You are a dedicated and committed warrior and have ticked all the right boxes in strength and conditioning over the years. You have seen and experienced major changes in your health and fitness but recently have been a little worried about the ‘gains’ not being in the right proportion to the effort that you put in. By ‘gains’, I don’t necessarily mean the size and shape of your muscles but getting faster in your sprints, increasing cardiovascular and muscular strength, your ability to generate more power, and so on. You seem to have hit a training plateau where the body gets used to the training regimen and while your regular routine is helping you to maintain your health, they are not really leading to better performance.

If this is the case, now is the perfect time to shift gears. You need to reorient your goals to set some “personal bests” — introduce an added motivation and excitement for both your body and mind and feel the joy of conquering new heights.

Many years ago, I had run into a wall where my fitness was concerned. An auto-immune dysfunction, joint pain and a bad knee injury had seemed to put a spoke in the wheels. I decided to shake off the deterrents and set myself three goals. While the goal was a big driving factor, it was the journey and process that shook up my body and set me back on track. I set myself three goals:

- Break the four-minute barrier in a 1km run

- Improve my vertical jump score

- Improve my pull-up score

You too can take yourself to the next level by using my guidelines to cross these barriers.

Breaking the four-minute barrier on a 1km run

It is a part of athletic folklore how former English athlete Roger Bannister broke the four-minute a mile (around 1.6km) barrier, but most of us lesser mortals would be happy to run a kilometre in under four minutes.

Find a track and take a time trial for a kilometre. Try to run at a comfortable but fast pace (or “tempo”), not start flat-out and then crawl for the last 200m. Record the timing. Calculate the race-pace or how much you run in a minute, by dividing 1km by the total time taken. If, for instance, it takes you four-and-a-half minutes for a kilometre, then your average one-minute speed is (1,000/270)x60 or 222m.

To beat the four-minute barrier, I needed to run 250m in under one minute and repeat it four times over the length of four minutes. I could, at the time of starting, run around 260-265m in a minute but my conditioning was not great enough to keep up the tempo over four minutes. The protocol I designed for myself was simple.

Week1-3: Run four individual 250m intervals. Record the time for each such interval. Start by giving yourself two minutes rest between intervals but gradually reduce it to 60-75 seconds by the end of the third week. By the end of three weeks, you should be able to run all the intervals in under 60 seconds.

Weeks four-six: Run 500m in under 110 seconds, rest two minutes then run 250m twice at the intended race pace of 54 seconds with a rest of one minute between them.

Weeks seven-eight: Run 500m twice with a rest of two minutes between them. I was able to clock 110 seconds for each. In other words, by now, I had managed to run a km in 220 seconds or three minutes, 40 seconds. Now, all that was left was piecing the two 500m intervals together. When attempting a full kilometre run, you are expected to lose another 10 per cent or around 20 seconds more (factor that in).

Week nine: Take the time trial. Yes. You want to buy drinks today for all your running buddies. You have just conquered the under four-minute kilometre. Incidentally, I clocked 3.50 after giving myself an eight-week window of preparation.

Improving your pull-up score

When it comes to breaking training plateaus, pull-ups offer one of the hardest resistance. More than the bench press or the push-up, I like to regard the pull-up as the gold standard of upper body strength. It’s one of those exercises that seem very hard when you are a beginner, quickly becoming easier and easier, but then you hit your maximum rep limit pretty soon. After that sticking point, it gets very tough to improve further. For example, the US Marine Corps fitness test consists of pull-ups, crunches, and a three-mile run. While the maximum score for crunches is obtained when you do 100 reps, the maximum score for pull-ups is set at 20 reps.

Attach a band as demonstrated and then do as many reps as possible. For example, if your max is eight, then continue with the help of the band after your eighth rep up to the point of failure

Get yourself good resistance bands

Step1: Attach a band as demonstrated; then do as many reps as it takes after your main set. For example, if your max is eight, then continue with the help of the band after your eighth rep up to the point of failure. Note down the number of reps and work three-four sets. You should be able to add one extra rep a week. In three-four weeks’ time, subjects are typically able to add at least one or two more reps to their unassisted pull-up score.

Step 2: After three-four weeks of banded assistance, use a small block to jump up and hang from the rod. Lower yourself down slowly controlling the descent with good form. Work till failure. Continue doing this for three-four weeks. Test yourself after that — you will get a pleasant surprise.

Increasing the vertical jump height

The vertical jump is the gold standard test for explosive power in the legs. How high you can jump reflects the power in the fast-twitch fibres of the leg muscles.

Test your vertical jump. Refer to www.topendsports.com/testing/norms/vertical-jump.htm for the protocol. Note down the score, then spend the next six weeks training to better the score. These two exercises will help you to reach the target.

The box jump is a plyometric exercise that adds explosive power in the legs and hips

Box jump: Start with a 24-inch jump, and graduate to a 36-inch box in three-four weeks. Box jump is a plyometric exercise which quickly helps to add explosive strength in your hips and legs. A plyometric exercise makes use of the body’s involuntary nervous system reflexes to produce a huge muscle contraction, so when you jump on to the box, you should be launching yourself up the moment you land. First practise to get your form right — you should be landing on the balls of your feet, as softly as possible on the top of the box in the squat position. Step off the back, as softly as possible, with a slight bend in your knees to absorb the pressure, and jump up immediately.

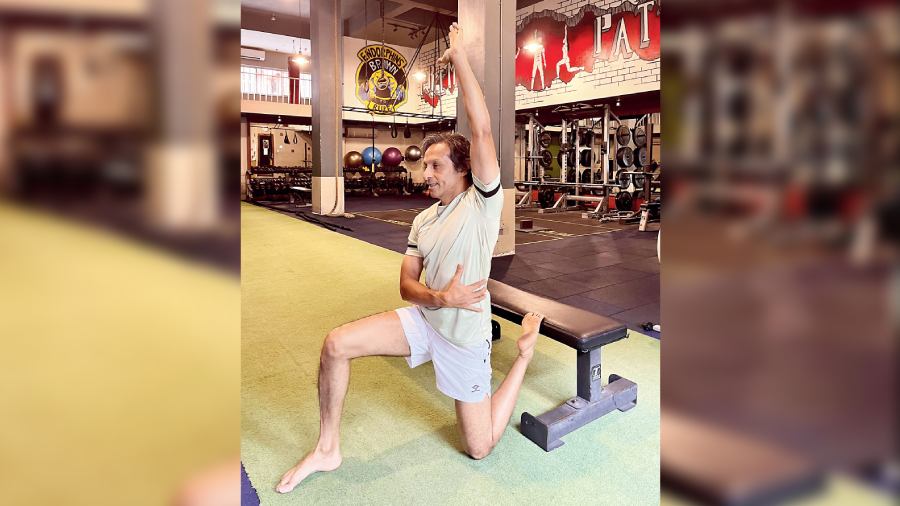

When the hip flexor muscles get facilitated, it decreases the power in our hip extensors

Hip-flexor bench stretch: We spend a disproportionate amount of time sitting every day and this plays havoc with the length of our hip flexors. When the hip flexor muscles get facilitated, it decreases the power in our hip extensors. Stretch the hip flexor muscles with the help of a bench every day (as demonstrated) to augment the hip drive and generate more power in the vertical jump.

Swiss ball leg curls: Lie supine with your feet on top of a Swiss ball and curl them in till the toes rise up and the hips are in full extension. Return to the starting position. This is one repetition. Do three sets and repeat 10 times each. A Swiss ball curl helps to strengthen the posterior chain extension mechanism in the hamstrings and glutes, making it possible to produce explosive strength along that chain of muscles.

Ranadeep Moitra is a strength and conditioning specialist and corrective exercise coach.