There is no universally accepted way of identifying a Parsi. In the early 19th century, Parsis were defined by their distinctive clothing, which is not applicable today. On the other hand, Zoroastrians coming from Iran and settling in India were simply identified by their Sudreh and Kusti and their knowledge of prayer lines.

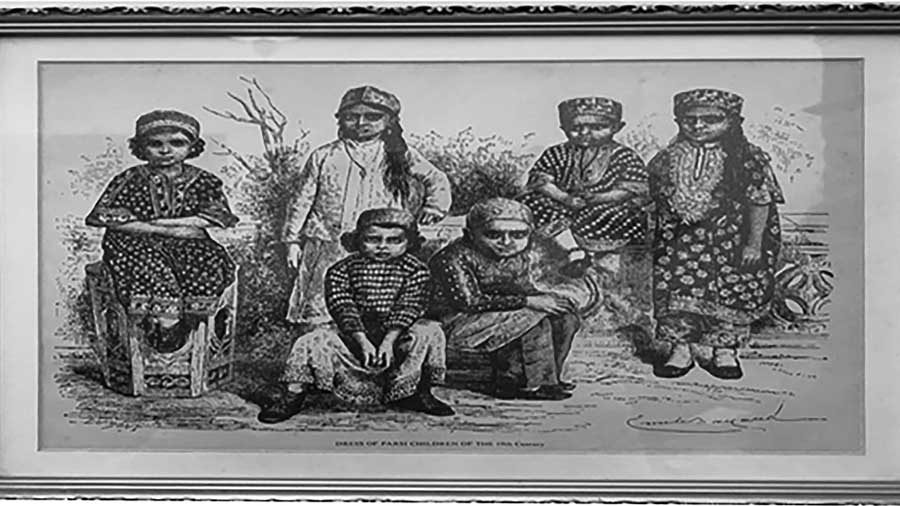

Dosabhai Framji Karaka in his book – The Parsis: Their History, Manners and Customs, 1858, writes about the unique yet simple attire of a Parsi: The dress worn by a Parsi child consists of a single piece of garment called the jhubla, which extends from neck to ankles. The ‘topee’ or skull cap covers the head and completes the dress.

Children wearing jhublas in the 19th century All images from the book

When a child is formally inducted into the religion with the sudreh and kusti of the Zoroastrian religion, the ‘jhubla’ is thrown off. The sudreh is made of linen or net, while the kusti is a thin woolen cord or cincture of 72 threads. These are generally worn at home. In Avestan language, the former is called ‘Sutteher Pesunghem’, which means ‘the garment of the good and beneficial way’. The kusti is passed around the waist three times and tied with four knots.

At the first knot, the person says, ‘There is one God, and no other is compared to him.‘ At the second knot, he utters, ‘the religion given by Zarthost is true’; at the third, she says, ‘Zarthost is the true prophet and he derived his mission from God’, and at the fourth, ‘perform good actions and abstain from evil ones’.

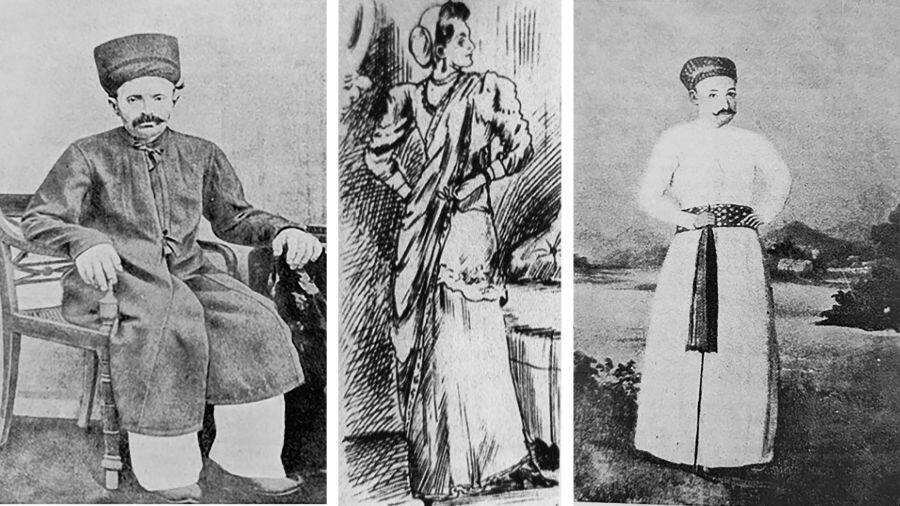

A waist coat, loose cotton trousers, slippers, and a skull cap are also commonly worn by Parsi men. When going out, he puts on an angrakha or loose ungirdled tunic, the sleeves of which are twice the length of the arms and are folded up in wrinkles.

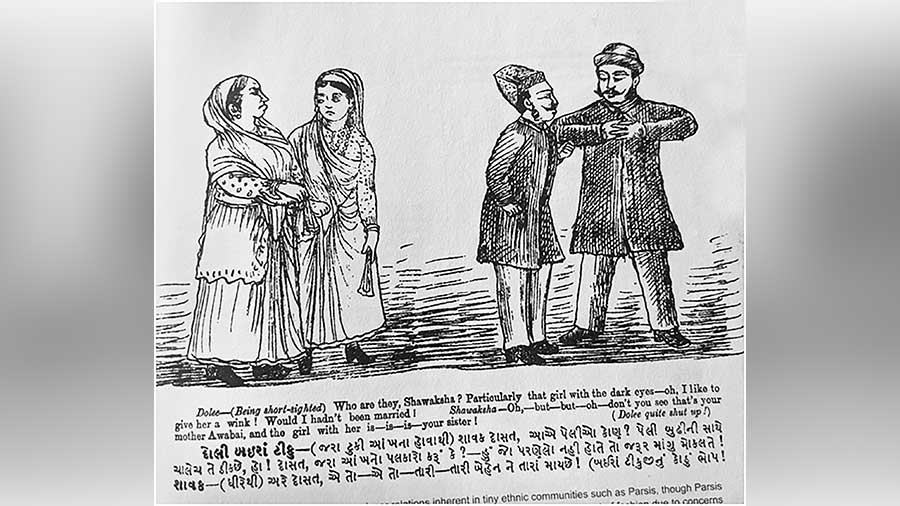

An illustration from 'Parsi Punch' — the ladies are dressed in saris with a long sudreh showing, and their heads are covered, the men are wearing long coats and white pants with black headgear

Over the skull he wears a dark chocolate turban. The full dress of a Parsi man, in addition to this, consists of a ‘jama’ of white linen and a ‘pichoree’. The sleeves and upper portion of the former are like the angrakha, but the skirt is full and resembles an English woman’s gown. The ‘pichoree’ is a long cloth, about a yard wide, and many yards in length and is passed around the waist in successive folds.

Parsi women are generally graceful and well formed. They are robbed of a part of their beauty by the custom of concealing their hair under a ‘mathabana’, a thin muslin cloth worn covering the head. They also wear the sudreh and kusti, and wear silk trousers with a silk vest with short sleeves called the kanchari or ‘choli’. Over this is worn a sari, which is several yards in length and embroidered. The rich wear jewels, necklaces, nose rings, bangles at the wrist and ankles and sometimes even the slippers are adorned with pearls.

L-R: The long coat and white pant worn outside the house in 1800s; A Parsi woman in traditional sari and mathabana and long sudreh; The formal traditional dress 'Darukhanawala, Parsi Lustre on Indian Soil' and 'Hindi Punch'

The dress of the modern Parsi differs from that of their ancestors in Persia and by their present coreligionists in that country. They have adapted the present costume in accordance with the agreement with the Hindu princes, who received them in India. That is why the angrakha and turban of the men, and the sari of the women resemble Hindus.

In the celebrated Saklat vs Bella lawsuit of 1914–1925, Shapurji Cowasji described Bella’s mother as a Parsi – ‘She was a Parsi lady: I formed this opinion from her talk and her dress when I saw her. She wore the usual Parsi dress. She had the usual Parsi features, not very dark, not very fair… When I went to see her, she put the ‘kore’ (i.e., the border) on her head. She wore a Mathabana. I saw the Sudreh projecting from her sari.’

The sharp nose, the unmistakable physical feature of the Parsis, was joked about in the Rangoon courtroom in the Saklat vs Bella suit. When asked to describe typical Parsi features, the lawyer, Mr Connell, pointed to Mr Hormusji and Mr Patel, two of the Parsis in the room. To everyone’s delight, the magistrate replied that he would not allow them to be put as exhibits.

Jenny Rose in her book Zoroastrianism: A Guide for the Perplexed, writes:

“Iranian Zoroastrian immigrants who seek asylum in India under the aegis of the BPP must produce an identity card issued by a local Anjuman (Zoroastrian Council) within Iran; they must possess a sudreh and kusti, and be able to recite in Avestan the two cardinal prayers of the ‘ahuna vairya’ and ‘ashem vahu’. It is through demonstrating such practical knowledge of daily aspects of the faith that the applicants are recognised as having been initiated into and professing the religion. They have become eligible to receive the support of the Parsi community.”

Navjote ceremony of Mehta's three grandchildren

No questions are asked regarding Ancestry. No DNA Tests are done. As Justice Beaman remarked, ‘they are ready to admit any and every Irani Zoroastrian, about whose antecedent they cannot possibly know anything.’

Iranians are identified as Zoroastrians and accepted as Parsis by their possession of the sacred Sudreh and Kusti and knowledge of prayers and not by their ancestry. Why don’t Parsis in India have a similar system of identification? Today, modern Parsis are not distinguishable by their dress.

Prochy N. Mehta is a daughter, mother, wife, grandmother, school leader and highly accomplished sportsperson. An Asian record holder in sports, she was also the first female president of the Calcutta Parsee Club. She is actively involved in several companies including the business started by her father Rusi B. Gimi, eminent social worker and pioneer in outdoor advertising in India.

Extracted with permission from ‘Who is a Parsi?’ by Prochy N. Mehta, published by Niyogi Books. The book is available at Starmarks across Kolkata and on Amazon