Shortly after he gets struck by lightning, Jaison aka Minnal Murali asks his nephew about American superheroes. But spandex-clad heroes play no part in Jaison’s journey — his human father does. Jaison learns his father was a theatre artiste who died saving people from an explosion during a performance of his play Minnal Murali.

There’s a lot to be said about legacies. They shape who we are and what we see in the world. The Malayalam superhero film takes a long time to establish its hero’s personal history and focuses on his human foundation. The Basil Joseph film knows that there are some problems superheroes can’t identify, but communities can.

Hollywood’s superheroes are canon, they have their own comic book legacies. But their stories are in desperate need of an update. Faustian, evil scientists or alien overlords don’t endure as motifs of threats in this world. Our scientists are overworked and underpaid and simply do not have time to make giant, mechanical tentacles. In Minnal Murali, the worst bully is the village cop, who won’t approve Jaison’s passport. It’s the oppression that hits home. The film pares down the miseries of being human which helps elevate its message.

The starting point

Minnal Murali’s town bumpkin-turned-messiah is flawed, lost and self-serving. He has bad breakups and a wife-beating brother-in-law. He wants to escape his village, like so many young men in Kurukkanmoola. It’s entirely possible that some American superheroes too have abusive relatives — we just don’t know about them. In fact, we hardly know anything about where the heroes come from.

There’s a reason why origin stories need to be told. They talk about fathers and mothers and school bullies. They are meant to humanise supermen. Arc reactors, Russian assassins and Ra’s al Ghul’s combat training may define the superhero oeuvre, but it’s entirely and obviously fiction. It was in a comic book and now it’s on the screen. Despite its Scorsese-baffling success, Hollywood’s superhero origin movies fail to give its viewers a moment alone with their heroes and their human regrets.

What came before the mask and cape

In the MCU or DCEU parlance, heroes are misfits, even the incredibly rich ones. But there’s so much more to a hero’s creation story than social isolation. They are essentially meant to show us what came before the cape and the mask.

Minnal Murali’s Jaison is a bad employer, he’s petty, vindictive and does precious little with his superpower in the first two hours. The moment he gets his hand on a mask, he uses it to assault his ex-girlfriend’s father. The film wastes no time in setting him up as a good example. Hollywood’s superheroes are designed to be gods (some of them actually are gods). Kevin Feige’s MCU expands like modern mythology, it just happens to be a first-world one. But it doesn’t do a good job at representing Americans either.

Bruce Banner was born in Ohio, a swing state that went red in the 2021 elections. Scott Lang, who becomes Ant-Man, is from Florida, a prized battleground in American politics, where Trump scored a whopping 29 electoral votes this year. Marvel’s superheroes have always been political, there’s no denying that. But origin stories can be powerful vehicles for addressing the American divide.

“Minnal Murali has to move out of Kurukkanmoola definitely,” Joseph says about his superhero. But Hollywood’s origin stories begin only once the hero is out of Middle America, and that’s a problem.

Home is where the hero is

When it comes to first-chapter stories, some things are key. First is the idea of ‘home’. Minnal Murali realises he wants to be the hero his village needs, a sentiment also echoed by Batman. DC’s Gotham is said to have been modelled to resemble an exaggerated, unhinged version of New York City. NYC is also home to the Avengers, Jessica Jones and The Punisher. Even Xavier’s School for Gifted Youngsters is located in New York.

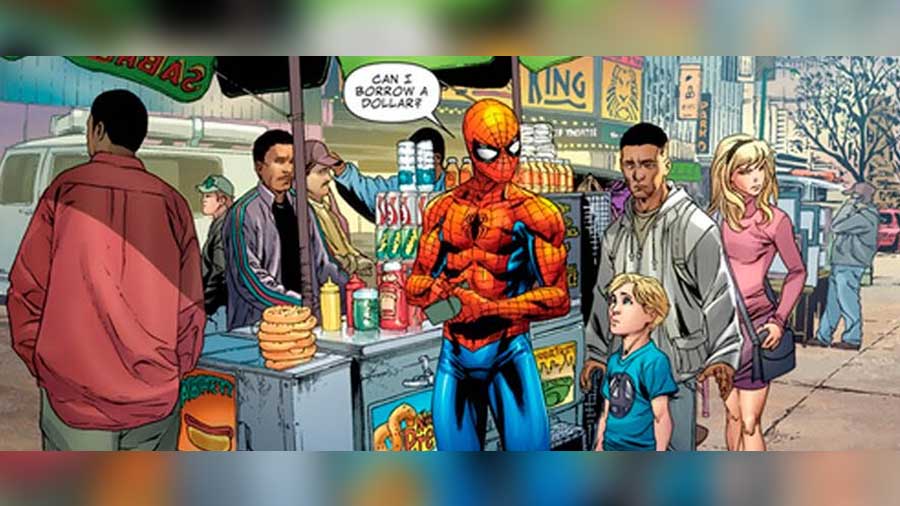

New York is a crucial motif in Stan Lee’s comics Marvel

Stan Lee’s rich pastiche of New York City has a character of its own; it’s the city that talks back and it’s an illustrator’s dream setting. But Minnal Murali works because it gives a voice to its fringes. It doesn’t unsee the existing regressions and the problems even if it can’t solve them instantly. Talking about human limits is crucial to any story that talks about power, and this makes Minnal Murali so resilient as an origin tale.

Jaison’s transition to a costumed hero isn’t spurred by an alien invasion, nor does he dream of being recruited by a superhero task force. His biggest priority is getting his hands on a passport. The film carries an angry message about class struggle, about hyper-local social set-ups that enable privilege and oppression.

In an origin tale like DCEU’s Joker, the hero can shoot people. Of course, there’s a larger conversation about mental health involved. But the point is, the everyman is hapless and possibly doesn’t own a gun. Even if Jaison does get a passport, his life as an immigrant could be rough, give or take his reflexes. Minnal Murali isn’t afraid of going there, of addressing how money and class hold you back.

The Malayalam new-wave cinema vies for universal story-telling with locally-rooted observations. Kumbalangi Nights, Angamaly Diaries, Ente Ummante Peru move away from metropolitan stories to uphold the many existing cultures within the state. There are challenges to localising a superhero but the point of origin stories is to trace what came before the powers did. How would Tony Stark vote if he wasn’t Iron Man? Does Doctor Strange have student loans? Who can tell?