In 2021, smack in the middle of the pandemic and a life-threatening illness, I joked saying I only kept at my English degree to understand Hozier’s music.

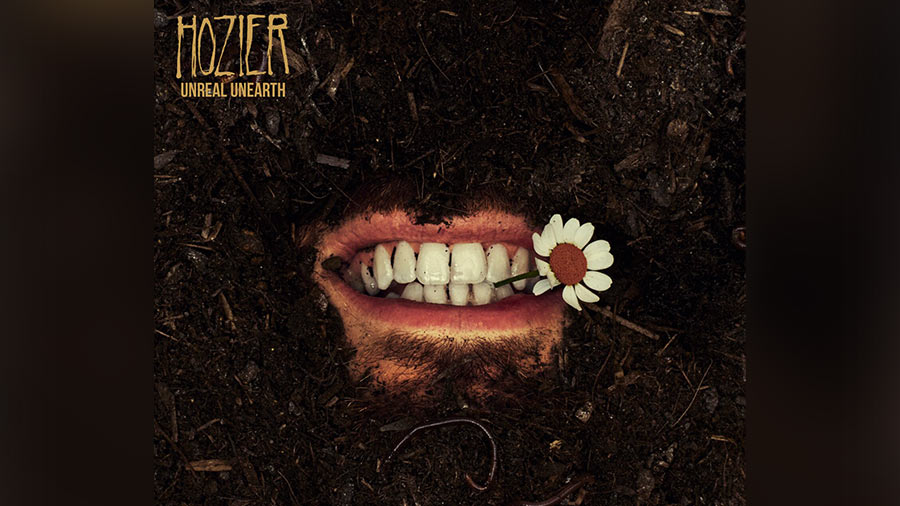

Unreal Unearth, Hozier’s third album, released on 18th August, 2023. The sentiment has remained the same.

What has changed in the midst, however, are the ruminations upon why Hozier’s music has the capacity to hold so many captive.

Andrew Hozier-Byrne, a small musician from County Wicklow, Ireland, became an overnight global sensation with his Take Me To Church, which was released in 2013. In the decade that has followed, we have been witness to three albums and an almost cult-like fan following. A vocal advocate for human rights combined with extremely visible allyship towards the queer community, Hozier has since come to represent a figure held in reverence. Subsequent interviews caused the discovery of the significant impact of literature on Hozier’s music, sending the literary community into a tizzy, trying to unearth the hidden layers. Spurred on were also the trained music community that went into the frenzied discussions of pitches, vocal range, instrumentals and the like.

But the unearthing, so to speak, comes much later. For most of the fanbase, untrained academically in either literature or music, it may never come at all. What then forms the enduring enchantment that is Hozier’s music?

While the answer will always remain subjective, for this writer, it has been the authentic voice of primal emotions coupled with the absolute breathtaking magnificence of the ordinary words used to form some of most haunting lyrics that ring on in the ears forever. While Hozier’s style has varied over the years – from Indie rock to Pop music – what has remained a consistent, and thereby turned trademark, is Hozier’s lyrics.

Each song tells a story – underlined sometimes in the suffocating yearning for someone; at other times the maniacal underside to loving and the abuses of being loved; the chilling surrender to an apocalyptic world, the humane nature of eroticism, the screeching voice of protest and a lunatic glee in the phenomenon of death. It is the rendering of the mundane into almost-poetry, set to music.

Hozier takes from life – his own, yes; but also from the meanderings of everyday human existence – and turns it immortal. And amidst the mind-boggling backing of an assortment of instrumentals, his voice becomes that of the literary Bard, authentic and speaking an universal tongue; felt, if not understood, by everyone. His music is a conflation of the mortal and immortal; something tangible, yet ethereal. It is also often wicked, engaging his audience in a playful deceit of words, but never hoodwinking, always upholding the truth.

Written during the pandemic, the 16 songs that make up Unreal Unearth channels the fears and anxieties of the same. Thematically, it is structured according to Dante’s Inferno, the nine circles of hell, but no particular literary knowledge is required to decode the narratives. The entire album is a personal story of an aching love’s journey through the punishments of hell, one undertaken from the bowels of intense distress to the exhilaration of hope.

De Selby (Part 1 and 2) functions as two halves of a beating heart, the organic transition making it almost impossible to differentiate between the two separate parts. The soft vocals take on a lustful tone as the album progresses to First Time and Francesca, with the change in instrumentals mirroring human reactions to eroticism.

Irishness forms an integral part of Hozier’s music, and Unreal Unearth sees probably the most vibrant display till date, with phrases in Gaelic sprinkled here and there, a portion of De Selby (Part 1) sung in the same to Butchered Tongue that expresses gratitude for the survival of Gaelic language and culture. Also featured are folk ballads of the likes of I, Carrion (Icarian) and To Someone From a Warm Climate (Uiscefhuaraithe). The satirical lead single Eat Your Young is a funky- pop, one of Hozier’s emblematic wilful deceipts, hiding in plain sight some of the gravest undertones of the gluttony of war.

Son of Nyx is an orchestral masterpiece. Dark as the album may be – it speaks of the trials of treacherous love in Unknown/ Nth, it is also the tale of undefeated human love on the album, closing with the promise of hope through First Light. Other songs include Damage Gets Done, Who We Are, All Things End, Anything But and Abstract (Psychopomp).

It is almost as if with the “dawn” of the concluding song, hope is reborn into hopelessness of the post pandemic world. The lyrics will remain engraved in those who listen, be it “Heaven is not fit to house a love like you and I” (Francesca), “You know the distance never made a difference to me/ I swam a lake of fire, I’d have walked across the floor of any sea/ Ignored the vastness between all that can be seen” (Unknown/Nth).

While in the months to come Unreal Unearth will be studied and broken down, academically and musically, in thematic and technical terms, what will live on and continue to resonate are the haunting refrains of an intricate human journey through the myriad of feelings and actions, a journey that defines what it means to be human.