The world seems to be passing through a turbulent phase. At least a more-turbulent-than-usual phase! The Copa America that Argentina won saw violence and near riots in the stadium. Former US President and current presidential nominee Donald Trump got shot at. A neighbouring country is seeing widespread student protests that have resulted in scores of deaths. And we have not yet referred to the two ongoing wars.

In this chaos, it is normal for people to look for continuity. That, too, seems elusive. In tennis, it is not the ever-consistent Novak Djokovic who won the French Open and Wimbledon despite coming close. And in the upcoming Olympics, the star or the favourite has gone missing from all but a handful of sports. Getting some work done might have seemed the best possible option if you got depressed about your bank account while doom scrolling through the Ambani wedding. But wait… even Microsoft went down putting paid to your work plan.

What is psychological safety

We are usually very aware when we do not feel safe. The alarm bells in our head immediately go off. We get tunnel vision and try to find a way out. This is what happens when, say, you are outnumbered 100 to 1 by hostile people in an unfamiliar place or a group of toughs eye you in a dark alley. In addition to these obvious examples, you might not feel safe even when everything is ‘normal’. For example, feeling uneasy in a meeting with your boss or being worried about what your friend will say about your new partner.

Sometimes you might not feel safe even when everything is ‘normal’, and that is the realm of psychological safety Shutterstock

This is the realm of psychological safety. Let me tell you a real-life story. I supervise a graduate student who applied for and was accepted into a scholarship funded PhD programme at a university in the UK. I had been quite a tough taskmaster during the preparatory phase of the admission interview, but she remained unfazed. I challenged her as much as I could, explained my reasoning and was supportive when she needed support. The interview board was delighted with her and offered her the programme. But later told her that being an international student, she would have to pay a higher tuition fee that would not be covered by the scholarship she had got. The student did not feel ‘safe’ enough after that to take up the offer. She did not want to be constantly wary of unpleasant surprises.

At the individual level, psychological safety allows us to feel comfortable about speaking openly, expressing our concerns and taking risks. When we feel our suggestions, questions and opinions are respected and valued, we feel psychologically safe. The absence of psychological safety typically reduces performance. We see this all the time in sports teams and in corporate offices. In both settings, people restrict themselves because they are afraid of making mistakes. Fear stops them from pushing the limits and therefore, they do not achieve optimal performance levels.

Types of psychological safety

The risk of getting hit by a truck is a very different type of ‘unsafe’ compared with the risk of getting pooped on by a pigeon. Psychological safety, too, has different levels and layers. The first type is called ‘inclusion safety’, which is the level at which individuals feel accepted and included in a team or organisation. If a player is not included in discussions, they feel left out and there is no belonging. That player will not give their all for the team. This is a key element in team sports.

One of the types of psychological safety is when individuals feel accepted and included in a team or organisation Shutterstock

The other kind of psychological safety is ‘learner safety’, which allows an individual to feel safe about asking questions and getting feedback without the fear of embarrassment and discrimination. This is especially important for youngsters, because if their curiosity is killed, they struggle to learn. Learner safety is at play when children quit sports because of difficult or overly critical coaches. This, of course, is not to say that coaches should not point out mistakes. Ideally, they should be able to do so without making the learner feel psychologically unsafe.

When we look at high-performance sports, there is also an element of ‘contributor safety’, which is the assurance that you can contribute to the overall direction of the team. This does not mean that there is no hierarchy. It means that within the hierarchy, you are able to provide to the level above feedback and inputs that are heard and considered. This is a key part of a team sport when we have a dynamic of junior and senior players.

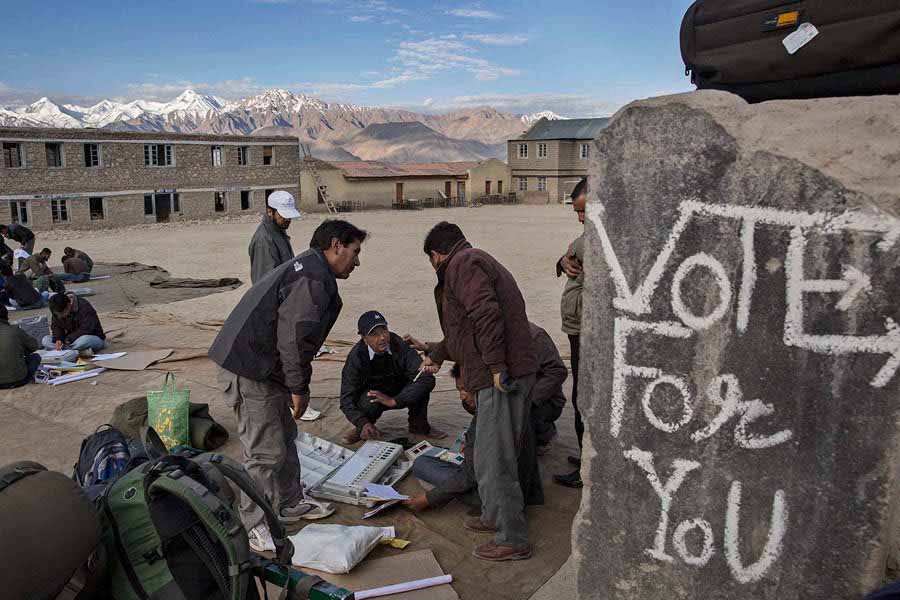

Can you think of another example? Maybe closer home? Maybe at your home? When kids contribute to vacation plans or suggest a restaurant for dinner and every now and then, their suggestions are taken. Another example is elections, where the voter feels psychologically safe because their vote is being recognised and acknowledged as a contribution.

The final type is ‘challenger safety’, which allows for arguments and disagreements while voicing ideas with reasoning. This is an important part of a coach-athlete relationship in professional sports. It is important for coaches and athletes to be able to have regular disagreements in the pursuit of optimal performance. Same for teammates in professional sports. All arguments are not bad. In fact, healthy disagreements often lead to better team performance and improvement.

How do we know if we are psychologically safe?

It is a cruel irony that the easiest way to know if you are psychologically safe is to feel rather unsafe Shutterstock

It is indeed a cruel irony that the easiest way to know if you are psychologically safe is to feel rather unsafe. This is what makes establishing our mental safety so very difficult. Unlike an oncoming acidity episode, this one builds up without our awareness by slowly eroding or limiting the way we express ourselves. The first warning sign is when you feel like you cannot speak up. The second is when you feel it is difficult (or even hopeless to ask for feedback). The final one is when you feel restless and jittery about everything you do. Maybe that is when it is the end of the road for you for whatever you had been doing, and time for a change of scenery.

Dr Sahen Gupta is a Kolkata-born, India- and UK-based psychologist who divides his time between mental health support and high-performance coaching. As the founder of Discovery Sport & Performance Lab, he works not only with Olympians and other top-level sportspersons, but also with CEOs and other professionals striving for excellence. Dr Gupta’s mission is to simplify complexities of the mind into actionable and simple ‘doables’ that allow individuals to be mentally fit.