Peak performance. At the recent glistening awards evening to commemorate 30 years of the existence of CIMA — Centre of International Modern Art — the high-octane Sapphire Creation dances that started and ended the event saw the honouring of personalities from the world of art. Lifetime achievement awards were conferred on Ruby Palchoudhuri, a living legend in the resuscitation and facilitation of craft; Alka Pande, art historian, author, museum curator; and posthumously on Sushen Ghosh, visionary sculptor, topped off by author Kunal Basu’s pithy speech. It talked of the ravages of conflict all around us, and in that context, brought in the dove of peace painted by Picasso. When the artist had said: “I stand for life against death. I stand for peace against war. Art stands for peace against war.” And so, Basu saluted CIMA for waving the flag of humanity in these dark times.

And humanism and social realism are amongst the many aspects that pique our interest at CIMA Gallery, Kolkata, where 12 Masters are being showcased over a period of three to four months, beginning December and culminating on April 13 this year.

What’s different about this show?

The intent, possibly, is to give aficionados a chance to have close encounters with chosen artists at a leisurely pace. The challenge, surely, has been to be able to club artists from different genres and art altitudes. Diverse in timelines, styles and mediums.

The director and curator of CIMA, Rakhi Sarkar, spelled out her approach succinctly, saying that the grouping was done “along the path of ideas” — by dividing the exhibition into three phases. And to “re-contextualise earlier investigations in a new light.” The thought was to “broaden the ambit and provide the generation of today with an opportunity to witness and experience visual history as it evolves shapes and unravels new territories.”

Rakhi Sarkar speaks at the inauguration

Phase One is titled ‘From Fantasy to Subliminal’, with a huge collection from Ganesh Pyne, Arpita Singh, Shreyasi Chatterjee and Sushen Ghosh. The next tranche, ‘From Neo-Realism to Social Realism’, embraces artists like Bikash Bhattacharjee, Jaya Ganguly, Jogen Chowdhury and Meera Mukherjee. And in the final phase with its title ‘Towards the Personal’, we will see the works of Lalu Prasad Shaw, Sanat Kar, Sarbari Roy Chowdhury and Somnath Hore.

Phase One in focus

It is Phase One we are concerned with at the moment, as it will be on till the 20th of January. The unusual choice of works gives it particular heft. Having done a pre-exhibition parikrama, it has been a chance to immerse oneself in the vast space that Ganesh Pyne occupies. Familiar as we are with Ganesh Pyne’s captivating tempera on paper and tempera on canvas works like Night of the Merchant, Man with Corpse and The Pitcher (innocent girl oblivious of a lurking predatory beast) done in the 1980s, it is his jottings that call for close scrutiny. As do the Metiabruzer Nawab Series, which brings out aspects of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s life, in his exiled Metiabruz.

A one-off fanciful cartoon appears unexpectedly, which is from his artistic time in the 1950s, when Pyne joined an animation company – really to earn some money. He was inspired by Walt Disney’s animations. And that impacted his mainstream work later on. Inspiration and influence came particularly from Abanindranath Tagore. As also from Rembrandt and Paul Klee. Impetus, too, from the masters of European cinema.

Part of The Metiabruzer Nawab series, by Ganesh Pyne

In the current exhibition, there are some classic works based on the epics, on canvas, and also using charcoal, crayon and pastels, mostly done between 2009 and 2010. The Mahabharata series admirably depicts The King — the sightless Dhritashatra; Parshuram; the Last Days of Vidura; the Charioteer; Bhimsen and Ghatothkatch. We also get his take on Abhishap, Narak and of the Demon at War — deep, dark, devolved. Observe his mixed media on paper and tempera on canvas Durga series done between 1986 and 1990. In his tempera on canvas, ‘The Wooden Horse’, Pyne himself makes an appearance. And to go back to the 1960s, there is an untitled work — a watercolour — which disturbingly shows a coy woman playing chess with a demon.

While viewing Ganesh Pyne’s artistic oeuvre, one will come upon the sculptures of the late Sushen Ghosh, less celebrated, but giving a serendipitious sense of the cerebral that impacts you. Those who have not had a chance to view Sushen Ghosh’s abstractions are taken up with the amalgam of the musical and mathematical, with their deep meditative undertones. Speaking to his daughter, Mahua, we find that the musicality was ingrained in the artist — he played the flute with competence — and titled his own creations as Frozen Music. She emphasises the play of rhythm in his sculptures, where physics, philosophy and geometric calculations imbue it with a multiple tonality.

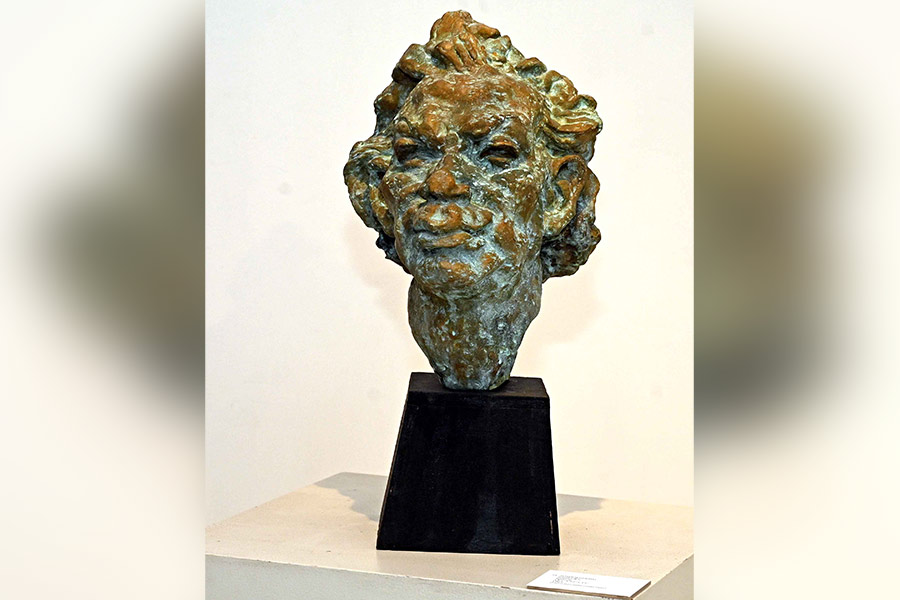

A masterly bronze head of Ramkinkar Baij, by Sushen Ghosh

Some of the Sushen bronzes on display: Within and Without, where his daughter finds the outer world coming into the inner world, rhythmically; the Monument of Lines, a diptych that is perhaps not monumental in size, but speaks out loud in the sheer strength of its spatial sensibility. And a masterly bronze head of Ramkinkar Baij, one of Sushen Ghosh’s mentors in Santiniketan (the others being Benode Behari Mukherjee and Nandalal Bose). His terracotta sculptural installations are unique at this exhibition.

Two women artists – Shreyasi Chatterjee and Arpita Singh – give new perspectives with their singular approaches to complete the quadrant at the first leg of this exhibition.

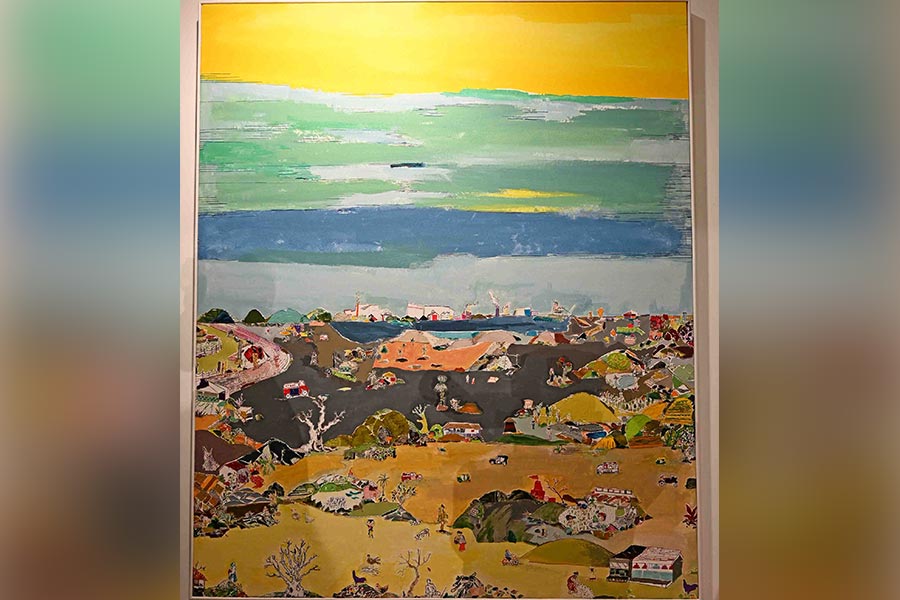

Not for Shreyasi Chatterjee the socio-economic concerns that bedevil many artists. Instead, her canvases become the storyteller’s tool to create whole landscapes where the stitches are her lines and the needle is her brush. Fanciful and quirky and detailed and inclusive of a whole village or city. At the entrance of the exhibition is this massive missive from Shreyasi, termed the Walkabout. This 70.5”x59.1” canvas done in 2008 incorporates all the elements that she works with — acrylic, water colour, embroidery, fabrics, appliqués and the use of Derwent pencil. It is, in her own words, a “mindscape.” Looked at from a distance, it is a painting, and on closer scrutiny, the detailing captivates.

A work by Shreyasi Chatterjee

The “baggage” of being an art history professor does not intrude on her creative process which amasses a range of drawings, water colours, sketches, kantha stitch, pen and ink on paper. And she brings a miniaturist technique into some of her work, which is contemporised. In her minute observation of landscape — life goes on, engulfed by colours and space divisions. One set is organic and the other architectonic — a symmetrical showing of urban scapes. The canvas Coexistence (temples and mosques) is an instance of her architectural perfection. As are her Urbanity series done with pen and ink on paper. Stop by the Sunflowers to see how she incorporates French knots to represent the disc florets in the centre of a sunflower. Observe, too, her own ‘Poshak’, her Kitchen Diary photographed during Covid, her imagination running riot and her sense of fun and quirkiness kicking into seen and imagined scenarios spliced in with the oddities of a Chalantika Bhojanalay.

Arpita Singh’s Durga, in the garb of a widow wielding a gun and trampling a human underfoot, is a telling statement that greets you at the mouth of the exhibition. This Padma Bhushan-awardee has six decades of work behind her. Immersing herself in “finding her own visual language, she focussed on saturation of colour, form and texture. This single-minded process has marked her out as one of the most outstanding artists of post-Independence India,” says art critic Ella Datta.

Arpita Singh’s Durga, in the garb of a widow wielding a gun and trampling a human underfoot

CIMA has picked some of her key representational work from her etchings of the 1980s, to her thought-provoking watercolours on paper (1999) with the woman in defensive mode dominated by the male; from her oil on canvas creations (‘Munnapa’s Golden Mantle’; ‘The Inheritance’ which was painted in reaction to a play that aroused this imagery) to the range in 2000-2023 — there is plenty to ingest about her experimentation with lines, colours, texturizing, employing a constant intuitive streak.

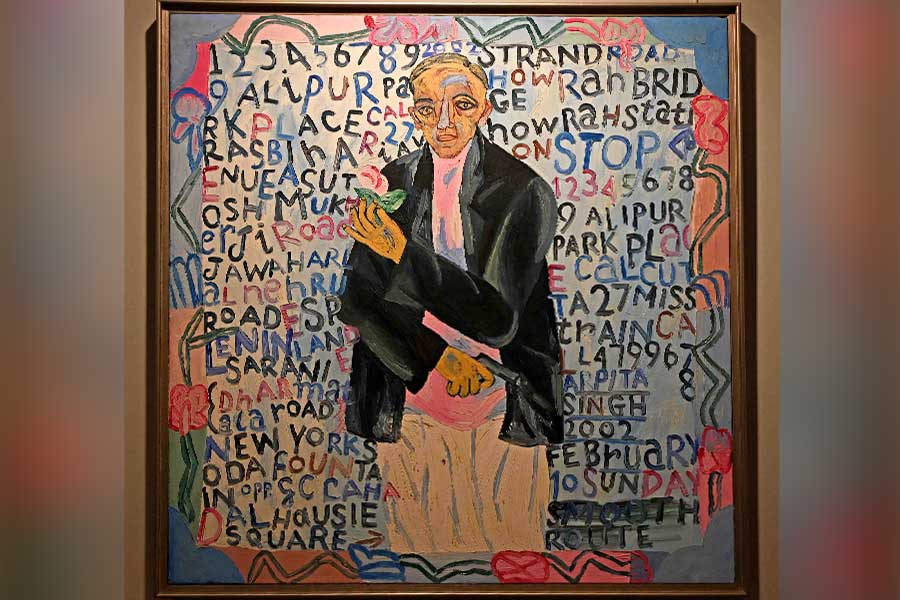

One very interesting aspect is Arpita Singh’s imbibing of the patachitra style — showing her mastery of her medium, craft and form, which has been given a contemporary twist. Many people were intrigued by the visual of the invitation card — looked at closely, the borders are inspired by patachitra. An oil on canvas, which is titled ‘Smooth Route’, depicts a man holding a gun in one and a rose in the other, the lettering and numbering adding to the visual imagery.

‘Smooth Route’ — oil on canvas

We direct the viewer to the composite “Ocean Dream” (occasioned apparently by the Syrian refuge crisis), ‘What Took You So Long’, ‘Pink Pillow’ and ‘Woman Changing Clothes’ (the last mentioned showing a gloved hand from the side, pointing to the wording ‘Teach Her the Hundred Virtues of the Day’).

There are also her purposefully misshapen women, childbearing women, and dominant men, all in the area of the phantasmagorical. Open to your interpretation and revalidation.

The exhibition’s first part is open till January 20.