Almost over a decade and more ago, Balaji Vittal met me with his proposal for a book on RD Burman (co-authored with Anirudha Bhattacharjee). The first thing that struck me about him was an unbridled enthusiasm for the subject matter. Something that translated into the written proposal and first draft that they submitted. I was bowled over by the research and the material they had put together. An embarrassment of riches. Everything but the kitchen sink, so to say (and I mean it in an entirely complimentary sense). Navigating the edits of that book, the toughest call was what to leave out for the sake of crispness without sacrificing the delectable trivia and information the text had.

Author Balaji Vittal by the Howrah Bridge, on New Year’s Eve, 2021 @vittalbalaji/Twitter

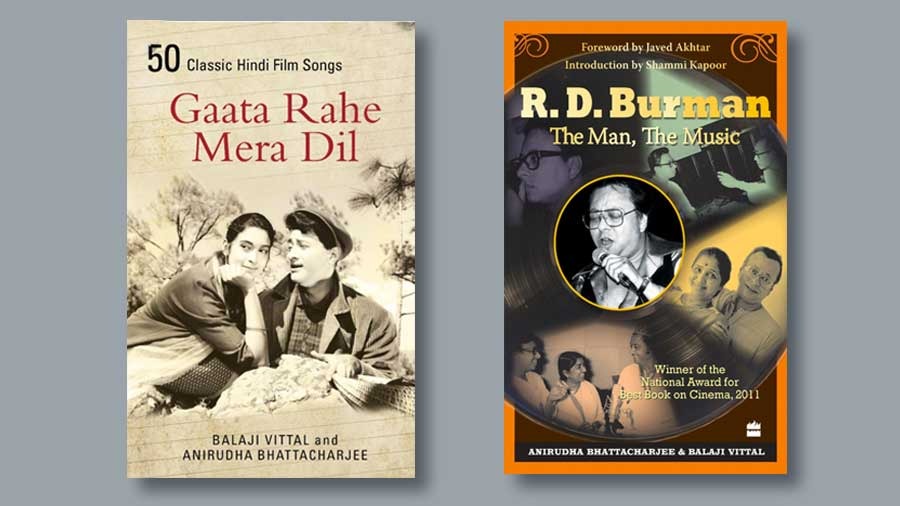

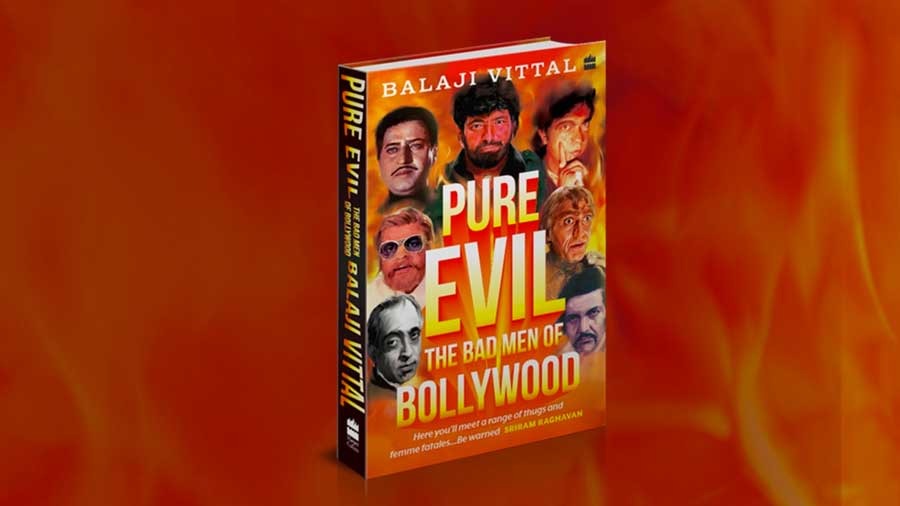

I mention this because his latest book, Pure Evil: The Bad Men of Bollywood, comes with a similar exacting focus on information that accentuates the reading pleasure. In fact, so impressive was their effort on RD Burman (it eventually fetched them the National Award for Best Book on Cinema), that even before the book was done, I had offered them two more contracts. Their second book, Gaata Rahe Mera Dil: 50 Classic Hindi Film Songs, marked by the same rigorous research and accent on information, went on to win the inaugural MAMI Award for Best Writing on Cinema.

Pure Evil is the third book in that series of three we signed in the wake of the RD proposal. In between, the duo collaborated on a well-received biography of SD Burman. Though Balaji has gone on his own with Pure Evil (while Aniruddha has done the same with his forthcoming book on Kishore Kumar), for me as a reader it is rather impossible to consider either author without the hyphen in between – and that extends to the richness of the material in Pure Evil too.

Like RD Burman: The Man The Music, which will remain the definitive book on the legendary composer, and Gaata Rahe Mera Dil, which despite the herculean task of selecting 50 out of lakhs of Hindi film songs is probably a decisive take on the subject, Pure Evil is unarguably the most authoritative look at villains in Hindi cinema. Given the breadth of his research and the information and analysis that inform Balaji’s take on the bad men (and women) of Bollywood (that’s a bit of a misnomer, because a large part of the fun villains in Hindi cinema came before it became Bollywood).

It is the villain who makes a film come alive, from the name to the sartorial taste to the hideout

'Pure Evil' is pure fun for its content and the author’s research into the subject

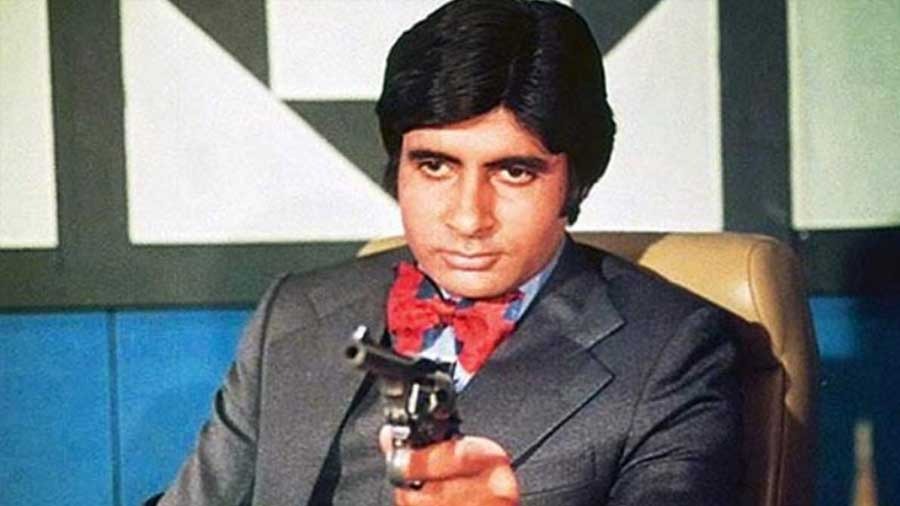

It goes without saying that our heroes are heroes because of the villains they overcome. Imagine Sholay (1975) without Gabbar Singh or Mr India (1987) without Mogambo. It is the villain who makes a film come alive and this is reflected right from the names they are endowed with to their sartorial tastes and their hideouts (particularly in the Bombay cinema of the 1970s and ’80s) which beat the staid lifestyle of the heroes hollow. I for one wouldn’t mind exchanging the modest homes of many of our heroes with the dens that Sher ‘Shera’ Singh (Amrish Puri, in Loha, 1987) or Shakaal (Kulbhushan Kharbanda, in Shaan, 1980) inhabited. And then there are the lines they get to spout; which hero has ever got a line like Ranjeet’s in Subhash Ghai’s Vishwanath: ‘Once in a blue moon, kabhi kabhi…’? I dare say, among the heroes of Hindi cinema only Amitabh Bachchan has had lines as memorable as the ones those playing the villains got to deliver (and even Bachchan’s best lines came as the antihero).

Amrish Puri as Sher ‘Shera’ Singh, in ‘Loha’ (1987) and Kulbhushan Kharbanda as Shakaal, in ‘Shaan’ (1980)

This is something that Balaji recognises at the outset in the introduction and proceeds to create a memorable and hugely enjoyable portrait of the villain in Hindi cinema. Just look at the Contents and you get an idea of the spread he has in store: from the colonisers and the foreign hand in ‘Mera Bharat Mahaan’ to the megalomaniacs, zealots and bigots in ‘Pagla Kahin Ka’ to one on the various shades of the outlaw (the hoary dacoit of the ’60s and ’70s and their offspring), the gangsters and mafia which came into its own with Ram Gopal Varma’s Satya (1998).

Manoj Bajpayee and J. D. Chakravarthy in Ram Gopal Varma’s ‘Satya’ (1998)

In the process he also provides a snapshot of the socio-economic and political churn of the nation over 75 years of our Independence. The changing face of the villain in our cinema in many ways reflects how we have changed as a nation. It was unthinkable in the 1950s to imagine a politician as a villain. By the 1980s, they were at the top of the rung as on-screen rogues. Or the relatively ‘docile’ dacoits of Jis Desh Mein Ganga Behti Hai (1960) and Mujhe Jeene Do (1963) metamorphosing into the terrorists, land mafia sharks and white-collar criminals of more recent vintage. Balaji’s book covers it all.

Pran as dacoit Raka in ‘Jis Desh Main Ganga Behti Hai’ (1960)

Parts of 'Don' were shot in Waheeda Rehman’s residence!

What sets the book apart is the attention to minutiae, making it a film-buff’s delight. So, while we get the lowdown on the greatest and most memorable of the baddies, information on which is readily available, Balaji never forgets the smaller picture.

Consider, for example, Chandra Barot’s 1978 blockbuster Don. While providing us with the evolution of the ‘Don figure’ in Hindi cinema, as an aside we also get to know that the film took close to five years to complete because the filmmakers were all broke! Parts of the film were shot in Waheeda Rehman’s residence and the makers also ‘piggybacked’ on standing sets of other films. And then there’s Manoj Kumar’s priceless comment on the film’s title as narrated by the director. Just the kind of digression that enlivens the reading experience.

Amitabh Bachchan in Chandra Barot’s 1978 blockbuster 'Don'

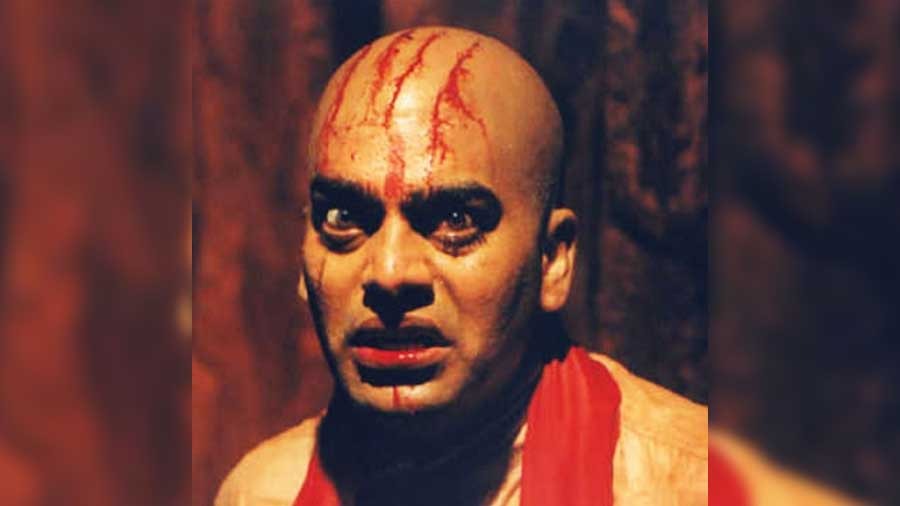

Or Ranjeet’s hilarious account of shooting for Mastan Dada in a taxi while on a six-hour stopover at Bombay on the way to London from Mauritius, ending up also shooting for Haath Ki Safai in the process (the filmmakers managed to get him out of immigration for those few hours to enable him to shoot!). Or the links that the author makes between black magic and the occult in films dealing with serial killers (from the high priest in 1934’s Amrit Manthan to Ashutosh Rana’s frightening rendition of Lajja Shankar Pandey in 1999’s Sangharsh).

Ashutosh Rana as Lajja Shankar Pandey in 1999’s 'Sangharsh'

The book overflows with similar trivia and interviews with a wide cast of characters that provide a glimpse not only into the history of the villain in Hindi cinema but also the madness of moviemaking.

Despite its editorial and proofing flaws (I gave up making notes after six typos in the first 43 pages), Pure Evil is pure fun for its content and the author’s research into the subject. As one of the greatest villains of Hindi cinema would have said, ‘Mogambo… khush hua.’

#PureEvil by @vittalbalaji is a riveting account of all the villains in Bollywood's cinematic history that redefined what it takes to become the "Bad Man" of Bollywood. Order now: https://t.co/JWMnmUt6xQ pic.twitter.com/qf9aDZLP3v

— HarperCollins India (@HarperCollinsIN) December 18, 2021

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is a publisher, editor and critic. An avid film buff, he loves poetry and music.