How can credit cards be made more secure, solar cells more enduring, MRI scanners more accurate and GPS more reliable? The answer lies in investing in and developing quantum technology, which regulates all these and much more.

For decades, India has huffed and puffed when it comes to creating a state-of-the-art infrastructure to make the most out of quantum technology. But with the launch of the National Quantum Mission in April, with an outlay of Rs 6,000 crores, India is finally aiming to take a quantum leap. To be implemented between 2023 and 2031 by the department of science and technology of the Government of India, the Quantum Mission will involve collaboration among several premier research institutes across the country. Prominent among them, as one of the main players in the project in east India, is the S.N. Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences (SNBNCBS), based in Salt Lake.

‘The question is which country will become the Taiwan of quantum technology’

Tanusri Saha Dasgupta (left) and Manik Banik play an integral role in the National Quantum Mission on behalf of SNBNCBS Pramanik

Established in 1986 to honour the legacy of Satyendranath Bose, the mathematician and physicist after whom the bosons (a type of subatomic particles) are named, the S.N. Bose Centre conducts research in quantum technology, astrophysics and material physics as well as chemical and biological sciences. Situated on a 15-acre, lush-green campus, the S.N. Bose Centre has a team of more than a dozen scientists who specialise in the quantum field, assisted by hundreds of PhD and postdoctoral scholars. “There are four pillars of the Quantum Mission — quantum computing and simulation, quantum communication, quantum sensing and metrology (the science of measurement), and quantum materials. Our expertise is mostly concentrated in quantum communication and quantum materials,” says Tanusri Saha Dasgupta, director, SNBNCBS, who joined the institute as a faculty member back in 2000.

Saha Dasgupta explains that while standard bits fit into the binary of either zeros or ones, quantum bits (called qubits) can exist in several possible states at once (called superposition) and exchange information with other particles (called entanglement). “With qubits, you can’t say for certain whether something is this or that. It’s a bit like Sukumar Ray’s Hasjaru,” she adds. Or, as the more conventional analogy goes, the thought experiment that is Schrodinger’s cat. According to her, quantum technology is hovering roughly where semiconductors were in the 1950s, in the sense of its untapped potential to transform lives. Over the second half of the 20th century and the first part of this, semiconductors have become one of the most sought after materials on the planet. Without it there would be no iPhones and, potentially, no tension between the US and China over Taiwan, either. “Taiwan wields such immense geopolitical influence because nobody can make semiconductors the way they can. As of now, there’s no alternative to manufacturing semiconductors without using silicon. The question is which country will become the Taiwan of quantum technology,” asks Saha Dasgupta.

‘Once we’ve hit 50 qubits, we’ll know what it takes to scale faster’

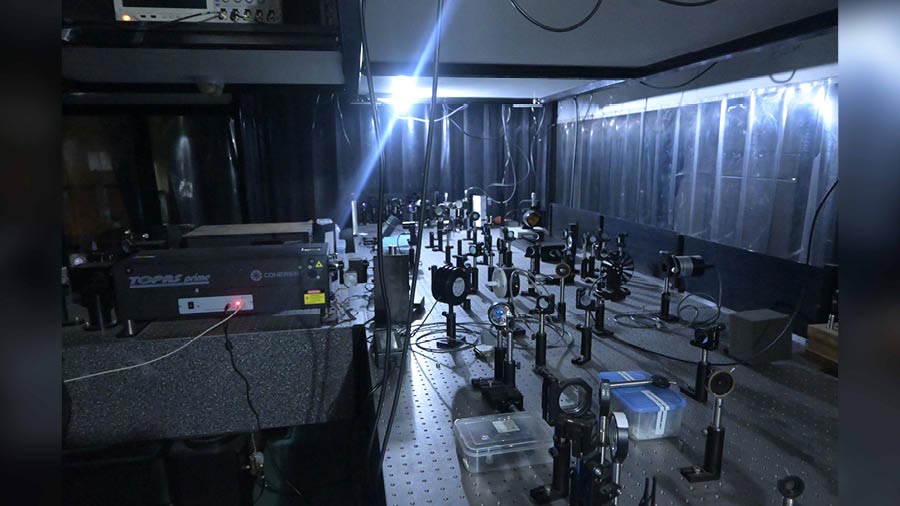

SNBNCBS has state-of-the-art facilities relating to research on different aspects of quantum communication and quantum materials Pramanik

India’s Quantum Mission intends to create an innovative ecosystem for quantum technology in the country. To this end, the early deliverables include developing quantum computers with a minimum of 20 to 50 qubits capacity within the next three years, before scaling it to somewhere between 50 and 1000 qubits by 2031. “Creating the first 10 to 50 qubits is the hardest. It not only requires extreme levels of precision, but we also have to be careful that the qubits are interacting properly. Once we’ve hit 50 qubits, we’ll know what it takes to scale faster,” says Manik Banik, who joined the S.N. Bose Centre as associate professor last year. Banik feels that the Mission needs to create a “skilled workforce of quantum handlers, who, in the long run, can save a lot of energy and cost through their contributions to quantum computing”.

Everything from healthcare to air traffic regulation to digital multi-tasking and computation can be enhanced by quantum technology. Quantitatively, the Government of India estimates that the Quantum Mission can inject a further $280 billion to $310 billion into the Indian economy by the end of the current decade. Alongside, it should also boost other priority schemes such as Digital India, Make in India, Stand Up India and Skill India, while also helping India attain the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). “A lot of scientific research and decision-making today revolves around simulations. We first simulate a lot of options within our own framework of permutations and combinations and then choose the best possible ones. This simulation is something that can be taken to the next level with an acceleration in quantum technology,” says Banik.

‘It’ll be a revolution brought about by joining hands’

For India’s Quantum Mission to be successful, several stakeholders have to work in cohesion TT Archives

The Quantum Mission declares India to be a part of an “elite club” of seven countries that have a dedicated quantum project at a national scale (the others being the US, Canada, Finland, France China and Australia). But Saha Dasgupta issues a reminder, saying: “A lot of other countries are also putting in a lot of time, money and resources towards quantum development. The European Union (EU) is a great example. Even among the nations mentioned by the Mission, those like the US are way ahead of us. Companies like Google and Microsoft have been pouring mind-boggling sums into quantum computing. India is lagging behind, but at least we’re getting a move on thanks to the Mission.”

While the exact structure and scope of the Mission is subject to constant scrutiny and change, the groundwork is underway. Saha Dasgupta clarifies that this is a complex undertaking requiring collaboration at different levels, since there will be a chain of command with multiple committees coordinating everything. “With time, the Mission will be broken down into stages, each of which will have its own objectives. There will be failures along the way, as is natural. Gradually, certain ideas will be incentivised and accepted and things will take their own shape,” she says.

Alongside the S.N. Bose Centre, Saha Dasgupta acknowledges that there are other stakeholders connected to the mission in West Bengal: “There’s the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science as well as the Bose Institute, among others, that have a crucial role to play from this part of the country.”

Going forward, Saha Dasgupta is optimistic that India’s quantum potential can be unlocked with the “right balance between quality and quantity”. As with any project of such magnitude, progress will take time, with change happening in crests and troughs. But if there is anything that can be guaranteed right now, Saha Dasgupta thinks it is this: “The entire country will be connected in working towards quantum development. There will be centres such as ours, and then there will be spokes and spikes. It’ll be a revolution brought about by joining hands and working together.”