Two women, one exalted in the nationalist consciousness and the other relegated to obscurity, were in the limelight at The Bengal Club on February 22 where historian and Ashoka University chancellor Rudrangshu Mukherjee’s book, A Begum & A Rani: Hazrat Mahal and Lakshmibai in 1857, was formally launched.

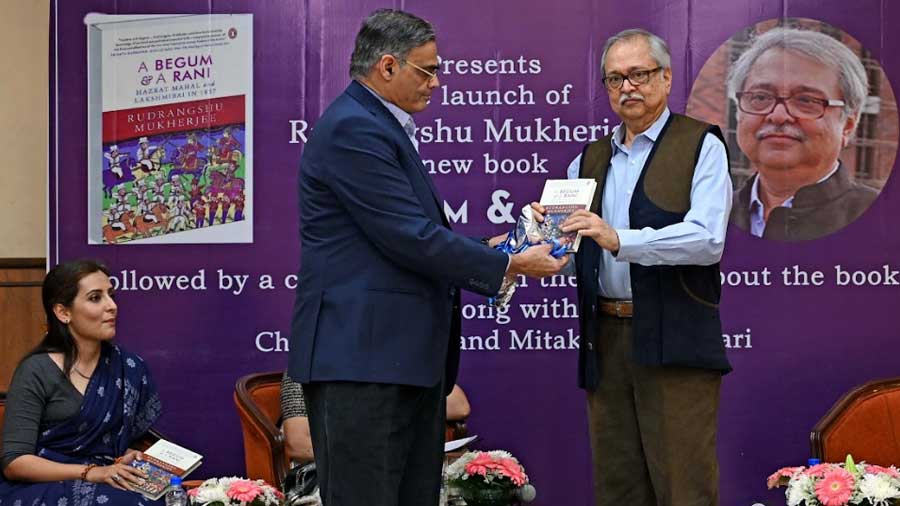

“Even though the book was published in August 2021, it has never had an official release so this is the first, and only, formal release. And I am happy that it is taking place in The Bengal Club, which is like a second home for me,” said Mukherjee after A Begum & A Rani was launched by Dr Sandip Chatterjee, the chairman of the club’s library sub-committee.

“The two ladies in the book are characters who are in much contrast to each other. One has been resurrected by Rudrangshu from oblivion and obscurity and the other has been recast in her glorification and glamour,” said Chatterjee, kicking off the evening’s programme.

In conversation with Mukherjee were two members of the library committee — Chaitali Maitra, a teacher of English, and Mitakshara Kumari, advisor to the government of Chhattisgarh. Between their informed questions and Mukherjee’s ability to bring to life characters and situations from the pages of history, it made for an enthralling discussion.

(L-R) Mitakshara Kumari and Chaitali Maitra in conversation with Rudrangshu Mukherjee

Maitra began by talking about the series of truths laid out in the book’s introduction — the unhappy and poverty-stricken 19th century India, the importance of individuals in history writing, the singularly important insight of remembering history, which also has the flip side of forgetting history, and the various aspects of rebellion and resistance.

Her first question to Mukherjee, whose core research area has been 19th century India, was about the land revenue system of the British, which set up the context for the two women’s roles in the Indian rebellion of 1857.

Mukherjee wove a picture of what he called “the British conquests of India”, from Bengal to Punjab, over a period of 80 to 90 years and how the British, who were in India to “make money”, implemented different land revenue systems in different parts of India.

“The most well-known of it was the one in Bengal, which is the Permanent Settlement of Bengal. One historian magnificently described it as the Magna Carta of British rule in India. That was the first. The others were sometimes radically different from the Permanent Settlement system. There was the Ryotwari system in the Madras and Bombay presidency and the Mahalwari system in North India and parts of Central India,” said Mukherjee, focusing on the Mahalwari Settlement, which the two areas that are under discussion in the book — Jhansi and Awadh — were a part of.

Rani Lakshmibai, a reluctant rebel who actually exercised choice

Kumari brought one of the heroines — Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi — into focus by noting how the story of 1857, as told by Mukherjee, throws up a Rani Lakshmibai who is much more complex and layered than what we learned through our history books and through popular narrative. She wondered how despite being a “reluctant rebel” she came to be in such an exalted position.

Mukherjee’s response threw up a woman who was committed to the welfare of Jhansi and her subjects. Her reluctance to join the rebellion in the first flash, in June 1857, was because she couldn’t decide at that time whether her subjects and her own interests would be best served if she turned a rebel, explained Mukherjee.

There were two other factors that might have dissuaded her from joining the rebellion, said Mukherjee. One was that the sipahis of Jhansi who rebelled on June 6-7, and some of the common people of Jhansi who joined that rebellion, broke the promise of sparing the lives of British officials if they surrendered. They killed every single white person who came out, irrespective of age and gender. “So Jhansi had the stain of blood on it and as the queen of Jhansi she was conscious of this stain and she was also conscious about the fact that she would be held responsible for the massacre that had taken place. She would be held even more responsible if she joined the rebellion,” said Mukherjee.

The other factor was that once the mutineers had killed all the British, they felt that their job was done in Jhansi and they sped away to join the rebellion in Delhi. So from that time, Jhansi was free of rebels and of the British. Lakshmibai spent that time from June to the winter of that year trying to reestablish the administration of Jhansi under her dispensation.

“I think in more ways than one, Lakshmibai has been done a disservice by historians. She evolved as she met circumstances and the reality of that summer and of that winter. It was not a matter of black or white. She went through a process where she actually exercised choice. A woman in the 1850s is actually making choices and making very difficult and complicated decisions,” said Mukherjee, describing her initial overtures to the British and then her eventual decision to stand with the people of Jhansi who had turned rebellious.

In his narration of the events Mukherjee painted a picture rife with suspicion, tension and death, and it was almost like watching a movie on the events that unfolded, from her daring escape from the fort on horseback to her ironic death at the hands of a sniper when her horse stalled at a ditch.

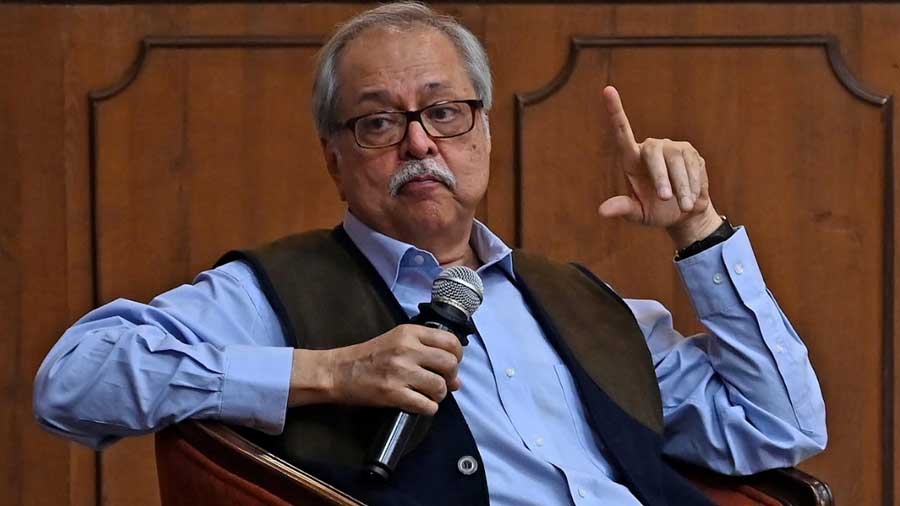

Author Rudrangshu Mukherjee makes a point during the conversation about his book, at The Bengal Club

Hazrat Mahal, from slave girl to begum to regent

The discussion then moved to the other heroine of the book, Hazrat Mahal, and how she was thrust into a leadership role without which “she wouldn’t even have been a footnote in history”. She was the daughter of an Ethiopian slave of Wajid Ali Shah, who trained as a dancer and a courtesan in the famous dancing school in Lucknow called Pari Mahal. “That is where she caught the eye and fancy of Wajid Ali Shah. And Shah made her one of his ‘mutah’ wives,” said Mukherjee, pointing out the scene from Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj Ke Khiladi where general Outram asks his assistant, Weston, what a mutah wife is and Weston explains that “mutah” wives are wives of pleasure and they are temporary.

She became pregnant by Wajid Ali Shah and gave birth to a son, after which Shah made her a begum and gave her the title of Begum Hazrat Mahal. But Shah’s mother, a very domineering personality and very influential on him, didn’t like the idea of a slave girl being a begum and made Wajid Ali Shah give talaq to Hazrat Mahal.

“So here was a woman who lost her privilege and access to royalty. We don’t know what happened to her between 1850 and 1856. All we know is that in 1856 Awadh was annexed by a fiat of Lord Dalhousie. The British troops march into Awadh and in a few days it is decided that Shah would be exiled to Calcutta, where he builds his own mini-Lucknow,” said Mukherjee, who once again added colour to the narrative with insights into Shah’s departure from Lucknow and how on the eve of May 30, 1857, the sipahis in Lucknow rose in rebellion, defeated the British and put Shah’s son, Birjis Qadr, on the throne as the Wali of Awadh. Since Qadr was around 11 or 12, mother, Hazrat Mahal, was made a kind of regent, who would run affairs on behalf of her young son.

“This is how Begum Hazrat Mahal enters the pages of history. Once she takes over the reins she establishes an administration, directs how the British are to be fought and how they are to be removed from Awadh. So she is a typical general who is not out there in the front of the battleline, but is actually working in the backroom, making all the plans and strategies,” said Mukherjee.

She also issued, in her own name and her son’s name, ishtihaars or proclamations to rouse the morale of the army and the rebels, to point out the innumerable misdeeds, according to her, that the British had committed in India, and when in November Queen Victoria issued a proclamation announcing that the East India Company would no longer be ruling India, she would, a counter proclamation known as the Begum’s Proclamation. “It is a paragraph by paragraph rebuttal of every single point that the Queen’s Proclamation made. So she was setting up administration, drawing up plans and strategies for battle and she was issuing what would be called propaganda and persuasion,” added Mukherjee.

Rudrangshu Mukherjee signs a copy of his book after the programme, at The Bengal Club

Kumari pointed out that Mukherjee notes that 1857 was a war of arms but it was also a war of words and aptly said that it “sounds like a very modern political campaign” with the ishtihaars, the fake news, rumours and smear campaigns, and the Badshah’s proclamation which was like a political manifesto of a political party.

“You are absolutely right. It was also modern in another way, all these ishtihaars and pamphlets were printed. They took advantage of modern technology that was available to them. It is often said, even by very well established and even famous historians, that this rebellion was backward looking. But the rebels were completely aware of modern technology,” said Mukherjee.

History as an act of retrieval and selective retrieval – history is also a war of words

“These two women were extraordinary figures because they strode upon a male world, a world in which every single decision was actually taken by men. In such a world they established their dominance, they established their leadership. The trajectories are somewhat different,” said Mukherjee.

Lakshmibai in some ways had been trained to some practices that were considered to be male. Hazrat Mahal was a dancer and a courtesan, who had no access to the arts of warfare. But both used what they had to their strength.

Dr Sandip Chatterjee delivers the vote of thanks

Why then does history remember them so differently? One died in battle, one in obscurity. “Hazrat Mahal didn’t die a soldier’s death. She fled to Nepal and died in obscurity. That makes all the difference,” said Mukherjee.

Is history then the villain of Mukherjee’s new book? “History is an act of retrieval and selective retrieval – history is also a war of words. We have to be engaged constantly in debate. I might disagree with some of the reconstruction that is being made of India’s past but they have a right to reconstruct it the way they want it. If the nationalist movement could reconstruct the past in a particular way then why not now? We debate about it and through these debates the nuances come out,” said Mukherjee.