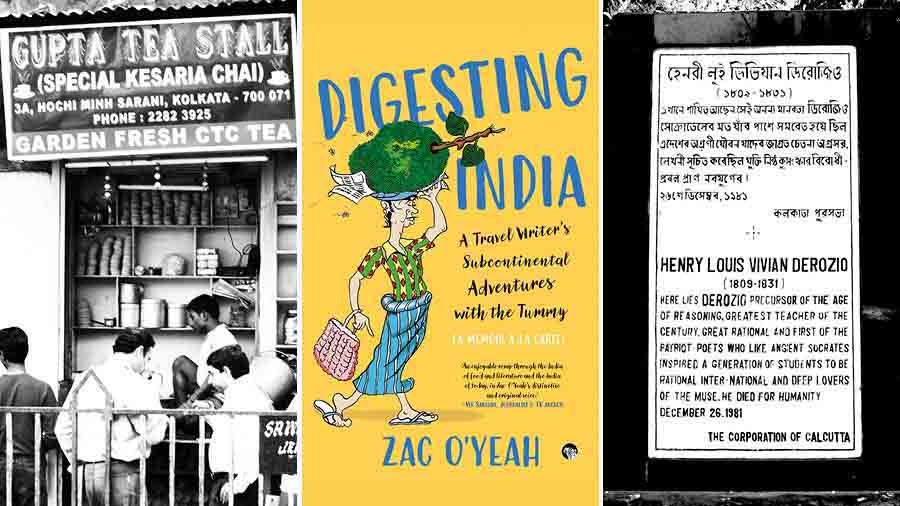

Scandinavian-born author and funnyman Zac O’Yeah has been exploring the sub-continent for over three decades. The writer of the detective stories, the Majestic series has lived, loved and written in India for over three decades. In his latest book, Digesting India, published by Speaking Tiger, he brings together his myriad culinary adventures as he travelled and ate through the country — from discovering Goa’s literature scene over glasses of cashew feni to finding out what astronauts sip on in space.

When his travels brought him to Kolkata, Zac found the delights of pice hotels, the nostalgia of Park Street, the culinary history of Jorasanko, and more. In the following excerpt from Digesting India, we get a peek into the adventures of his taste buds and grey matter in Kolkata…

************

As a food tourist in his [Rabindranath Tagore] house, I am frankly speaking most touched by the kitchen where one can see a rather — from a modern point of view — primitive stove, upon which I imagine that the womenfolk prepared his sugary jasmine tea and his meals. He usually wanted Bengali food for lunch (mutton curry without chillies but tinged with sugar), followed by Western for dinner with soupy starters, meaty or fishy mains, and pudding for dessert. But he was against fusing the two — and all was eaten with imported cutlery, according to a story I heard from another museum visitor who seemed to know a lot about Bengali food culture. Coincidentally, Tagore’s niece Prajñasundari Devi wrote one of the earliest Bengali cookbooks in 1902 and not many know that the bard wrote a slogan to market tea — apart from inventing several desserts such as modified jalebis to tantalise the Bengalis’ collective sweet tooth.

Prajñasundari Devi Wikimedia Commons

This obviously makes me hungry for Bengali specialities so I head off, rather impatiently and not too far, to Siddeshwari Ashram in Mirza Ghalib Street (near Janbazaar) to have lunch at the no-frills and very business-like ‘pice hotel’— one of the last such remaining, and known by that name because once upon a time food items could be bought for one paisa. The idea was that instead of ordering a full meal, money-minded customers could pick as many items as they could afford. Today, of course there aren’t any paisa coins in circulation and dishes are pricier at Rs 100-200, but well worth it as their chingri is the biggest, freshest, juiciest estuary prawn I’ve ever sank my teeth into, virtually lobster-sized, and fried in a creamy gravy tempered with the typical five-spice blend ‘paanch phoron’.

Earlier, the town was full of similar canteens to feed labourers who migrated here in search of work. Even this one existed in Tagore’s days so he, being a foodie, may have ordered home-delivery or, perhaps, even sat at one of the marble-topped tables to sample its fare along with his culinary clubbers.

Suruchi at Elliot Road Arijit Sen

Another, about half-as-historic place but one that I love, is the all-women-run Suruchi (89 Elliot Road) where the divine bhetki tastes truly motherly. The perch-like fish is robed in a banana leaf that traps the aroma of the yellowish mustard paste and other spices during the cooking process. The one pungent note peculiar to Bengal’s fishy dishes is ‘shorshey tel’, I think that may be how it is to be spelled, the local mustard oil that is a must and adds an unusual sharpness like a winding guitar solo in a 1970s’ heavy metal tune. Apparently, it is because they view fish to be a vegetable of sorts, albeit one that swims and thinks, that the Bengalis have such evolved intellects and always were pioneers of modern literature. It is said that only every seventeenth Bengali is a vegetarian, the other sixteen love fish — including heads, brains and all.

One more experience of literary interest is the Park Street cemetery. There’s something about its decay that makes it utterly realistic. No plasticky Disney makeup covers its scars, everything is the real deal. The caretakers nap inside the cool crypts of towering tombs that constantly remind of exotic ways to die—the descriptions range from monsoon melancholia to choking on pineapples. It’s hard to find anything comparable outside New Orleans’s voodoo walks that take one to horror-movie spooky cemeteries, or Paris where everybody who is anybody, from Jim Morrison to Chopin, take final rest at Père-Lachaise, or London’s supposedly occult graveyard at Highgate which has an interestingly swinging party crowd (provided that there’s an afterlife) including Karl Marx whose tomb has been bombed several times, one alleged vampire who is said not to rest peacefully, not to forget The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy author Douglas Adams, plus music industry phenomena such as Malcolm McLaren (of Sex Pistols fame) and George Michael (of Wham!).

There’s something about the Park Street cemetery’s decay that makes it utterly realistic Wikimedia Commons

The Park Street cemetery’s fame with film buffs has grown after the 2010 Bengali movie Gorosthaney Sabdhan based on Ray’s story (translated into English as ‘The Secret of the Cemetery’) turned out to be a box-office success. And the literati are keen on exploring the necropolis of which Rudyard Kipling wrote in one of the more hallucinatory chapters of City of Dreadful Night: ‘The eye is ready to swear that it is as old as Herculaneum and Pompeii. The tombs are small houses. It is as though we walked down the streets of a town, so tall are they and so closely do they stand — a town shrivelled by fire, and scarred by frost and siege. Men must have been afraid of their friends rising up before the due time that they weighted them with such cruel mounds of masonry.’

As for myself, I bite into a clove of garlic as I enter the cemetery, well aware of the rumours of haunting, how visitors experience spells of breathlessness and dizziness due to weird shapes peeking over their shoulders in their selfies. One tomb is claimed to occasionally bleed, sadly not when I’m visiting.