We just finished Durga Puja and Navratri. And Diwali is upon us. Most athletes are at home, spending time with their families or celebrating with coaches and teammates at some far-flung training facility. Let’s leave complicated things aside for the day and start with a couple of funny stories of athletes trying to be normal.

The dinner plans of a boxer and a sprinter

We are at the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Vijender Singh, a Haryana-born boxer who models part-time for some extra cash, is punching his way into history. But before his semi-final bout, he is calm. Unusually so, in fact. People around him are shocked at how relaxed he is before stepping into the ring for an Olympic medal.

Even his coach becomes uncomfortable at seeing him so zen and asks him: “What’s going on? Aren’t you nervous?” The tale goes that Vijender grins and responds: “Coach, I’m thinking about what I’m going to eat after the fight. I’ve been eating the same bland food for days! Win or lose, I need some butter chicken and naan!” The coach frowns but Vijender’s teammates crack up. After all, who would have expected butter chicken to play a starring role in the build up to the biggest moment in Indian boxing history.

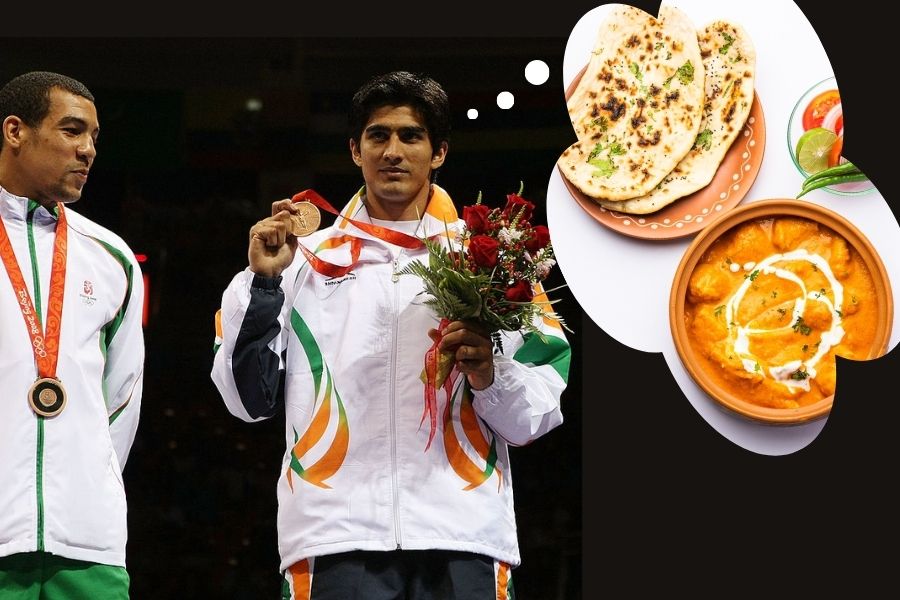

Vijender Singh took on Cuban boxer Emilio Correa with — reportedly — butter chicken on his mind Getty Images, Shutterstock

Vijender fought with concentration and his usual steely aggression, but ended up losing the semi-final to Cuba's Emilio Correa. He still got the bronze, becoming the first Indian boxer to win an Olympic medal.

In the same Olympic village there was another athlete on the verge of rewriting history. But he was getting sick after eating unfamiliar local food. Usain Bolt’s solution was simple: go to McDonald’s and eat 100 chicken nuggets every day, because he could not possibly have gotten sick after eating that. Bolt’s love for nuggets turned into a bit of obsession, and after his record-breaking victories, he credited the nuggets for his success.

The hero and the villain

Athletes are no different from you and me in most respects. But we struggle to treat them normally. We often raise them on a pedestal. In fact, in our country, we have a long cultural legacy of hero worship. We find the heroes we crave in movies, and increasingly, in sports. That is not a bad thing, as long as we are aware of the pitfalls.

What we are definitely less aware of is that we also treat athletes as inferior, people to whom we need not extend the most common courtesy. The recent Diljit Dosanjh concert at the Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium in Delhi is a case in point. The stadium was rented out for the concert — that’s normal; subletting and multi-purpose use make sport venues sustainable across the world. The problem is that the organisers and the concert attendees left the place trashed. Sporting equipment were shoved aside, beer bottles were thrown into long jump pits, and rotten food was left on the athletics track. Athletes were unable to access the venue for 10 days before the concert and in all likelihood will have to wait another 10 days to be able to resume training there. Think of it this way, you rented out your home as an AirBnB and someone left it in ruins. How would you feel?

Reportedly, a crowd of 40,000 attended the Dil-Luminati Tour concert in Delhi X/@diljitdosanjh

In this case and in many cases, the attitude seems to have been, the Olympics have just ended, and you are training for the national and Asian championships, so how does it matter? We forget that the four years that lead up to the Olympics are the years that get us the medals, but we are quick to point fingers — from the armchair, of course — when the medal tally does not meet our expectations.

We are similarly unkind when athletes fall from the pedestal we have put them on. Very, very few can occupy a pedestal for good. For most, it is only a matter of time before the inevitable decline starts. But we often do not let this fact of life come in the way while assigning blame.

Ideas and individuals

I was in Rome recently. I have had the privilege to travel around historical sites in India as well. Do you know which monuments have survived from these ancient civilisations? Not the ones dedicated to individuals, but the ones dedicated to ideas.

The colosseum in Rome was named after the egotistical Emperor Nero (who was a bit of a madman, too) installed there a 98ft-tall statue of himself modelled on the Colossus of Rhodes. No trace of the statue exists any more. But the idea of the Colosseum as an arena where excellence in sports was celebrated — gladiator fights were the Roman sport — persists. I have been to more than 50 stadiums across the world and most of them share striking similarities with their ancestor, the Colosseum.

While Nero’s 98-foot-tall statue of himself isn’t there anymore, the Colosseum still stands and became as a blueprint for modern sports arenas

So, here’s a suggestion. Let us start treating athletes as normal people who can do incredible things in their domain. Just the way we might treat a financial analyst or an air traffic controller. That way we can hold them accountable for successes and failures. More importantly, we can hold ourselves accountable, too.

Dr Sahen Gupta is a Kolkata-born, India- and UK-based psychologist who divides his time between mental health support and high-performance coaching. As the founder of Discovery Sport & Performance Lab, he works not only with Olympians and other top-level sportspersons, but also with CEOs and other professionals striving for excellence. Dr Gupta’s mission is to simplify complexities of the mind into actionable and simple ‘doables’ that allow individuals to be mentally fit.