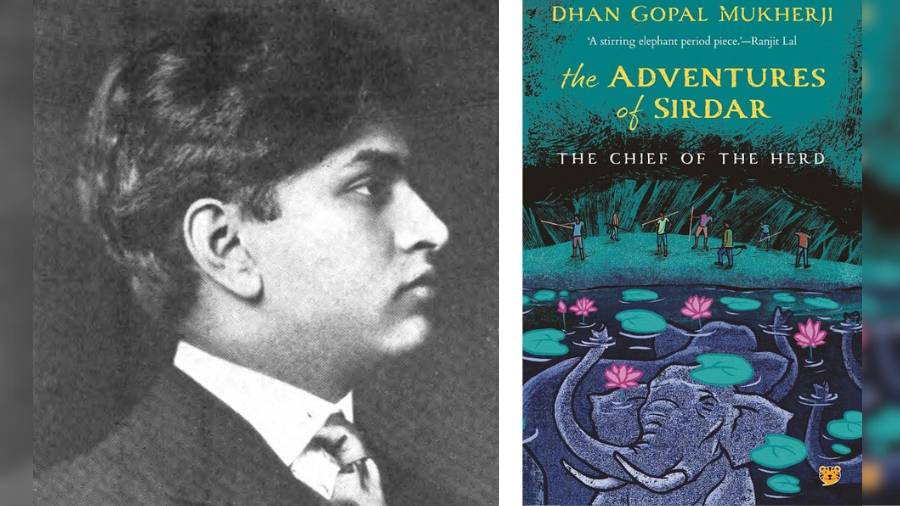

A pioneer who initiated Indian writing in English in the global literary landscape, Dhan Gopal Mukherji was born in Tamluk, Bengal, in 1890. His assiduous observation of the intricacies of life in the woods near his village taught him to soak in the ways of the natural world and understand the language of the wild. His intimate relationship with the jungles of the East and the myriad animals they house shaped most of his children’s books that brought him critical acclaim.

Talking Cub (an imprint of Speaking Tiger) published a retitled edition of The Chief of the Herd as The Adventures of Sirdar: The Chief of the Herd in 2023 to transport the readers into the magical world of peace that Mukherji portrayed the forests as.

My Kolkata discussed the continued relevance of this pioneering writer with Sudeshna Shome Ghosh, the publisher of Talking Cub.

My Kolkata: Mukherji was the first and the only Indian writer to win the Newbery Medal. Yet, not many remember him for his art. Where would you place him in the landscape of children's literature in India?

Talking Cub: I would accord Dhan Gopal Mukherji the place of one of the first Indians to write in English for children, and do it successfully. Not just for being recognised in the West (he was also living there at the time), but also for writing about his own country, its flora, fauna, and ways of life with empathy with understanding, and as a voice devoid of the racism that was inherent in the works of better-known writers like Rudyard Kipling. It is a pity he is largely forgotten today and not known to laypersons for his immense contribution to the oeuvre of children’s writing by Indians. I have heard writers like Ruskin Bond mention him, and one can see the similarities in some of their preoccupations, particularly in the way they connect with nature in their writings and how they are able to show nature in all her complexities and glory for children.

After graduating from Stanford University in 1914, Mukherji’s move to New York City in the next decade proved fortunate, for E.P. Dutton began publishing his books. Gay-Neck: The Story of a Pigeon, which draws on his childhood experiences with a flock of forty pigeons, was published in 1927. It won the John Newbery Medal for excellence in American children’s literature in 1928, making Mukherji the first and the only Indian to have won this award so far.

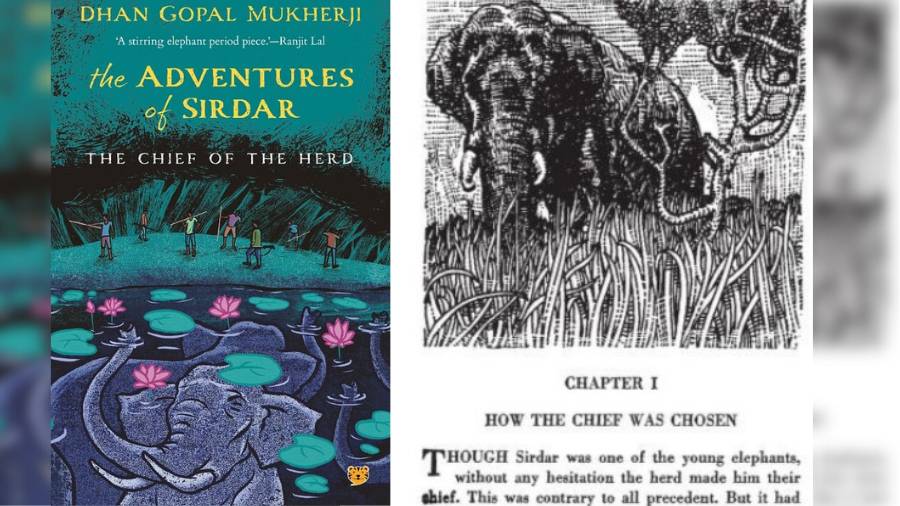

The opening pages from the originally published, illustrated title of the book

What motivated you to retitle and publish one of Dhan Gopal Mukherji's works?

I was reading some of his books that are now out of print and was particularly struck by this one for its exciting story, the information it gives about elephant life, and the beauty of its writing while describing forests and forest creatures. Here was a story where animals were dignified and majestic, and humans appeared only as a part of the story. I was also impressed by the thread of conservation that lies unsaid in this novel. If we want our children to be responsible citizens of this planet, we need to present to them books where they can experience the beauty of animals and forests and understand their own place in the scheme of things. I felt The Adventures of Sirdar does this beautifully.

With digital content flooding children’s and young adults’ minds, do you believe children's literature is getting the attention it merits?

Yes, it is true that books are vying for space alongside digital content. And yes, it is difficult to make books as exciting as video games and movies if one sees them superficially. I do believe many parents and schools recognise the importance of reading and work sincerely towards building a reading habit among the young. However, we have a long, long way to go in this area. And it is not just digital content that is to be blamed, we have also failed to give adequate attention to the existing books and authors among us. Indian children’s writing lacks support from bookstores which are flooded with imported books or books by only a few Indian writers. The media too relegates children’s books into a corner or sees it as a niche subject.

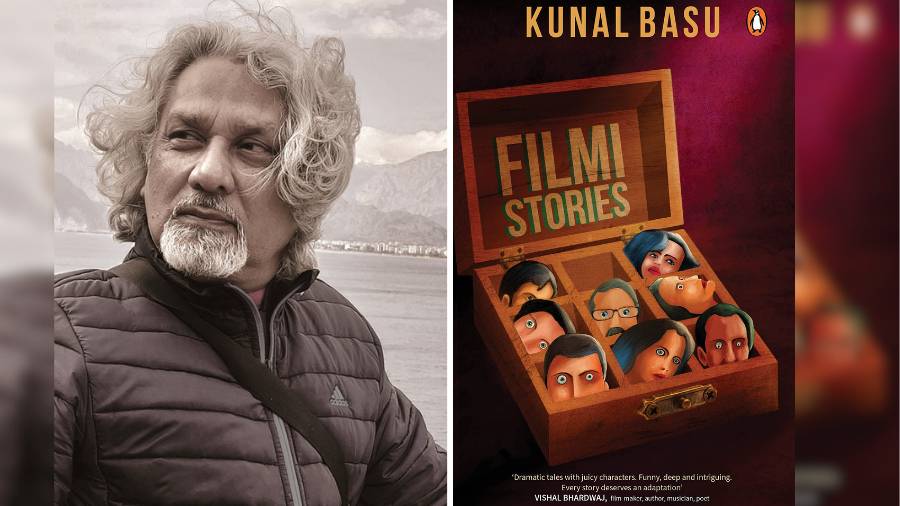

Started in 2017, as an offshoot of Speaking Tiger Books, Talking Cub has published over 150 titles

Share with us the journey of Talking Cub and your vision for it in this fast-evolving world.

We started Talking Cub in 2017, and our aim has consistently been to publish good quality original writing from India, in any genre. We started with mostly fiction, and now we have a list of almost 150 titles that range from board books to books for young adults. Our books and authors have won major Indian awards for children’s writings, and we have seen some amount of commercial success as well while being critically appreciated. As children’s publishers, it is important that we keep abreast of the times and that our books reflect the issues of today while being diverse and sensitive—and fun! Good writing is timeless, and for us, that is always the key to why we publish a book—that something in it is unique, and will be memorable for the child reading it.

An Excerpt from 'The Adventures of Sirdar: The Chief of the Herd'

With striking simplicity, the author shows humans as the Other in The Adventures of Sirdar — an inimical force encroaching into a space that is not theirs. Sirdar, the magnificent tusker who began leading the herd at a young age, teaches readers the virtue of remaining composed through crises because “unafraid you are safe, afraid you are dead” — the unwritten rule of the forests that holds true in the human world as well.

Here’s an excerpt from the collection, the story — How the Chief was Chosen

***

The new book cover, and (right) the illustrated opening page of the chapter 'How the Chief was Chosen'

Though Sirdar was one of the young elephants, without any hesitation the herd made him their chief. This was contrary to all precedent. But it had to be done because the crisis at hand was too great.

After all, to Sirdar they not only owed their escape from capture, but also from death. Out of sheer gratitude and respect for his ability they chose him their leader. In the history of the herd no one only thirty years old had been given that honour before. In fact none of the aged elephants could recall electing a chief who had not seen at least fifty summers. They said, however, ‘Sirdar is young in years but old in intelligence.’ That unusual things happen even among elephants is an old adage. And the series of events that led up to Sirdar’s election were most unusual.

One day early in the morning the herd had scented the presence of their eternal enemy—man. The more they moved away from that scent, the nearer it drew. No matter which way they turned they were faced with the presence of man. They felt caught in a ring of humanity. Every member of the herd—calf, cow, and bull—switched their trunk east, west and north in order to locate in one direction an inch of air that was not charged with the odour of men. Alas! there was none! What were they to do now? Whither must they run for safety and cover? Their ancient chief, ninety-five years old, decided to go north. A fatal decision, no doubt; but they had to obey as soldiers obey a general. Everyone knew that they were exposing themselves too much, for only a mile to the north of them was open country. How they could hide in such a place from the pursuit of man passed their understanding. But since the way to handle a command of the chief was to obey it, they proceeded to the only direction whence, he said, came no scent of humanity. Thither must they repair first and take counsel afterwards.

Had that aged fellow put up his trunk five feet above his head, he would have learnt that in the north, too, was man and worse—a gigantic trap. Since the hunters wanted them to go northwards into the Kheddah trap, that one direction was kept free of human scent. For all the men were hiding on trees whence their odour was blown up by the wind far beyond the knowledge of the hathis. As they went north, the herd drew close to the Kheddah. All the expert elephant trappers of India had come this year armed with high-power rifles, with the intent to kill all the bulls. They were hiding on tree-tops in order to be able to aim carefully at the most vulnerable parts of the elephant’s head. The entire herd knew nothing of that. The hunters’ purpose was twofold; they meant to capture most of the herd and to kill those bulls who might flee the Kheddah. Since the males of this particular herd had the best tusks in India, the hunters felt all the more eager to shoot.

They surmised from their perch that the ivory they might get would be vast, for they noticed that more than one bull had tusks over five feet long, while the Chief’s two dantas, teeth, appeared to be about seven, the longest tusks available at the time. Since this was the last year of elephant shooting in Indian history, the hunters and trappers had come prepared with the most merciless weapons. Each man felt that since the law prohibiting elephant killing was coming into force in another week’s time, he must shoot as many as possible in case the herd stampeded. Business firms that dealt in Indian ivory in Paris, New York and London, had paid and armed those huntsmen to perfection. They were going to kill the most magnificent pachyderm, not that they enjoyed slaughter, but because they were hungry folks who must earn their daily bread.

After the herd had marched closer to the open country, they were called to attention by the shrill trumpeting of Sirdar who was bringing up the rear. He gave a sharp short call. The Chief snorted at the herd which meant: ‘That young fool at the rear needs punishing. Follow me. March.’

Ere they had put forward another foot, the flock heard distinctly: ‘Kunk—Know—Kon—man ahead, man above, about turn, retreat.’

That undisciplined cry of Sirdar enraged the Chief so that he bellowed furiously: ‘Follow me—Tonk—Too.’ Just then something happened that froze his muscles. In order to trumpet well, the Chief had thrown up his trunk so high that it had not only obtained the odour of man overhead, but it had literally grazed the latter’s leg, knocking him down. What a shock! He went round and round quickly trampling on the wretched human. Simultaneously he trumpeted to say: ‘Flee—man, man—flee. Khron—hun—Gromm.’ In an instant a man from another tree shot him through the ear. The bullet proved fatal. Like a mammoth stricken, the master of the herd fell. But instead of dying like a dumb beast he used his ebbing strength for those who followed him. With his last breath he trumpeted to them: ‘Ghoom—ghoon,’ meaning ‘Follow Sirdar.’ Thus died the noble Chief. He died not a brute, but a master.

In the meantime Sirdar, who had seen a man on a nearby tree and had shouted his warning just in time, was doing all he could to lead the herd to safety in the depth of the jungle. They were all running southwards after him. Shots rang out from boughs behind and over them. Trees crashed to the ground before them as they thrust their hard heads forward. Their feet crushed all opposition under them till the thunder of their flight stilled all other sounds.

Sirdar was cool and unafraid. That is why he could extricate nearly the entire herd from the Kheddah, trap. He went on and on. With every step the stench of human presence became more and more formidable yet he pushed south, roaring, trumpeting and squealing. ‘On, on, on, into the thick of that humanity. Kill the murderers, kill,’ he said to himself and to his friends.

The effect of his bellowing was magical. They rushed through an army of beaters who like squirrels ran up all kinds of trees.

‘So that is man,’ Sirdar said to himself. ‘They run faster on their two feet than we on four. How easily men take fright.’

In thirty more minutes they vanished in the depth of the jungle where man had never penetrated. As soon as they had recovered their presence of mind automatically they went to a lake not far off and washed themselves. After washing away all taint of hate and fear they came ashore.

Since a herd must not remain leaderless, they all assembled under the tall trees, and in a few minutes’ time chose one. It was Sirdar—that young male who had saved and led them through dire danger. Had not the old Chief said ‘Follow Sirdar’? That was enough to settle his election. ‘Because we owe our lives and freedom to him, the least that we can do is to make him our Chief. Kunk, Kunk, Kunk,’ they roared. Thus acclaiming him, they took their oath of allegiance to their new leader who was more humbled than pleased by such a turn of events.