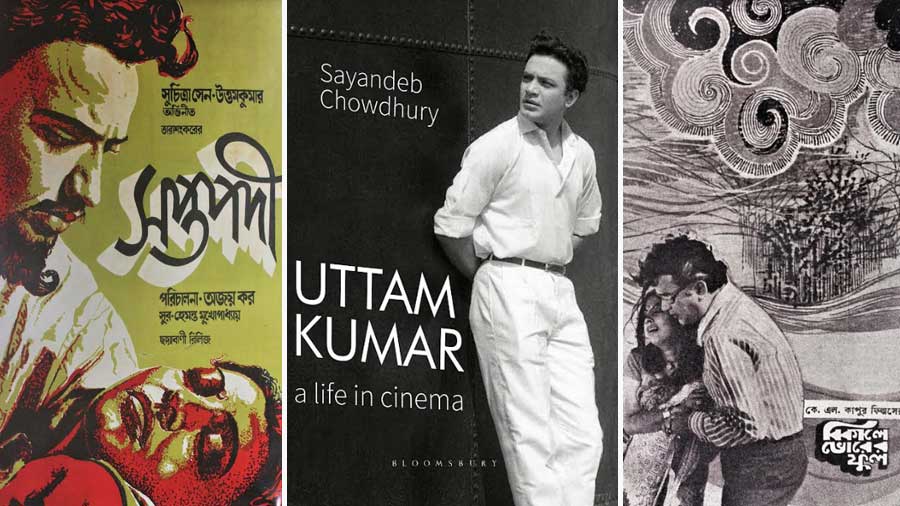

The following is an excerpt from Uttam Kumar: A Life in Cinema by Sayandeb Chowdhury.

Little did Uttam know that his stardom had stretched well beyond the limits of the city. This was in the early 1960s. It was an outdoor shoot at Jiaganj, an ancient riverine town about ten kilometres from Bengal’s medieval capital of Murshidabad. As a red herring, it was announced well in advance that Uttam Kumar was indisposed and was not travelling with the crew. Clandestinely, the crew with Uttam arrived by train at the town late in the evening. And defeating all attempts at concealing his arrival, the small, scenic station was already overrun with people. The crew, nervous and caught off guard, sat inside the locked compartment for a long time waiting for help. After much confusion, Uttam was rescued by local men who carried him prostrate (changdola in colloquial Bangla) out of the train and into a car.

A key river scene was scheduled to be shot the morning after. The crew, heckled, harangued, exhausted, retired for the day thinking that the ordeal was over. But it was just the beginning.

A still from Nisithe (1963), the movie which Uttam Kumar was shooting for at Jiaganj

Next morning, as the team reached the banks of the river they were dumbstruck. On both sides of Bhagirathi, that side being Azimgunj, hundreds were travelling on foot—men, women, old people and children—walking in a line towards the bank with the look of what seemed like a mission. Before the team could fathom what was happening, a local messenger arrived with the news. People had set out at daybreak from the Muslim-majority villages miles away, so that they could have a look at Uttam Kumar. It was not the usual crowd that would gather at shooting sites. There was only a handful of crew members and they were inept to ‘attend’ to the gathering hordes in any way. Instead, the crew hurried with the boats to the middle of the stout river and proceeded with the shooting. But that had a telling effect. As per Uttam’s own version of the story, mounds of sodden earth soon started flying from both sides of the river. The crowd wanted to get close to their idol; nothing less than that would do, and hence the lovelorn vehemence. One big piece was also aimed for the star himself, because he showed no inclination to gratify the demand. That piece, recounted Uttam, landed on the poor director, who was trying to dodge another piece from another end. There was total chaos. But the crew managed to escape to their den largely unhurt.

One can read this episode as a simple case of mob excess that is not unheard of in the annals of cinema. The other reading should consider this episode, which was not unique in case of Uttam, as symbolising a bigger query, which is about Uttam’s reach as a star. This was in the 1960s; there was no way that the ‘idea’ of a cinestar would travel through television or other means of media to distant lands. The only ‘carriers’ of cinema ephemera, if at all, were city periodicals, while broadsheets, which reached the provinces, rarely carried news from the world of ‘entertainment’. Film theatres were few and far between. Cinema was not yet the vehicle of mass outreach in the provinces.

So, what was the basis of a stardom of such scale taking shape amidst a people whose physical familiarity with Bengali cinema was, at best, partial? At a more cultural level too, there could not be any feasible explanation. After all, Uttam Kumar did not ‘build’ his fandom through the more realisable channels of loud mythological or period films. If at all, his cinema was unapologetically middle-class. There were exceptions but they were not enough to create any recognisable template for the provincial viewer. In short, his cinema was deliberately dissociated from the traditional tropes, Hindu or Muslim, that apparently appease the people in the hinterlands. So, there was no palpable reason why Uttam Kumar’s body of work would cross the divided territories and attract obsessive mass adulation in a far-flung Bengal village.

Either we have historically misread the gap between ‘the country and the city’, or Uttam Kumar was that rare thing—a star who could transcend the divisive logic of cultural pattern and taste. Moreover, as Uttam’s stardom expanded its geography, it also ‘carried’ Bengali cinema’s reach outside the urban towns and centres in the 1950s. In that case, the fundamental novelty of cinema, its potential as a storytelling medium, and the identifiable and aspirational cultural sphere that Uttam’s cinema exemplified merged into the figure of the star-actor. That could explain some of it, if not all of it.

In fact, this link that Uttam’s stardom managed to establish was both unprecedented and unsurpassed. Before or after him, no actor has created even a surfeit of that transcendental link between the stiff upper-lipped cinema consumer of Chowringhee and the vast multitudes in the bosom of Bengal. Historically, there was only one man in Bengal who could get thousands spontaneously to march to a river one early morning and shower him with love in the form of mounds of sodden, fresh muck.

Photographs of ‘Saptapadi’ and ‘Bikele Bhorer Phool’ are inserts from ‘Uttam Kumar: A Life in Cinema’ published by Bloomsbury Academic India

Author, Sayandeb Chowdhury on his preoccupation with Uttam Kumar’s work and why he chose this excerpt:

I saw Uttam, much like my generation, on television broadcasts of Bengali cinema throughout the 1980s. Something about him impressed me a lot but I could not put my fingers on what it was. Later, as cinema and I caught hold of each other, I became increasingly fascinated by Uttam. The more I saw cinema elsewhere and detested what I saw in Bengal, the more I detected a kind of globalism in Uttam’s decades-old performances. I started to think fully about his cinema and gradually decided that I should not let this fascination go to waste. My thoughts started to take the form of a book, but what the difficulty lay in trying to give shape to such a wide-ranging and phenomenal stardom, as there were no precursors to follow. I do hope readers will be able to appreciate the way I have gone about the book.

I have chosen this excerpt because it is a fascinating story, narrated partly by Uttam himself. It gives the reader an opportunity to bask in his charm and to think about the scale and nature of the unique stardom he embodied.

Sayandeb Chowdhury teaches in the School of Letters at Ambedkar University Delhi. His research and teaching interests are in colonial and postcolonial visual modernisms, cinema and photography studies, adaptation studies and city studies. He was a UKNA Fellow at the International Institute of Asian Studies, Leiden, in 2015, and a Charles Wallace UK Fellow in 2016. He has written on art, books, politics and cinema for various publications.