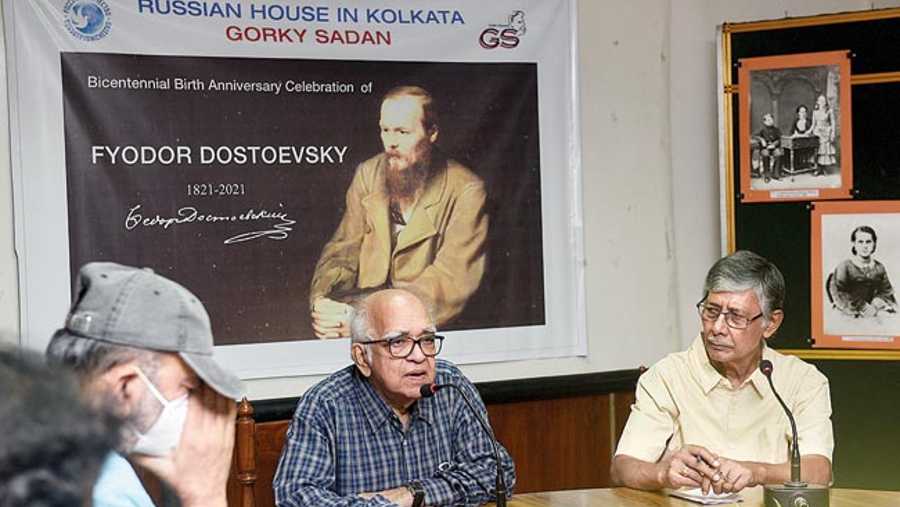

Conflicts and complexities marked both the life and the writings of Fyodor Dostoevsky, whose bicentenary birth anniversary celebration was organised at Gorky Sadan recently by Friends of Latin America and Eisenstein Cine Club. On the concluding day, on November 19, Samik Bandyopadhyay, eminent literary and art critic and chief coordinator of the cine club, spoke of the Russian author who has given us classics like Crime and Punishment, The Idiot and The Brothers Karamazov.

None of them would have materialised if the Czar’s pardon came a bit later for a young man on death row who was all set to be shot at behind prison bars.

Bandyopadhyay took the audience back to Dostoevsky’s family background and formative years to explain the contradictions in his life. Dostoevsky, he said, was born in 1821 in an aristocratic family in a society where pockets of affluence existed in the midst of widespread impoverishment and deprivation. “He suffered from a guilt complex which made him rebellious. He blew the money in hand when he went for studies and took to gambling to pay off his debts. His lifestyle was disintegrating from an early age.”

When he was 18, he wrote to his brother that he had read up Honore de Balzac, William Shakespeare and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in their entirety in the space of just one year. “This was an expression of his determination not to leave any gaps.” He also translated Balzac’s novel Eugenie Grandet while he was in his 20s. “This may be considered his first literary work.”

At the start of the 19th century, the foundation of the Industrial Revolution was being laid with the English, the Dutch, the Italians, the Danish, the French, the Belgians and the Portuguese were spreading out across the globe to set up colonies and amass wealth through trade. The wealth would fuel the revolution.

“The Russians did not join this colonisation race but through French literature, especially Balzac, Dostoevsky got a taste of history unfolding, which must have triggered a turmoil in him.”

Illustrations of characters from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s works sent by the Dostoevsky Museum in St Petersburg being coloured at an exhibition at Gorky Sadan which concluded on Friday

He faced another conflict when his family forced him to join the army, in the engineering wing. “A man with such sensibilities joining the army meant being trapped in the rigours of regimented life. He would quit after a while but by then his outlook had become more complex.”

He would soon join a circle that dreamt of a utopian society, but at a surface level. Within a few years, he was arrested for treason and sentenced to death. “Yet, he never got involved in any political agitation.” On the appointed day, all the rituals that are followed before execution were over. It was just a matter of minutes before the trigger would be pulled when dramatically the Czar’s pardon was read out. His sentence was reduced to eight years imprisonment, which later got reduced to four.

“He still had to go through the harrowing experience which he described to his brother. His conflicts never took a political path. Yet inwardly he was becoming more complex.”

The London years

He travelled to London on his release from prison. Bandyopadhyay speaks of another letter to his brother where he writes of London streets — factory hands sucked dry at the shift’s end, prostitutes soliciting, and a girl in rags moving listlessly. “Dostoevsky is moved to give her some money, which the girl grabs and runs away. ‘She was scared that I might snatch it back,’ he writes.” Moderator Gautam Ghosh, the events coordinator at Gorky Sadan, would later add that the author had contemplated suicide that night.

A few years ago, in 1851, the Great Exhibition of the Industrial Revolution had taken place over months showcasing every marvel of the Victorian Age from Britain or its colonies. “Technological innovations were placed side by side with naked African slaves in chains. Though the exhibition was long over, people were still talking about it when Dostoevsky landed there in 1854. He felt nothing but dismay at the reports.”

Charles Dickens was then writing on life in industrial England. Friedrich Engels too quoted from Dickens’s novels in his study titled The Condition of the Working Class in England. “Dickens used to hold ticketed reading sessions to make a living, which used to be frequented by the neoliterate working class. He did the reading so passionately that sometimes he would faint. We do not know if they met but Dostoevsky read up Dickens and wrote a commentary on The Old Curiosity Shop in Russian.”

When he returned to his country, he could not settle down, riddled as he was with debts. At the fag end of his life, he wrote his masterpieces. The Brothers Karamazov was published barely four months before his death in 1880. “The entire consciousness of a criminal does not get embroiled in criminality. He remains conscious of committing the crime. There is always a distance from his conscience. This distance and the accompanying pain becomes the subject of Dostoevsky’s maturest work,” Bandyopadhyay summed up.

On celluloid

The lecture was followed by the screening of White Nights directed by Luchino Visconti, based on a short story by Dostoevsky.

Ghosh pointed out that as many as 228 films have got made across the world on Dostoyevsky’s works. “We are trying to get access to as many of them as possible and screen them in the course of this bicentenary year. His wife Anna was a mainstay of his life, who even handled the publication of his works. We wanted to screen a film on their relationship called 26 Days in the Life of Dostoevsky, by Aleksandr Zarkhi. NFDC had bought a copy but we could not trace it. In Bengal too, a film called Aparichito was made, based on Samaresh Basu’s novel which had overtones of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot,” he said.

Shades of the author

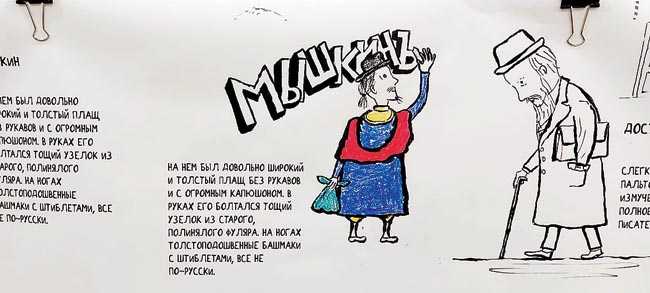

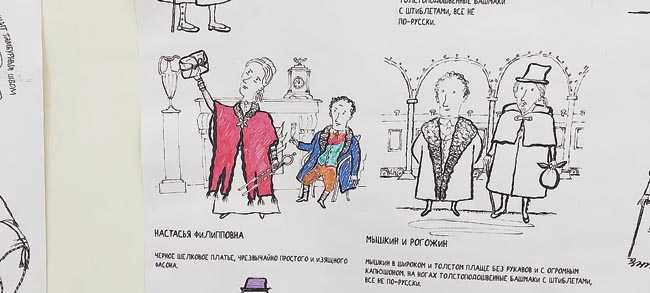

A week-long exhibition on Fyodor Dostoevsky’s world was hosted by Gorky Sadan as a start to the bicentennial of the author’s birth anniversary. It comprised colouring pages with sketches of characters from his works drawn by artists Nika Velegzhaninova and Igor Knyazev and was part of a travelling exhibition called Colouring Dostoevsky by the St. Petersburg Dostoevsky Museum, housed in a building where the author spent his final years.

According to museum sources, Dostoevsky’s world is usually imagined in subdued, sombre grayish-brown tones, but his works are full of colour. “Dostoevsky’s St Petersburg isn’t always dreary, and his characters wear clothes that are often bright and colorful, in line with fashion and the times. Paying serious attention to costume, Dostoevsky gave detailed descriptions of his characters’ clothing, often singling out a particular detail (Raskolnikov’s hat and Sonya’s kerchief in Crime and Punishment, Myshkin’s raincoat in The Idiot).

A sketch of Prince Myshkin from The Idiot at the exhibition

Dostoevsky’s characters coloured by visitors to the exhibition

Dresses worn by Dostoevsky’s characters

“Dostoevsky himself was very picky about his wardrobe and went to the best tailors. He loved expensive clothes and kept up with the latest trends in fashion. Sometimes he imbued his literary characters with his own tastes (Raskolnikov wore out a coat from Sharmer, Dostoevsky’s tailor; Myshkin wore a jacket similar to one of Dostoevsky’s; etc.),” an official note from the museum says.

“The exhibition gave visitors the opportunity for participation in a different way from how we view his texts. They got a better idea of Dostoevsky’s habits and his characters’ tastes. The captions were in Russian this time but we plan to ask the museum for English translations,” said Irina Malysheva of Gorky Sadan.