In a landmark online sale at UK auctioneers Lyon & Turnbull on June 12, prices went wild for 68 rarely seen Indian pictures and a few craft pieces that belonged to the trailblazing mid-20th century collector-scholars William and Mildred Archer. Not only were they among the first people to identify and write about a number of areas of Indian art, such as Mithali folk art and Pahari court paintings; this was one of the few remaining private collections of Indian art made in the mid-20th century to come on the open market. With a detailed catalogue written by Andrew Topsfield, former Keeper of Eastern Art at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford – and student and friend of the Archers – the sale marks a new chapter in the increasing appreciation of the breadth of Indian art in the global collecting market.

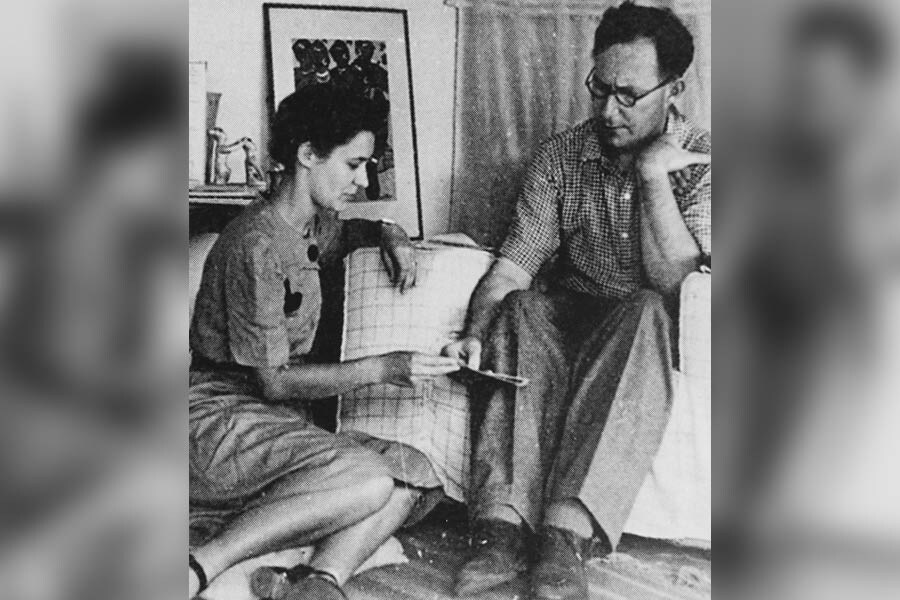

This is especially true of India’s exceptionally vibrant popular art, which still thrives today. It was this that Bill and Tim Archer, as they were known, came across and instantly appreciated while they lived in India. Bill (1907-79) went there in 1931 aged 24, posted to rural Bengal by the Indian Civil Service. He returned to Britain three years later to marry his teenage sweetheart, Tim (1911-2005), and they both then lived in India until 1948. With deep curiosity about their host country, they paid sharp attention to religious sculpture and rural culture – in particular its art, language and poetry. Bill’s first book, The Blue Grove, was a translation of Uraon folk songs; Tim taught in local schools and amended school text books.

Trailblazing collector-scholars Mildred and William Archer

The Archers were struck by the contemporariness of popular Indian art and how it related to modern Western art; in 1959, Bill would work with the art historian Herbert Read on the cutting-edge exhibition ‘40,000 Years of Modern Art: A comparison of Primitive and Modern’ held at the ICA, London. More recently, Jyotindra Jain championed it at the worldwide festivals of India held in the ’80s and created Delhi’s National Crafts Museum, while OP Jain sent a bevy of people throughout India to buy everyday art and objects before founding Sanskriti. Trailblazing collectors Lekha and Anupam Poddar brilliantly dubbed it ‘the other contemporary’. Kolkata-raised Anupam Poddar does not even make a distinction between popular and high Indian art in his MAP museum opened last year in Bangalore; it is simply good art made in India.

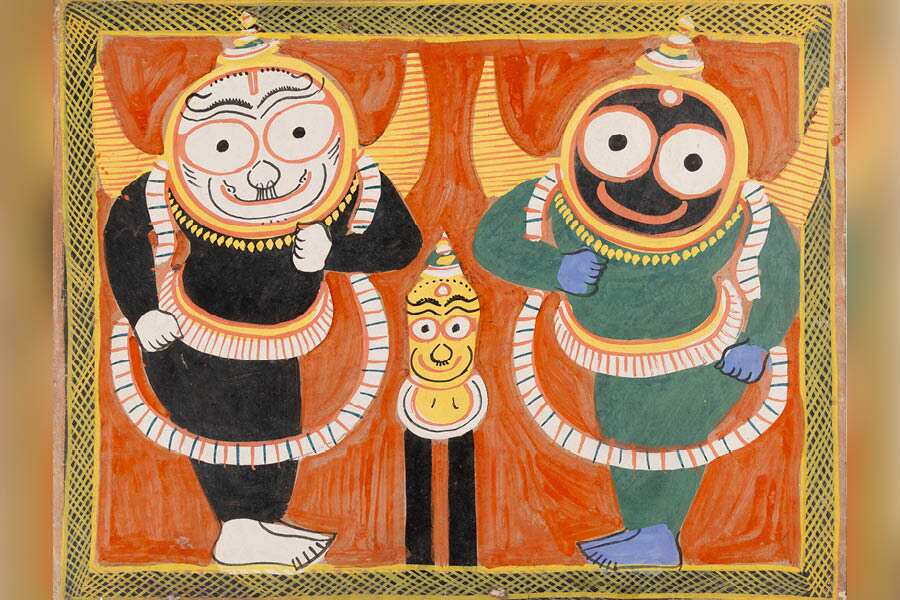

At the Archer auction, it was as if ‘the other contemporary’ had gone viral. The first six lots were bazaar paintings of Jagannath, his brother Balbhadra and his little sister Subhadra. William Archer bought them in the early 1930s outside the Jagannath temple in Puri, Odisha – as pilgrims might pick up similar mementoes today. Bold, full-frontal icons with huge, circular, staring eyes, they are slightly unnerving. But not to buyers at the sale, who bid up the first lot from a cautious estimate of £400-£600 to a sale price of £2,016. It set the tone for the whole sale.

The Jagannath Trio. William Archer bought this in the early 1930s outside the Jagannath temple in Puri, Odisha

Next to come under the hammer were some Mithila paintings, each depicting a bride on rough paper in mostly pinks and yellows. Produced by the Maithil Kayasth community in rural Bihar, these were used as composition aids by women decorating special marriage chambers with murals to promote prosperity and fertility for the bride and groom – today, women continue to decorate their homes with new murals after the monsoon. The five paintings on sale were bought by Archer in 1934, when he noted with remarkable prescience that the murals portrayed women ‘with a shrill boldness, with savage forcefulness… Not for them the frail and whimsical fancies of a floating world… Here was Picasso naked and unashamed.’ Proving he was on target almost a century ago, one painting he found in Darema village sold for £1,638 (estimate £300-£500). Even if the Archer association pushed up the price, this art is now in the public eye and deserves to maintain, even increase, its price tag.

Each Mithila painting depicts a bride on rough paper in mostly pinks and yellows

A splendidly powerful illustration to the Mahabharata – showing Harishchandra and his minister killing an enormous tiger whose claws seem to scratch the picture frame – soared through its estimate of £1,000-£2,000 to sell for £10,710. Until recently, its provenance would confidently be given as Paithan, Maharashtra, mainly because the great Pune collector Dinkar G Kelkar’s father-in-law was given eight hundred of these paintings as part payment from a client living in Paithan. A good enough reason. However, new research by Anna Dallapiccola reveals that those pictures (and therefore this one too) were made in Pinguli on the Maharashtran coast, a town still practicing its distinctive puppetry, theatre, storytelling and painting.

It was when Bill was re-posted to Patna city in the early ’40s that he and Tim met the local intelligentsia who opened their minds to the refined court paintings of the Pahari Hills and other schools of classical Indian painting. Their growing passion for all Indian art led to lasting friendships with Indian academics and collectors such as Karl Khandalavala, Gopi Krishna Kanoria, Rai Krishna Das, MS Randhawa, as well as the younger BN Goswamy and Chhote Bharany who have only recently passed away, and Jagdish Mittal who celebrates his centenary next year. The Archers were part of this pioneering group – for instance, Das had already established Varanasi’s Bharat Kala Bhavan in 1920, Bharany gave his collection to Delhi’s National Museum, Mittal is hoping to create a museum of his tip top collection in Hyderabad.

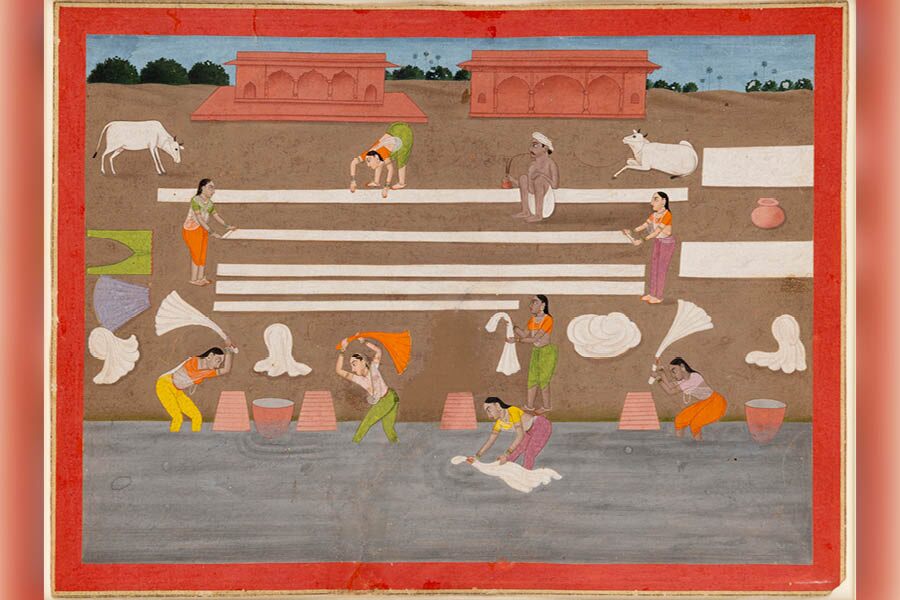

The washerman and his women – Murshidabad, Bengal, circa 1790

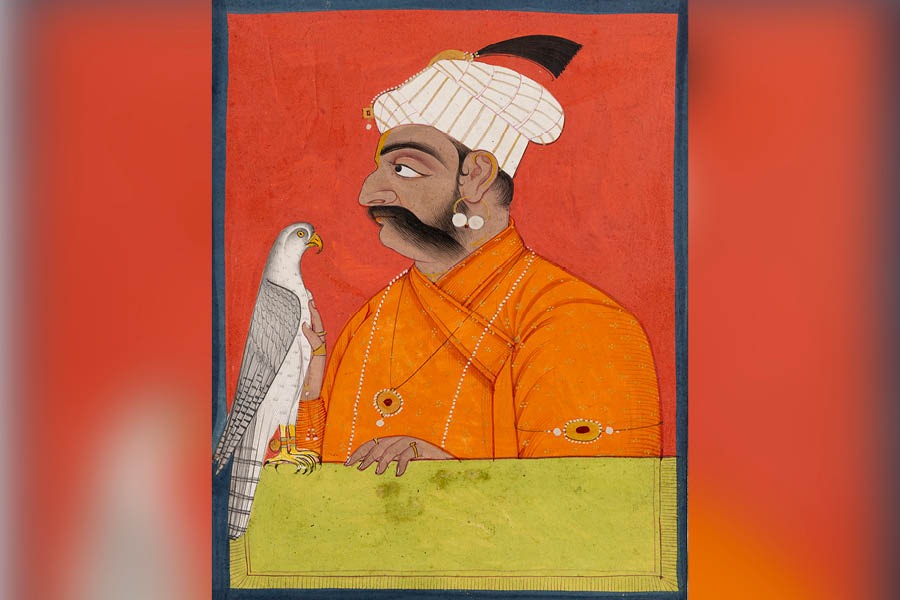

The sale’s group of high-quality Pahari paintings, including early vibrant gems made at the Nurpur and Kulu courts and a later, soft-palette royal scene from Jammu, rocketed to expected high prices given their established place in art history and the saleroom – but their low estimates must have left some potential buyers disappointed. Similarly, two well-preserved early illustrations to the Ramayana made around 1630 in Malwa, in present day Madhya Pradesh, each sold at over £11,000 from estimates of £2,000-£3,000. Less easy to estimate were a couple of quirky townscapes made in Jaipur around 1780, which tickled enough buyers to bid them up to fetch more than £20,000 apiece, while an almost abstract washing scene made at Murshidabad around the same soared to £43,951 (estimate £3,000-£5,000). The saleroom experts put part of these remarkable figures down to ‘the romance and respect for the Archer factor’. Don’t expect them to set the new norm.

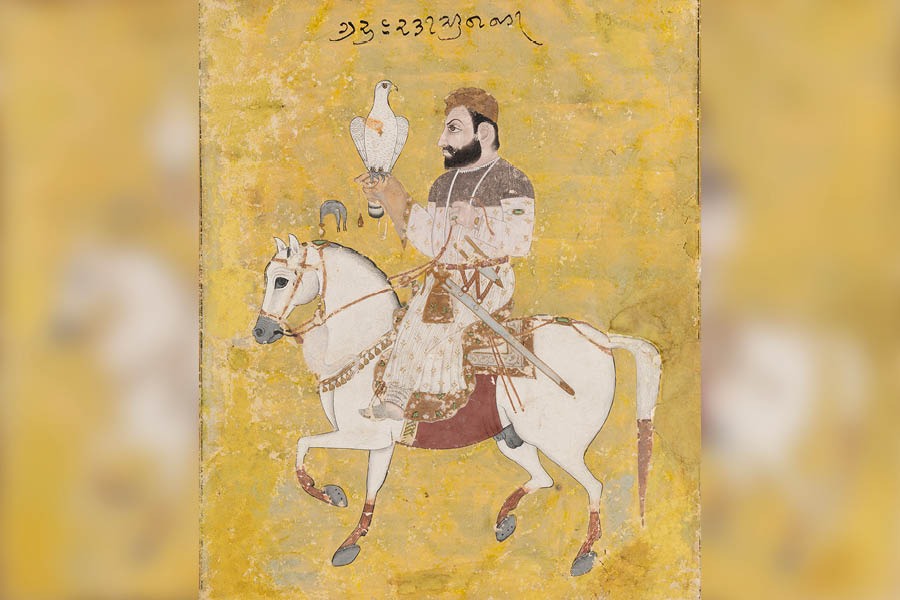

Raja Suraj Mal of Nurpur holding a hawk, circa 1770-80

On their return to London, Bill was appointed Keeper of the Indian Section of the Victoria & Albert Museum and simultaneously wrote the seminal survey of these Pahari court styles, while Tim put order into the India Office Library’s rich and unwieldy collection of paintings. Both of them encouraged the next generation of academics and collectors, such as Howard Hodgkin (much of whose collection is now at the Met in New York) and Edwin Binney 3rd (whose collection is at San Diego Museum of Art).

Above and way beyond all this, the prices made by two lots towards the end of the sale astonished everyone. An exquisite domestic scene centred on an elegant European lady reclining on her divan, made in Gujarat’s major port of Surat around 1740, sold for £175,201 (estimate £20,000-£30,000) – it would be intriguing to know who snapped up this masterpiece. The sale’s penultimate lot was a sensitive equestrian portrait of the cultured sixth Sikh guru, Hargobind (1595-1644), made in Jammu state around 1700, which defied its £3,000-£5,000 estimate to go under the hammer for £156,451, making clear both the importance of big exhibitions about Sikh art at the V&A in 1999 and at the Wallace Collection this year, and the buying power of new-generation Sikh collectors.

An equestrian portrait of the sixth Sikh guru, Hargobind

As the auction was online, the thrill of the auction room was absent. So, too, was seeing who was buying what. Let’s hope some of the Archer treasures have been snapped up by museums around the world and will be studied, catalogued and displayed for the public to enjoy – and to remind us of what great collecting is about.

[Those interested in the sale catalogue can view it here; sale results can be viewed here.]