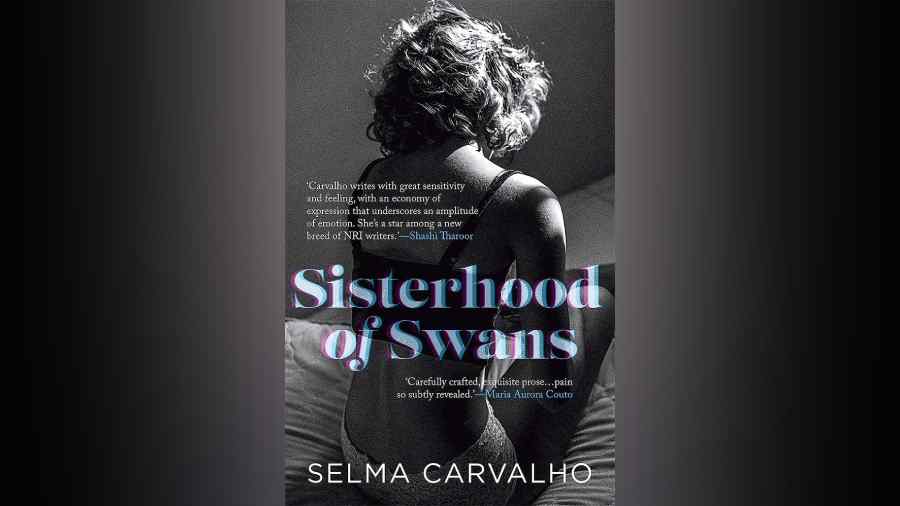

Selma Carvalho’s debut novella Sisterhood of Swans (Speaking Tiger; Rs 499) reads like a lilting poem. The heart soars as she takes one on a tumultuous roller coaster of sensory feelings only to have it drop back to reality with gritty conversations between Anna-Marie Souza and the people who surround her.

Anna craves the attention of her father who left when she was 10. While she jabs at her mother for not being able to hold on to her man, she melts under the touch of her suitor Sanjay in the dark alleys of suburban London, as he abandons his wife at home for these rendezvous. Anna feels the diabolic pressure of an imagined intimacy with Sanjay that is allegedly borne from a shared sense of cultural roots. She sees the neatly labelled bottles of spices in the airless kitchen in his small apartment and thinks of the unknown presence that still haunts the house. And she also feels a disconnection with her surroundings because of her roots. She watches a match at a pub, with everybody around celebrating a win, and feels alienated wondering –– “Before us lies the wide chasm of an England we can’t cross and the inescapability of an ethnic alienation we can’t deny.”

This is a the story of Anna-Marie Souza, a second generation Indian immigrant of Goan heritage, navigating the cruelties of life while searching for a partner.

Her need for a man is looked down upon by her Indian men-hating mother who enquires if this need is some kind of ‘reverse feminism’. But it is her broken home and chaotic childhood that aides her loss of sexual agency, driving her to think of her father at every intimate entry of a man in her life. It feels grotesque to see it spelt out on the pages of a book that reads like the experience of stumbling through Anna’s stream of consciousness. It’s the intriguing women in Anna’s life who shape her being –– her mother, her friend Sujata who is often inflicted with thoughts of suicide and Jessie, the beautician at Bollywood Style Salon. The men come and go, with their philandering ways in this motley mix of sisterhood. “She’s raised me to be liberal, but Mummy’s mouth is so cruel about Daddy’s new family, that the boundaries of acceptance have blurred within me,” Carvalho writes. These blurred boundaries in Anna’s life contribute to her debilitating sense of hope. Her search may continue but her heart aches with every encounter. “We belong to the sisterhood of swans, seeking to pair for life, curving our necks to entwine with the perfect mate. Only seldom we find them,” she believes.

The crux of the novel remains Anna’s evolving relationship with her father and the memories she has of him. Never venturing to meet him for almost a decade, she runs into his stepson at her work. Both children are products of similar treatment and yet their worldviews vary vastly. Her exploration of this distance and kinship is portrayed beautifully in this text.

Selma Carvalho is a British-Indian writer who explores themes like migration, feminism and morality in her works. She has previously written three non-fiction books on Goan presence in colonial East Africa. Her writing has often been shortlisted for awards like London Short Story Prize, the Dinesh Allirajah Prize and New Asian Writing Prize. This is her debut fiction novel that digs its talons deep into your psyche and makes you question memory and the ways we internalise moments. The impact of her book is as deep as those memories that come back even after decades.