In 2004, Shelly and Donald Rubin opened the remarkable Rubin Museum in downtown Manhattan to share their collection of Indian art, mostly objects from across the Himalaya region which they’d been assembling for 30 years. From the start, it was different. The museum encouraged visitor participation at all levels and quickly became a richly rewarding hub for inquisitive New Yorkers to meet. Tim McHenry’s programming of speakers and films was outstandingly imaginative. ‘K2 Friday Nights’ became an institution, and The Mandala Lab invited all ages to use their breathing, sight, hearing and even smell to find greater wellbeing.

Now, on its 20th anniversary, the Rubin is taking another leap forward. Jorrit Britschgi, its executive director, calls it ‘boldly letting go of an old model and redefining what it means to be a museum in the 21st century’, by which he means closing the physical building and transforming the collection and its ideas into a ‘museum without walls’. This is not, as some people expected, simply putting the museum objects online. It is far more ambitious, diverse and specific.

The overall aim is to spread a greater awareness of the Himalaya region’s culture and art, which remains little-known even by many people who study other aspects of Asia. And to do so across the world, for free, in a variety of ways.

One way is through the intellectual Project Himalayan Art, something the museum has started but will develop and expand. It has three complementary parts. One is an exhibition of 50-120 objects travelling to carefully selected college locations which have related fields of study, the aim being to give faculties the tools to incorporate Himalayan studies into the curriculum for one term, enriching a student’s thinking permanently. An exhibition already at the Harn Museum, Florida, will go to Ohio, then Utah. Importantly, anyone can apply!

The second part of this is the Rubin’s digital platform, where images and catalogue entries of the collection will be expanded to include how objects are made, a glossary, maps, etc. Themes such as pilgrimage aim ‘to escape the narrow way of looking at the region’, as Britschgi puts it, and users are encouraged to suggest and even submit new content. The third part is both online and published by the Rubin Museum as a magnificent book boldly titled ‘Himalayan Art in 108 Objects’ – a challenge to anyone who thinks they know that huge and diverse region’s history and treasures.

The overall aim is to spread a greater awareness of the Himalaya region’s culture and art Shutterstock

Making the collection accessible to a wider public is another way the Rubin will reach out its tentacles. Selections of objects will be lent to museums for three to five years. As most museums do not have Himalayan art, let alone a curator for it, the loans will widen and enrich the host collection and will also come with plenty of information and new ideas for how to enjoy them. Additionally, there will be grants for artists who are closely related to the Himalayan region, and for people documenting its arts.

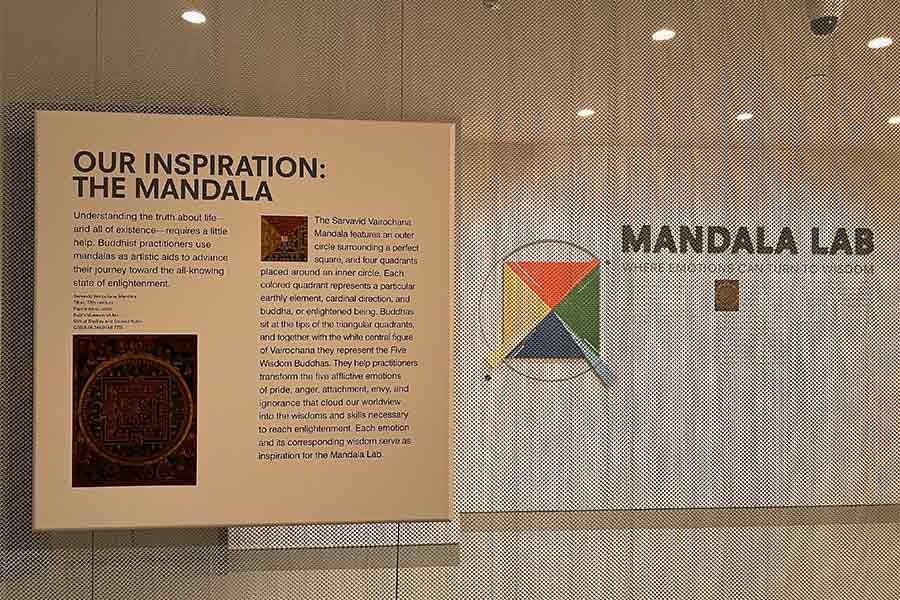

Then, there is the experiential Mandala Lab, a great success at the museum with an edition already on its travels to public spaces around the world. It has already visited London and Milan. Targetting people of all ages, it is usually a first-time encounter with Himalayan ideas such as meditation through controlled breathing, creating a sound and then listening carefully to it, or experiences a smell and learning that each person has a different response to it, different associations. Again, anyone can apply!

The experiential Mandala Lab is a great success at the museum with an edition already on its travels to public spaces around the world Shutterstock

As Britschgi sums up, smiling broadly: ‘We radiate out from what we’ve built up!’

Until the Rubin comes to your college or city, there are expanding digital experiences to enjoy, too, such as mindfulness and meditation podcasts including a special one for early risers. Not only are Project Himalayan Art and Himalayan Art in 108 Objects also on the platform; so too is the Rubin’s Spiral magazine. Meanwhile, a slightly amended version of their blockbuster show, ‘Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now’, will be soon be in Tadeo Ando’s beautiful Wrightwood659 building in Chicago through next winter and spring (November 7 to February 15).

The Rubin’s seminal announcement coincided with Asia Week New York 2024. So, when their big final show opened on the festival’s first day, March 15 (to close on October 6), all six floors were crammed with collectors, dealers, curators, and museum directors from around the world keen to see the museum’s finale, even if they’d missed out on New Yorkers’ beloved Rubin up to now.

What they saw was contemporary meeting ancient, with a strong symbiotic effect. The 30 or so artists mostly came from the Himalaya region and its diaspora. They were invited to respond to the collection and had their works displayed ‘in conversation’ with pieces in the collection, which not only revealed the artists’ thoughts about their personal and collective histories, but also gave new meaning to the historic pieces. For instance, right at the entrance, appropriately, is the museum’s 11C sandstone Ganesh statue from Madhya Pradesh. In front of it stands a caricature Uber Rat by the young ceramicist Shushank Shrestha from Kathmandu, who has just completed his studied in New York state. Upstairs, Chitra Ganesh, a lifelong Brooklyn resident, has made a provocative and timely animation, ‘Silhouette in the Graveyard’. Using contemporary political, social and ecological images, she incorporates a figure of Maitraya, the Future Buddha, whose arrival will usher in a new age when the terrestrial world has lost its way. Visitors can look at the Rubin’s own Maitraya Buddha, a gilt copper alloy figure made in Mongolia at the turn of the 18-19C, while watching Ganesh’s animation being screened on the wall behind.

Since it first opened, the Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room has been one of the most popular installations at the Rubin Museum Rubin Museum of Art

A show-stopper fills the stairwell: a cascade of multicoloured disused prayer flags with horses’ heads emerging from it. It is by VAST Bhutan, a three-artist collective led by 62-year-old Asha Kama Wangdi, who was born in Punakha, Bhutan, lives over the mountain in Thimphu, and earned his arts degree in the UK. The piece for the Rubin is inspired by the lungta, or ‘wind horse, a mythical pre-Buddhist Tibetan creature who has the speed and strength to carry prayers to heaven, and is an auspicious sign of positive energy and life force. To make it, forgotten flags were collected, and boxfuls shipped to the Rubin to be repurposed for the installation. The message: With more and more people seeking more and more merit by placing in nature and in monasteries too many factory-made prayer flags using acrylic paint, the flags which should bring good are now unintended pollutants. Poignantly, its Rubin collection partner is a small, simple woodblock, which would formerly have been used to print thin cotton flags using vegetable dyes.

Stimulated by the Rubin’s exceptional show, Asia Week NY attendees galloped around Manhattan for the next seven days. To museums, making a beeline for The Met’s show of Howard Hodgkin’s Indian paintings, the majority part of a recent acquisition. To commercial galleries, where quality pieces shown by London dealers Brendan Lynch and Oliver Forge Ltd and Francesca Galloway, as well as US dealer Carlton Rochell Asian Art, were being snapped up by international museums. And to thoughtful shows at New York’s Asian culture societies – Japan’s meditative Zen paintings from the Gitter-Yelen collection, Korea’s metal works by John Pai, and Asia Society’s disturbing expose of options for climate change action. Not forgetting a dance through the auction houses’ offerings. All oiled with parties and networking.

Can this 6th Asia Week New York, chaired by Brendan Lynch, be matched next year? And how far will the Rubin Museum without walls be stretching by then?