In order for human bones and joints to move efficiently, there should be normal amounts of opposing force acting on the joint/bones from the muscles surrounding the joint. There is a necessity for good balance between the strength and the flexibility of these muscles so that they can work in sync to keep joint functions efficient and powerful.

Muscles rarely work in isolation; they function as integrated groups. Two muscles may provide opposing forces from either side of the joint in order to achieve joint movement. For instance, when the abdominal muscles pull upward on the pelvis and the hamstrings on the leg pull downward, it helps the pelvis to rotate posteriorly and flatten the lower back. This is referred to as a force-couple relationship. On the other hand, when the back extensors pull upward on the pelvis and the hip flexors pull downward, these muscles work a force-couple to rotate the pelvis anteriorly and extend the lumbar spine.

In fact, the opposing forces of the hamstrings and the abdominal muscles or lower back muscles are involved in all kinds of movements, like bending from the waist, squatting, or twisting.

When there is muscle imbalance, it compromises the joint movement related to those muscles. For example, the quadriceps and the hamstrings exert opposing tensions on the knee joint. A tight hamstring will restrict the knees from extending fully, or moving normally, putting extra stress on the quads and the kneecap.

This may sound like it’s only important for athletes, but it’s not. The average person is actually much more susceptible to injuries and chronic pain because of muscle imbalances. Athletes get their muscle imbalances checked and rectified by professionals, while most of us have to live with these imbalances without even knowing about them.

Muscles can shorten in as little as two to four weeks if held in passively shortened positions without any stretching or use through a full or functional range of motion. For example, continuously sitting for long hours without any hip extension (desk workers, cyclists, long-haul drivers) can shorten the hip flexors. Chronically shortened hip flexors will create an unnatural forward pull on the pelvis, which in turn will put stress on the lumbar spine and cause lower back damage and pain.

From a functional point of view, muscle imbalance plays havoc with musculoskeletal neural activity. Neural activity refers to the brain’s messaging network with the muscles. When a muscle gets shortened, it is described as becoming over-active or hypertonic. It tends to steal or “hijack” neural messages from the brain and tends to fire by suppressing another muscle which is weak and long and has impaired neural response or sensitivity. This is a condition called synergistic dominance, in which the synergists carry out the primary function of a weakened or lengthened prime mover. It needs no elaboration on why that might lead to injuries or chronic pain.

What is muscle imbalance?

The joints in your body are enveloped by muscles that coordinate their movements. These muscle groups counterbalance each other and work together to complete a movement. The joints are well supported, aligned and functional if these muscles around the joint maintain their relationship (measured in terms of tonicity) with each other. However, if the muscles on any one side become weaker or stronger it alters the relationship that these mutually have with each other. This causes a muscle imbalance. Muscle imbalances need to be attended to right away, or they can cause serious injuries.

Occupational and lifestyle positions (for example, working at a computer, long hours of driving a vehicle, repetitive movements like long, slow jogging, wearing high heels) and poor movement techniques often create postural challenges that over a period of time alter the human movement system. The human movement system is a very complex, well-orchestrated system of interrelated and integrated myofascial, neuromuscular and articular components. A smooth and optimal, almost seamless integration of all these systems contributes to the well-being of each individual by putting less stress on muscles, bones and joints. This is often referred to as “correct posture”. If you have heard your teachers, coaches or parents say: “Stand tall, stop slouching, pull your shoulders back…,” you will understand what I am referring to.

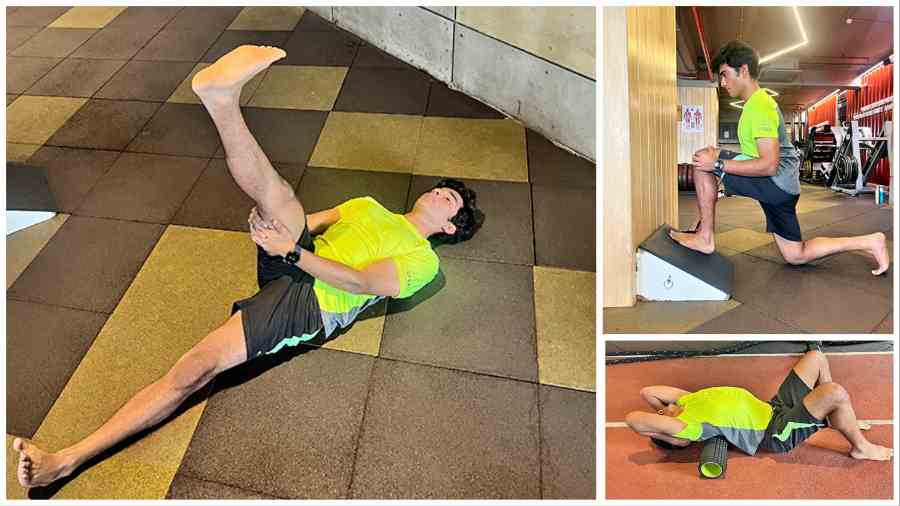

Stretch all the tonic muscles: (Clockwise from left) Hamstrings, calf, shoulder internal rotators and chest

Poor posture, on the other hand, is the faulty alignment of various body parts, producing increased stress and strain on supporting structures, ultimately compromising balance and movement efficiency and leading to degenerative changes and pain. It is often perpetuated by muscle imbalance.

Muscle imbalance and postural deviations can be attributed to several factors, including the following:

- Repetitive movements (pattern overload)

- Side dominance

- Poor joint integrity and stabilisation

- Poor neuromuscular efficiency

- Poor or imbalanced muscle training

- Congenital conditions(for example, scoliosis, polio)

- Pathologies (for example, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis)

- Structural deviations (for example, tibial or femoral torsion, femoral anteversion)

- Trauma (for example, surgery, injury, amputations)

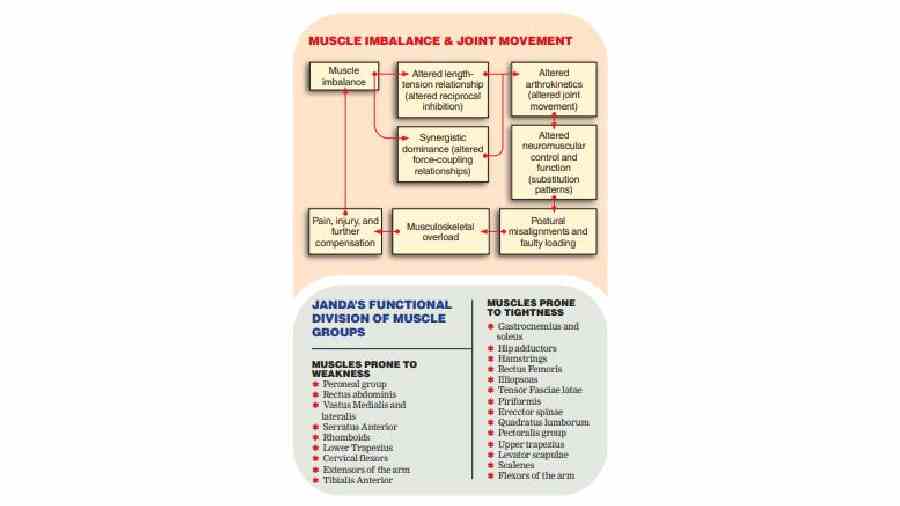

Muscle imbalance alters movement at the joint and beyond the joint of origin (for example, an anterior pelvic tilt is not restricted to merely the pelvis but may change the static position, and movement of, the cervical vertebra). As joints bear load and move in a deviant manner, the body strives to discover paths of lesser resistance (Law of Facilitation) potentially overloading the musculoskeletal system. This inevitably increases the likelihood of discomfort, injury and pain. This sequence is illustrated in the chart.

Exercise considerations

A restorative exercise programme must endeavour to reverse the ill-effects of faulty patterns. To do that, muscles need to be identified and isolated as per their nature of tonicity. Vladimir Janda divided muscles into functional groups prone to weakness and prone to tightness. A well-designed exercise programme will attempt to increase passive and active range of motion in groups prone to tightness and aim to strengthen or condition muscle groups prone to weakness. For example, the gluteus group of muscles is traditionally a weak muscle and needs to be conditioned. Exercise specialists should prescribe exercises that increase the tone in this muscle. Developing strong and functional gluteal muscles will reduce the synergistic dominance in the lumbar erectors (lower back muscles) and help to eliminate a potential cause of back pain.

The calf muscles, on the other hand, are prone to tightness and hypertonicity. They need to be lengthened with consistent stretching protocols to restore them to their original length. Doing that will lead to better kinematics in the ankle joint, superior loading in the lower extremities and perhaps lower incidences of knee pain.

Ranadeep Moitra is a strength and conditioning specialist and corrective exercise coach