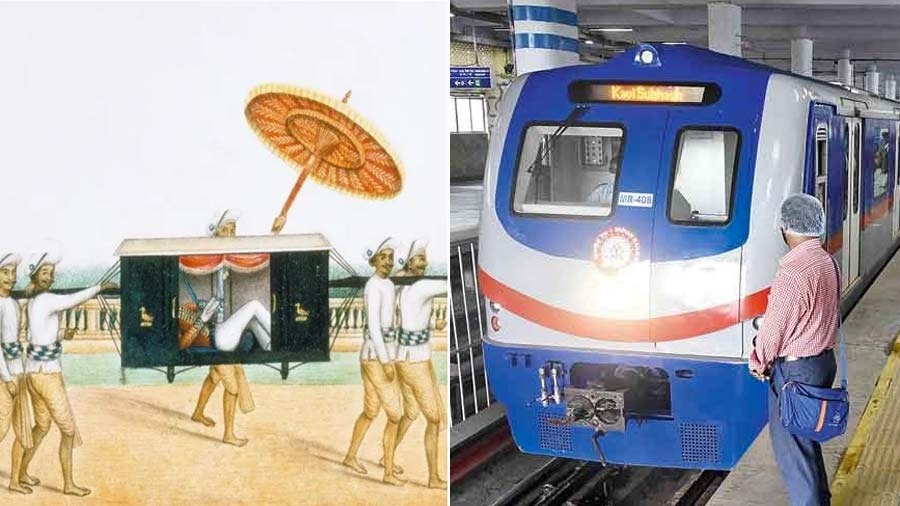

The hand-pulled rickshaw reinforced the imperialistic dynamic between master and slave

Even though the rickshaw acted as an agent for the reinforcement of colonial hierarchy, it manoeuvred through the City of Joy for about 70 years after the end of the British rule in 1947 Shutterstock

The vehicle became a popular medium of commute, particularly among the rising middle-class, many of whom used it as a means to showcase their socio-economic status. At the same time, the hand-pulled rickshaw also reinforced the imperialistic dynamic between master and slave. The structural design of the rickshaw accentuated this image of hierarchy, where the poor man laboriously pulled the luxuriously seated passenger.

Even though the rickshaw acted as an agent for the reinforcement of colonial hierarchy, it manoeuvred through the City of Joy for about 70 years after the end of the British rule in 1947. The continuance of the hand-pulled rickshaw indicated practicality, particularly for the common masses. The vehicle’s compact size, affordability, non-reliance on fossil fuels and ability to navigate the narrow lanes of Kolkata, even in heavy monsoon, contributed to its sustenance in the city for close to three generations.

Rapid industrialisation, however, did not allow the hand-pulled rickshaw to retain its wooden wheels. The vehicle’s utility started diminishing as independent India started moving towards becoming a fast-paced, globalised nation in the 21st century. In an economy that paid and deducted wages based on the worker’s hours, the working class preferred using transport that helped them commute to their workplace faster. With this increasing commodification of time, rickshaws seemed rather sluggish, and the masses shifted towards using swift-moving cars, buses and autorickshaws for commuting. Hand-pulled rickshaws, with their slow pace, were pulling the riders down on the socio-economic ladder. While rickshaws came to be associated with the anglicised city of Calcutta and its poor, slow growth rate, the fast-paced and mechanised modes of transport symbolised wealth and prosperity in the rechristened Kolkata. Automobiles, particularly cars, became the new symbol of socio-economic status, with metal and alloy wheels becoming the delegates of development for the city.

‘Why would I pay to be manually pulled by a poor or old man (or both) when I know it’s wrong?’

Many passengers feel that sitting in a hand-pulled rickshaw is immoral Amit Datta

Sonal Joshi, a 48-year-old homemaker residing in Kankurgachhi, had often used the rickshaw for commuting to the local market when she lived near Burrabazar, one of the main shopping districts of the city. She said that she does not see a lot of rickshaws anymore: “They’re found in pockets, that too in the old city. The last time I took a ride on the rickshaw was about 10 years ago.” When asked how she would feel riding a rickshaw now, she added: “It seems inhumane. Now when I think about being pulled by another human, especially someone old, it’s saddening. Why would I pay to be manually pulled by a poor or old man (or both) when I know it’s wrong? We all know that rickshaws are very slow to ride, but I think people also don’t want to sit in the rickshaw because they have realised how immoral it is."

In 2005, the then chief minister of West Bengal, Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, vowed to “banish the hand-pulled rickshaws from the city (Kolkata) within the next three-four months”. He said that the “sight of a human pulling another human on his shoulder for a living doesn’t enhance Kolkata’s image”. There have been various attempts by government authorities before and after to get the rickshaw withdrawn from the streets. For instance, Jyoti Basu, the chief minister between 1977 and 2000, made attempts for the withdrawal of hand-pulled rickshaws from Kolkata but was unsuccessful due to political unrest.

With successive governments aiming to attract foreign investment to Kolkata for the expansion of industrialisation and economic liberalisation, the rickshaw began to be correlated with an “undeveloped” image of the city.

This meant that the rickshaw, even though it formed the livelihood for thousands of migrant workers, did not fit in with the register of the government and was viewed through black and white lenses. Officials were adamant on implementing development policies borrowed from capitalistic practices that ultimately led to rising unemployment and the subsequent exploitation of the migrant workers in the city.

‘With how my hands are right now, it’s very hard to pull a rickshaw’

Most rickshaw pullers in Kolkata do not have the choice of occupational mobility Amit Datta

Basant Das, who started pulling the rickshaw when he was 17 and is now, at the age of 57, struggling with trembling hands, offered to share his experience as a rickshaw puller. He said: “It’s a tough job. We don’t even earn a lot. My hands became weak after about 20 years of doing this work. With how my hands are right now, it’s very hard to pull a rickshaw. It takes a lot of strength.” When asked why he continued to work in this occupation, despite the difficulties, he said: “I don’t know what I’ll do if they stop me from being a rickshaw puller. How will I earn money? I tried working in a steel factory, but pulling the rickshaw is the only work I know. I don’t even have a very long life ahead, so why should I stop doing the work that I’ve been doing for so long? I can’t start something new. They [government] won’t even give me any money. I’ll have to earn it myself.”

While Das operates his vehicle out of Hatibagan in the northern part of the city, his experience represents the lives of hundreds of rickshaw pullers across Kolkata, wherein they felt stuck in time. Most of them do not have the choice of occupational mobility due to an increased demand for technical and mechanical skills, which they lack.

Mukhtar Ali, 57, spoke about the decline of the hand-pulled rickshaw. “Our rickshaws aren’t prominent anymore. Rickshaw is the only vehicle that can travel through the monsoons in the narrow lanes, but no one cares about that. Even our fares have increased significantly.” He looked across the bustling lanes of Ganesh Talkies, where he begins his day ferrying a handful of passengers and recalls the time when he had just started pulling the rickshaw in the neighbourhood. About 27 years ago, the maximum fare for a trip was Rs 2. “With that amount, we were able to sustain ourselves and fulfil our basic food requirements. It included two meals per day — fish, pulses and rice. But now, things have changed. Today, due to new factories, things have become so mechanical and expensive that we have to charge fares as high as Rs 100 for a trip, just so we can put some food on the table. No one wants to get on the vehicle as a result.”

‘People only come to us when they want pictures of our rickshaw’

While the emergence of factories and industries plunged the hand-pulled rickshaw into precariousness, it also made people associate the vehicle with an element of nostalgia. According to 65-year-old rickshaw puller Kishore Singh from Beadon Street, “people only come to us when they want pictures of our rickshaw. They seem very fascinated by it. Foreigners come to us, click pictures, give us a small amount of money and then leave”. This “fascination” with the rickshaw and its subsequent romanticisation has acted as a catalyst in pushing the vehicle to the margins.

Mukhtar Ali adds how “our rickshaws have been reduced to mere objects that provide evidence of English sahibs. Woh uski mahima karenge [they will glorify it] and then they treat our vehicle as if there is something bad about it; that it’s continuing the British Raj in some way.”

The rickshaw is, thus, simultaneously romanticised and ostracised.