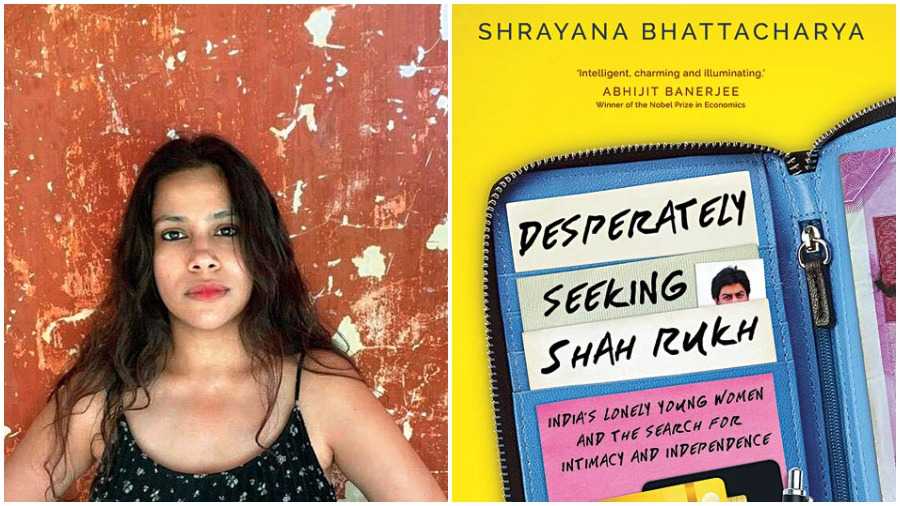

To say Shah Rukh Khan has been the ultimate dream would be a gross understatement in a country that has always surrendered itself to the star, more than the actor. Has there been a more recognisable phenomenon in post-liberalisation India that has waved across social classes in such an unfazed and penetrative way? Unlike personalised odes addressed to King Khan who has ever so nestled comfortably in the heart of every woman, so close, yet so far… so personal, yet so political, Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh: India’s Lonely Young Women and The Search for Intimacy and Independence (HarperCollins India) politicises the female gaze. For economist Shrayana Bhattacharya, authoring the book has not come out of blind obsession, but from a place of understanding and joyful admiration for the man, where the book is not really about Shah Rukh but about the countless women, amidst whose aspirations, anxieties and insecurities she attempts to locate the star.

The book navigates the lives of a number of women across social classes where Shah Rukh occurs as an embodiment of freedom, beauty and transcendence and a figment of their forcibly hushed desires. She brings into play the perspective of the Savarna woman and the Dalit woman on the same ground and shows how desire, accessibility and freedom have been mediated and crippled by patriarchal impositions.

In conversation with The Telegraph, Shrayana Bhattacharya talks about how this book arrives as a study, more than a homage, tracing the trajectories of women across class, caste and religion, intersecting at a common point where the personalised icon, Shah Rukh, stands.

How did the book happen?

The book happened as an accident, honestly. In 2006, I was sent to do a survey at a place called Bapunagar in Ahmedabad on incense stick workers and garment workers, who were actively unionising themselves and fighting their own battles. In recesses, I used to talk to them about popular Hindi cinema and asked them about their favourite actor, and it is then Shah Rukh was mentioned. When I listened very closely to these women talking about Shah Rukh, I realised they were not talking about him, but themselves — how difficult it was to earn money independently, have access to public places like the theatre and watch his films without a sense of guilt.

Shah Rukh was the springboard to these conversations, where they spoke to me about gender relations in domestic spaces. These conversations were a powerful illustration of how compromised the economic freedoms of women in our country are. Around 2013, I decided to work on this — through the language of pleasure, fun and fandom, by including accounts of women from both precarious and privileged backgrounds.

Was it the economist or the fan in you which spoke more to you in the process?

I think it was a sweet spot of both. In social sciences, we often do a disservice by only trying to approach people through the prism of our rigid frameworks. So, when I was talking to these people, the framework collapsed as we started fangirling over him. Fandom, to me, is more of an economic pursuit than a social one. Approaching it that way, there was a seamless fusion of both in the book. I’m very biased when it comes to

Mr Khan, but I’m also very biased when it comes to women in India. I’m very angry as a woman, where we have received the short end of the stick when it comes to economic freedom or justice. Trying to acknowledge my bias, I checked it against people from the industry and other scholars. Instead of me trying to Brahminsplain the economy to these people, I wanted to see how women from the bottom up perceived and talked about their economic realities. So, it was rather the social scientist in me that spoke and helped me gain transparency about how I wanted to present this.

Do you think there’s a sociological baggage associated with fandom?

There’s certainly a sort of gendered baggage which comes with it. If I would have written a book on seeking Sachin and cricket, it would have been immediately taken seriously in a country like ours, where cricket is a serious masculine pursuit. There’s this immediate discomfort whenever there is a conversation on female sexuality and sexual autonomy or even just women gushing over their favourite actor. The male and even aged female in-laws often find it very uncomfortable to have a girl talk about her favourite actor. To have his shirtless photo and the compulsion to hide it speaks about how extremely deviant it is considered to be. Thus, fandom, as I talk about in the book, is more of a line of social inquiry — a bridge creating language between two people who might not have a lot in common.

Does the icon of SRK somehow represent an illusion of choice to these women?

Yes, I think, it is very class specific. For women hailing from elite privileged backgrounds, he represents social mobility and scaling the way up to the top. For the emerging middle class, he is somewhat like a self-help guru. They rely on his words and his dispositions to initiate similar trajectories, that might materialise someday. But for women from extremely constrained spaces, he does embody a romantic and personal choice — the prospect of meeting a man who might just be ‘different’. And this distant hope of finding the man in cities. So, he does embody the narrative of the big cities. As Dil to Pagal Hai ends on the note of “Someone… somewhere… is waiting for you”, for women from such spaces, as talked about in the book, he represents the dream of ‘the man’ in the city. They are often unloved and unsupported in these romantic decisions. And love is not something you can offer a policy solution to. He is that respite.

The book highlights your personal experiences as well. How did you strike a balance?

Originally, I had thought I would approach it in a more academic way, but it was in 2013 I decided to personalise it. It is always in situating yourself in the text that you make it accessible beyond just academic quarters. In a city like Delhi, every relation is somehow guided by these specific codes which come across as performance art. This was my decision to not creatively perform anymore. I wanted this to talk to people who are exhausted with this performance, especially women, for whom it is often incredibly hard to exit the performance of socially scripted femininity. I am grateful to my editor for helping me strike that balance.

Do you think in this age of content-driven films, there is a death of the icon?

I think icons are becoming more localised. The Khans, to me, represent the last umbrella superstars. Over recent years, the space has evolved to be more democratic where we have seen on TikTok or YouTube local stars performing song or dance routines, which I think is fascinating. When it comes to The Khans, they embody history and nostalgia of over 30 years, which is extremely significant. While there is this democratisation, I believe the power will endure parallelly with the rise of localised icons. For people who are not aware of texts and theory, they rely on these very popular scripts of culture for that semblance of hope and comfort. And I think that is where they continue to endure.

What are your favourite Shah Rukh films?

Now, this is a very tough job. But to mention three, Zero, Kabhi Haa Kabhi Naa and Swades. And I think he has always been so presidential in all of his interviews as well.

What are you working on currently?

I want to write a book on Delhi’s parlour games — the performance art that we talked about. I also have something of a longitudinal non-fiction in mind, which will take me some time, just like this one.