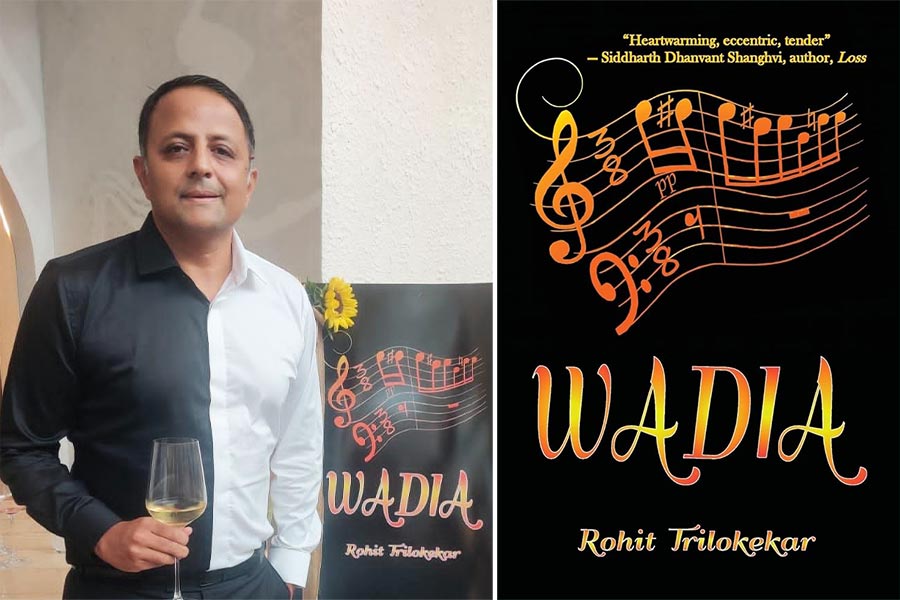

Rohit Trilokekar’s latest novel, Wadia (1889 Books), is an interestingly titled book that leaves you pondering its significance until the very end. While it may initially present itself as a mystery thriller, to a discerning reader it becomes much more, unravelling in the mind long after it ends on the page.

It’s a deeply moving story of discovering one’s self, or a bildungsroman. The story follows Wadia, the scion of a wealthy Parsi family who, for much of his life, has had no profession to speak of. He is alone, having lost his parents long ago and never married. He lives in a grand bungalow, envied by his ‘cattolic’ neighbours who refer to it as the “white house”.

The first few chapters detail Wadia’s life and help to set the story in place and time. The opening chapter meticulously outlines Rustom Wadia’s daily habits — reading Homer’s Iliad with his inability to understand certain passages, reminiscing about his deceased parents and pets (Polly and Fluffy, the focus of Trilokekar’s previous novel, The Perfect Outside), and enjoying the occasional whisky and his customary cognac after dinner. These habits, though seemingly eccentric and self-indulgent, are nevertheless interesting, and establish Wadia as a character who doesn’t get along with the outside world much.

The novel displays tongue-in-cheek humour mostly through the persona of its protagonist

Wadia’s quiet and unhappening life is overturned when he decides to look for information about his family. Suddenly, he feels an urgent need to uncover the story of his grandfather, who was adopted by a wealthy Parsi gentleman and given his surname. Questions of identity are thrown up in the initial chapters, making the reader reflect on what is often taken for granted.

The first third of the novel carefully lays out the various relationships, friendships and habits of Wadia, making him feel like someone you might have met during your sojourns in Mumbai. The novel displays tongue-in-cheek humour mostly through the persona of its protagonist, something that Trilokekar has mastered through his fiction and columns over the years.

It is a geriatric’s world on display here, a perspective not often found in Indian English fiction, and Trilokekar deserves commendation for this. The novel probes into how the elderly manage their worlds and navigate the unknown without giving into grandstanding. Much of the book covers Wadia’s physical journey along with Toral Shah — a Gujarati girl he befriends, who runs a restaurant in Bandra West and is related to him. There’s also Arun Velkar, a Maharashtrian friend of Wadia’s of many years.

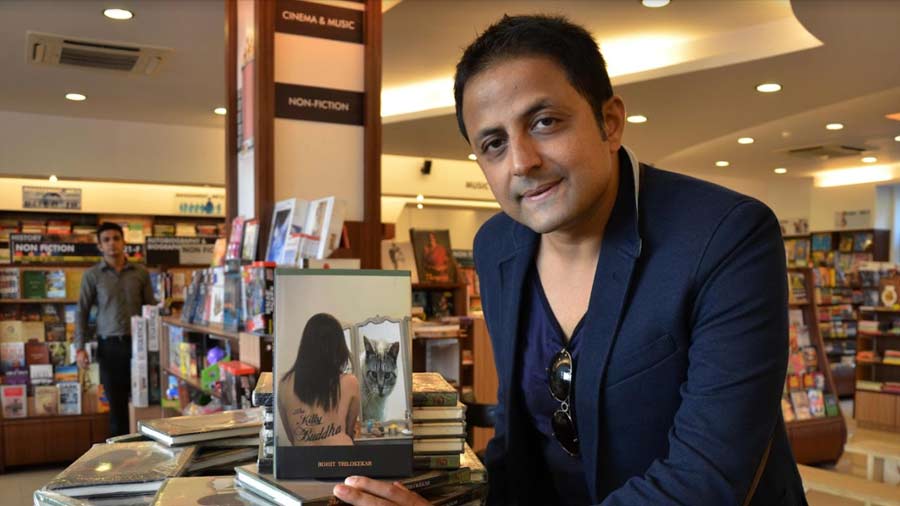

Wadia finds it difficult to navigate modern Mumbai just as he struggles to negotiate relationships. Initially, he does not come across as a lovable character, but as the novel progresses and Trilokekar delves deeper, Wadia emerges as layered and more compelling. Trilokekar, whose previous protagonists have been animals (as part of charming allegories), paints Wadia mostly in grey, making the reader an active participant instead of a passive observer in understanding the moods and motivations of a man who ambles through life in a city where most others are scampering for breath.

The ending comes as a bit of a surprise, revealing Wadia’s deep connection to Beethoven

‘Wadia’ captures many of the subtleties of Mumbai that often escape the popular imagination TT archives

At the outset, the world explored in the book is not a happy one — Arun and Vidya Velankar are childless, Wadia is bereft of company and the loneliness hits him hard. Notes of disease, death and decay permeate the novel. Toral, though young and cheerful, is an orphan who has her moments of sadness as well. The book addresses the challenges of living in a rapidly changing world, evidenced by Wadia’s quotidian problems to find a taxi or an auto, and his reluctance to leave the comforts of his home after 10 long years.

However, the novel concludes on a hopeful note — Wadia finds companionship with Jasmine, who had known his aunt, Elise, in happier times; Anil and Vidya Velankar express their desire to adopt Toral as their daughter and she accepts. Elise’s ghostly presence — not unlike that of Estella in the life of Pip in Great Expectations — finally melts into peace for Wadia. The ending comes as a bit of a surprise, revealing Wadia’s deep connection to Beethoven’s Fur Elise — a piece mentioned innocuously in nearly every chapter — and his ability to play the piano, as if possessed.

The city of Mumbai, particularly the area of Bandra, finds a lot of prominence in the novel, as does the rich Parsi culture. In a city where identities can quickly blur, the themes of legacy and love blend neatly to make Wadia a breezy yet contemplative read.

Devapriya Sanyal is an assistant professor of English at St. Joseph’s University, Bengaluru. When she is not teaching, she loves writing, watching world cinema or travelling.