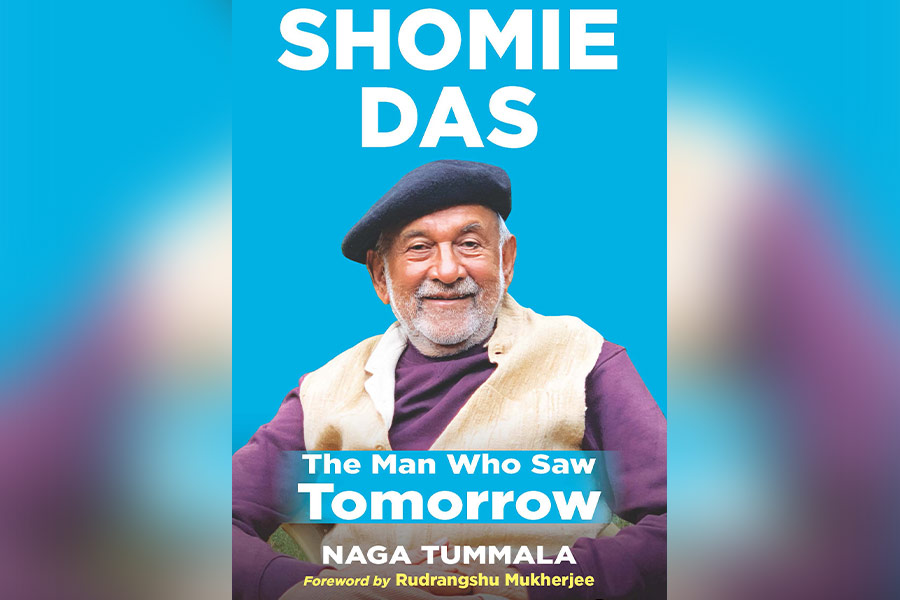

Shomie Das, the only person to have headed three of India’s premier legacy schools — Mayo College, Lawrence School, Sanawar, and The Doon School — passed away on September 9, 2024.

Das helped shape thousands of minds as he contributed to the setting up of 70-plus schools.

The visionary on a quest to make education a source of curiosity, creativity and character, passed away in Hyderabad 11 days after his 89th birthday and 10 days after the launch of a book chronicling and celebrating his work and vision.

Written by Das’s long-time associate and mentee, Naga Tummala, The Man Who Saw Tomorrow (Om Books International) is a deep dive into the mind and journey of a unique educationist and his incisive and insightful look at the education system today in India.

The following excerpt from the foreword to the book, written by Rudrangshu Mukherjee, chancellor of Ashoka University, serves as an apt snapshot of the man and the educator.

Committed to tomorrow

Shomie, after having studied physics at St. Xavier’s College, Kolkata, and Emmanuel College, Cambridge, chose to become a schoolteacher. Some of my admiration for him stemmed from this decision of his very early on in his career. I have heard from some of Shomie’s former pupils that he was an excellent classroom teacher. Shomie himself has told me that he missed teaching when he became headmaster of Mayo, Lawrence School, Sanawar, and Doon, and was forced to reduce his teaching load. The loss of a good teacher was more than compensated by Shomie’s role as an institution builder.

This book is about the building of an institution, Oakridge School, in present-day Telangana, and of Shomie’s lifelong commitment to school education. Most people mouth the cliche that today’s children are tomorrow’s future. Shomie walked that talk and devoted his life to educating children and to building institutions which would enable that education.

I must emphasise here that Shomie’s ideas about education transcend the conventional notion of what education is about. Shomie has never believed that education is only about doing well in examinations. His ideas go to the root of the word — the Latin educere, to draw out. He is passionate about opening the doors and windows of young minds, to stoke their curiosity and to expand their intellectual landscape. Education, for Shomie, has never been transactional.

…

This book is the story of the interface between two entrepreneurs, Naga Prasad Tummala and Rajasekhar Yarlagadda, and a dedicated educationist. It has many stories and many lessons. While I am not sure that Shomie is prescient, what I am certain about, having known Shomie for nearly five decades, is that he is someone who is committed to tomorrow. Very few, even the best amongst us, have that commitment. Age has not withered that intensity in Shomie.

Building character outside the classroom

The following excerpt from the book reiterates Das’s belief in the unique potential of every child, a belief that has been at the core of his life and work.

Another way of encouraging holistic development is to take children out of the classroom as much as possible. That’s vital, Shomie says, to building physical and physiological strengths and also primes children for a life of activity. This again brings us back to (Kurt) Hahn who thought risk-taking was a crucial element in character-building. Hahn was responsible for setting up a landmark initiative: Gordonstoun for Rescue Services. Since the school was by the sea and close to the mountains, too, there was a coast guard service and a mountain rescue service as well. There was also a fire service team.

“Hahn thought that you must teach children to rescue lives,” Shomie would often say. “He felt that was equivalent to fighting for your country in times of war. He always believed that one has to learn to be alert, to see if someone is in difficulty and to go and help them… Hahn trained children to be good citizens.”

Shomie tried his best to implement some of these thoughts at Doon since he, too, believed these were important for character-building. He even set up an ambulance service. In those days, ambulances were hard to find. When an earthquake struck Uttarkashi in 1991, they drove the ambulance and carried out rescue work in villages, pulled people out from under piles of debris and took them to hospitals.

But the service was eventually discontinued. “Today, these things are considered a waste of time. Principals are under pressure to get the best academic results. Character-building takes a back seat,” Shomie rues.

There is no point in being an educator without believing in the potential of our children

He would often talk about another incident, which happened while he was at Gordonstoun. Shomie had taken 14 boys to climb a peak called Ben Alder. They had camped at the bottom of the peak for the night and set out the next morning. As they climbed, a severe blizzard started. The wind was strong and the blizzard froze their eyelids, which meant they were climbing without being able to see where they were going. On their right was a sheer slope.

“All we had,” Shomie recalled, “was a map and a compass. Then this boy said, ‘Sir, let’s put the map on the ground and align it.’ In the strong blizzard, we managed to do that. We aligned the compass and walked 10 paces. Then we did it again, another 10 paces. Finally, this boy led all of us to safety. The interesting thing was that, in class, he was a very dull sort of fellow. But his real character came out in this tough situation.” Shomie calls this a universal phenomenon.

Later, while he was at Mayo, he would lead another rescue effort during a flood. Shomie had received a call from the district collector who asked if they had boats. “We did. So, off I went with 10 boys and one master in our boats. We did a lot of rescue work, helping people perched on trees, taking them home, feeding them and giving them shelter. Among the boys was a fellow called Anil, who sadly is no more. He was very naughty but I had deliberately chosen him. The master had strongly advised me not to take him but he turned out to be the best in the whole group. He volunteered for everything difficult. There was hardly any drinking water. So, Anil would walk a couple of kilometres, often at night, through flooded areas to fetch drinking water. His character came through in that crisis.”

Shomie is an incurable optimist. And if there’s something I have learnt from him, it is this. There is no point in being an educator without believing in the potential of our children, our future.

(Buy the book here.)