It’s that time of the year again. When we reach out once more for that ready reckoner for all things auspicious. The numbers are dwindling, yes, but there are still those who swear by its content, revised and reconfigured every season in keeping with the stars above. When to propitiate the gods for the clemency of heaven; when to plan a wedding, or a newborn’s initiation into the world; even when to embark on a journey, that exact moment when personal destinies and impersonal planets would be in perfect sync, or so they claim.

Sounds familiar? Of course, it does. It’s a familiar book with a familiar cover, the whole year ahead compiled and compressed into one handy volume with a shared nomenclature. Bengalis call it the panjika, the astronomical almanac most homes would have looked up sometime or the other, for earthly advice or celestial remedy. For the god-fearing Bengali Hindu, it’s their spiritual lodestar.

Now that the first day of the Bengali New Year is here — April 15, according to the 2022 Gregorian calendar — it is time perhaps to step back in time to trace the origins of one such almanac, the Gupta Press Panjika. The almanac, published by Gupta Press, has been inextricably linked to Poila Baisakh celebrations since it was first published a century and a half ago; 153 years to be exact.

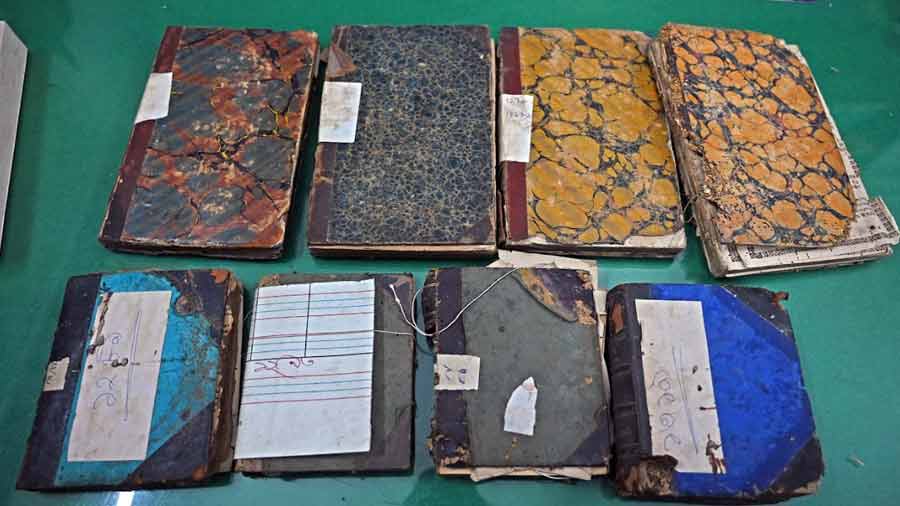

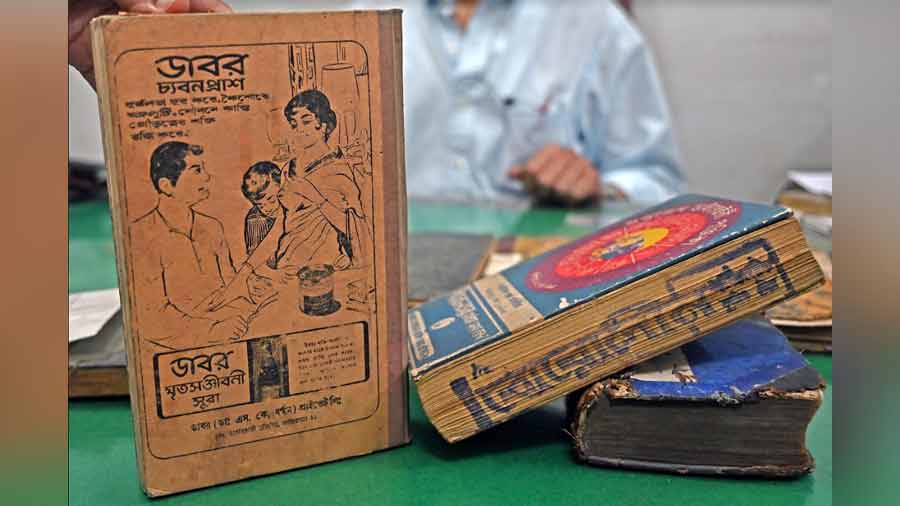

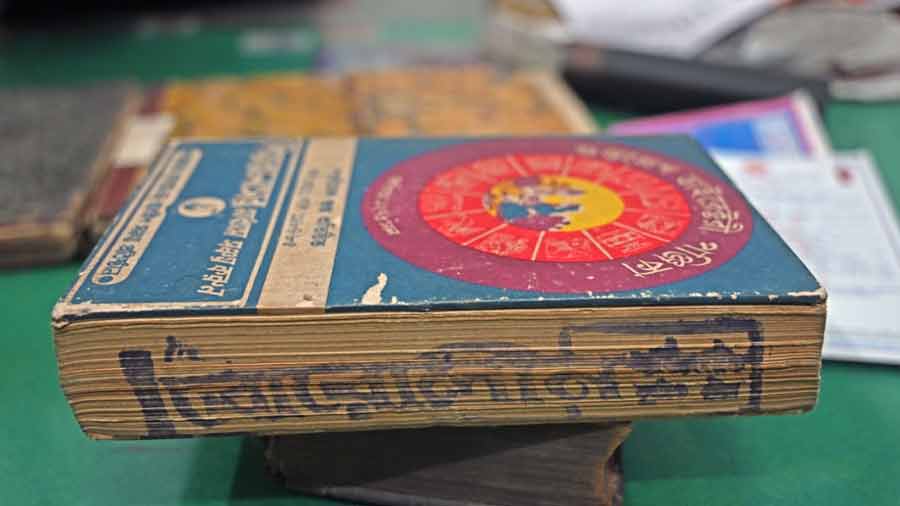

Panjikas from previous years

Several other popular almanacs are available too — publications like Shri Madan Gupter Full Panjika, PM Bagchir Directory Panjika, Beni Madhab Siler Full Panjika and the Bishuddha Siddhanta Panjika — but none has pervaded the Bengali consciousness in the way the Gupta Press Panjika has done. Here’s a brief history then, for those interested in its provenance.

The beginnings

The story of this Bengali almanac begins with Durgacharan Gupta, a businessman who founded the Gupta Press in 1861 at 16, Mirjafar’s Lane in North Kolkata. Eight years later, in 1869 — 1276, according to the Bengali calendar — he would publish the first edition of the Gupta Press Panjika. The same year the press would shift to a new address, at 24, Mirjafar’s Lane, before scarcity of space would prompt another change of location, in 1879, to 221, Cornwallis Street. The press is now located at 37/7, Beniatola Lane.

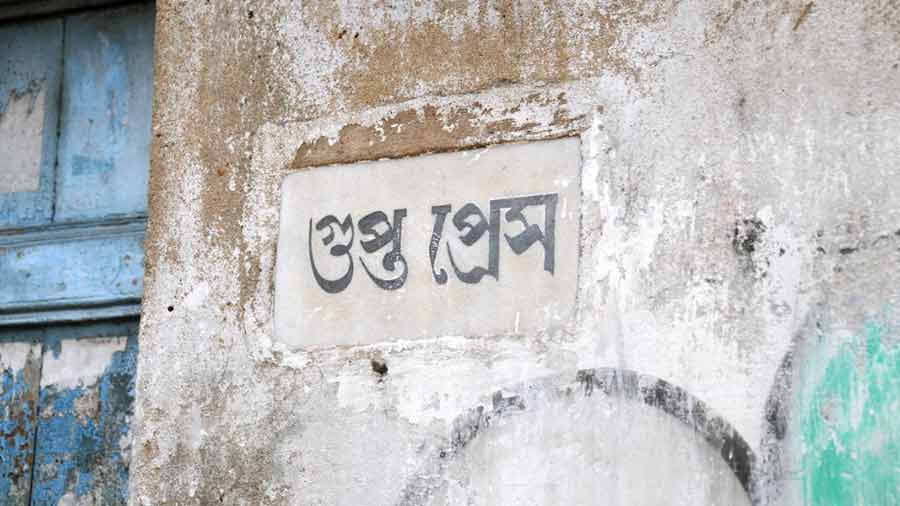

The press is now located at 37/7, Beniatola Lane Ashim Paul

Apart from publishing the almanac, Gupta Press printed a wide collection of other books, among them Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Lalita O Manas and Rabindranath Tagore’s Bonophool. The press would print books of different genres, from dictionaries and textbooks to books on medicine and even ‘Bottala’ literature, slim volumes of 8-10 pages written on topical issues of the day.

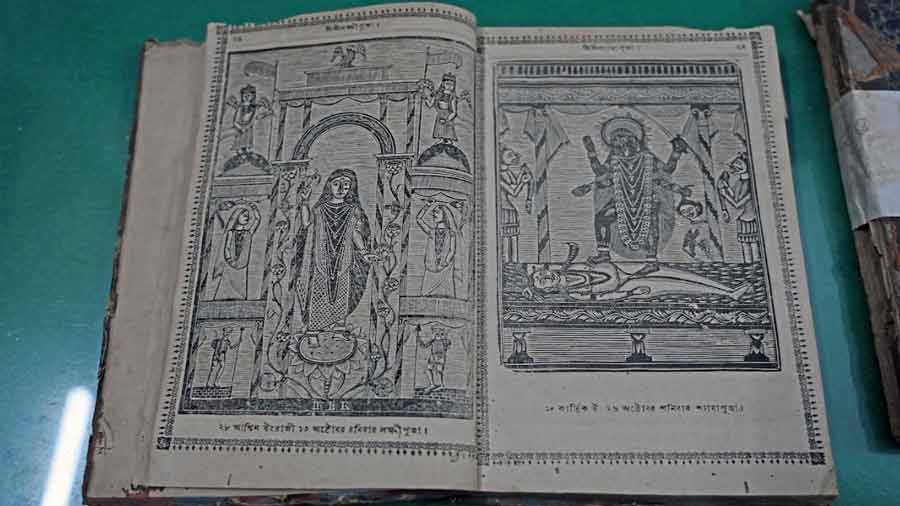

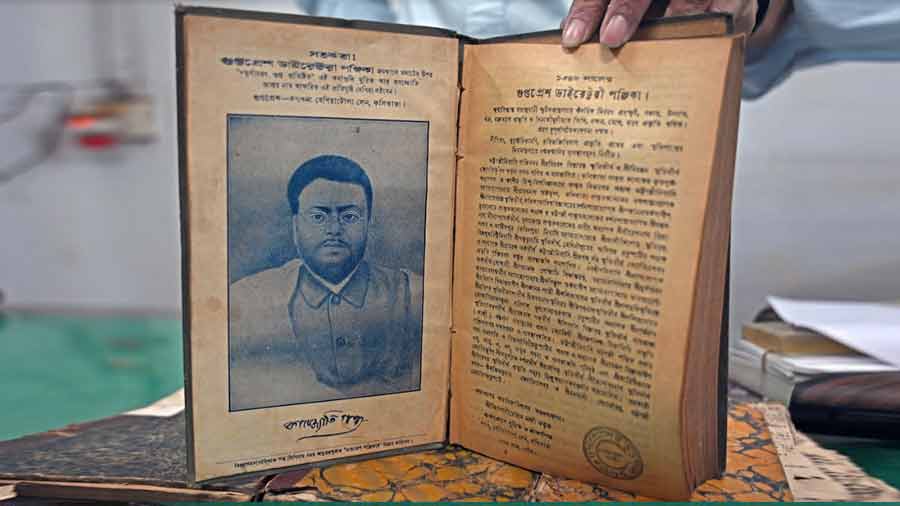

Pages from the almanac Amit Datta

One of the works Gupta Press printed was by Durgacharan’s wife, Kailashbashini Devi, an important figure in Bengali literature. Her book, Hindu Mohilagoner Heenabostha, is a commentary on the position of Hindu women in the Bengali society of those times.

The press also printed periodicals and magazines, such as Sahitya Ratna Bhandar and Sudhakar, but it was the panjika that ensured its lasting popularity.

The panjika would come in handy in other ways too. Durgacharan had started a business in dheki, a husking pedal used to separate rice grains from their outer husks. The business did not succeed but Durgacharan was not one to sit back and rue his failed venture. In the panjika edition of 1888, he published an advertisement to sell off the husking machines.

First medium of advertisements

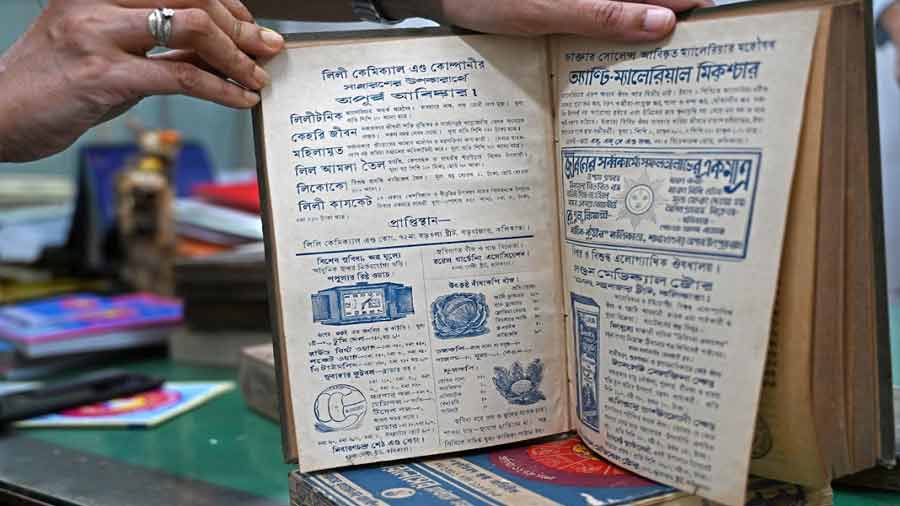

Examples of early advertisements in the almanac Amit Datta

The panjika, in fact, would often carry advertisements as Durgacharan, hardly a man to rest content with printing books, broadened his interests and got into promoting the publication business. The ads would mention the availability of machines and materials, which he would provide. Durgacharan would also train budding entrepreneurs on how to start their own businesses.

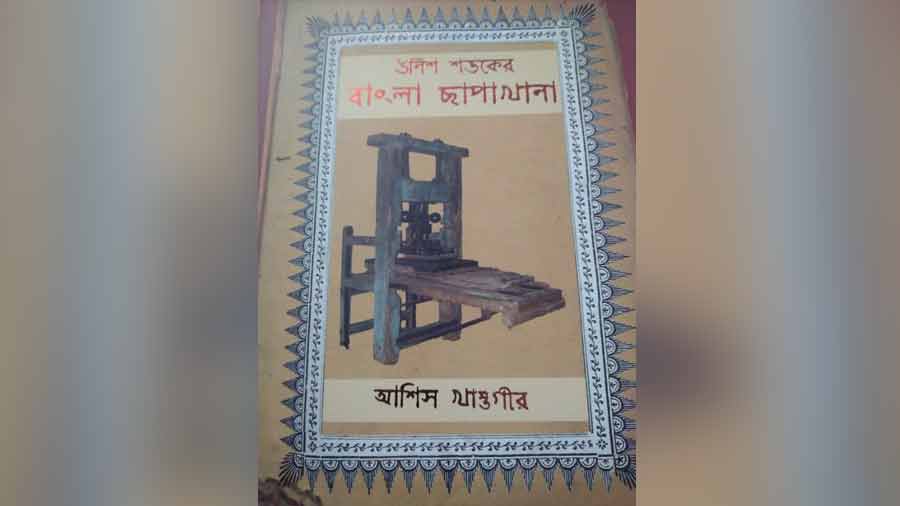

Asish Khastagir, author of Unish Shotoker Bangla Chhapakhana, has cited excerpts from such advertisements in his book, an account of Bengali printing presses of the 19th century.

“Amader nikot karjoupojogi teen prosto press o soronjomadi prostut ache (We have a set of three press machines and other machinery suitable for work)…,” reads an excerpt from an ad the Gupta Press Panjika had published.

The cover of Asish Khastagir’s book Amit Datta

The entrepreneur in Durgacharan had not only gauged the mind of the religiously inclined Bengali but also figured out early the reach of the panjika. Today, panjikas, as a form of publication, are not merely codified books on ceremonies and ephemeris rolled into one or a Panchang — as they are often referred to — but also carry a wide range of advertisements, the legacy of a man who set up a printing press at Mirjafar’s Lane many years ago.

Indeed, the panjikas — or panji, as they are known colloquially — were the first publications to carry advertisements and soon emerged as an indispensable medium for effective promotion of products. The range was wide — from medicinal herbs to controlling bugs and magical rings that promised a cure for every possible affliction. Astrologers too put in advertisements, promoting themselves and their ability to decode the future. Among other products and brands advertised in panjikas were saris, Boroline, the all-purpose antiseptic cream, and the battery-maker Exide.

Advertisements for Dabur and Boroline on the 'panjika' Amit Datta

Durgacharan’s business successor, Gyanprakash Gupta, would later start the Gupta Press Agency. But the business by then had become so widespread that it was difficult to take care of it, mentions Khastagir. After Gyanprakash, the whole business was inherited by Durgacharan’s son Jagatjyoti Gupta. The press was eventually auctioned off around 1920, when Nripendranath Bhose, a lawyer by profession, bought it. It was around that time the press shifted to its current location at 37/7, Beniatola Lane.

A photo of Jagatjyoti Gupta Amit Datta

Erudite and versatile, Nripendranath was involved with most of the sporting bodies of his time, including the Olympic association, as well as the Scout movement in India. He was clearly a busy man, a possible reason he never came to the forefront of the publishing business. The Gupta Press Panjika retained its name and its charm.

The legacy continues

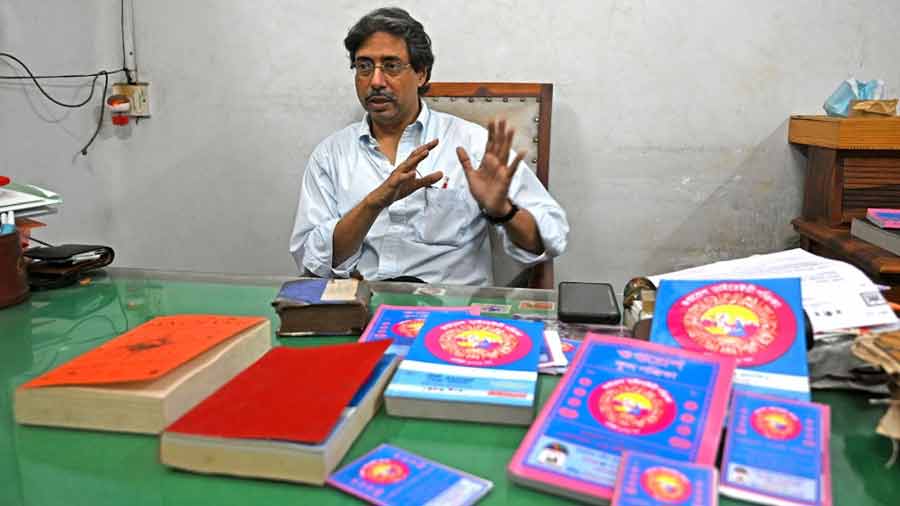

After Nripendranath, his son Ajoy Kumar Bhose would inherit the family business. That would be in the late 1940s, sometime around Independence. “My dadamoshai (maternal grandfather) Ajoy Kumar, Nripendranath’s son, took care of the publication for more than 51 years. He passed away in 1998 at the age of 86,” says Arijit Roy Chowdhury, the current managing director of Gupta Press.

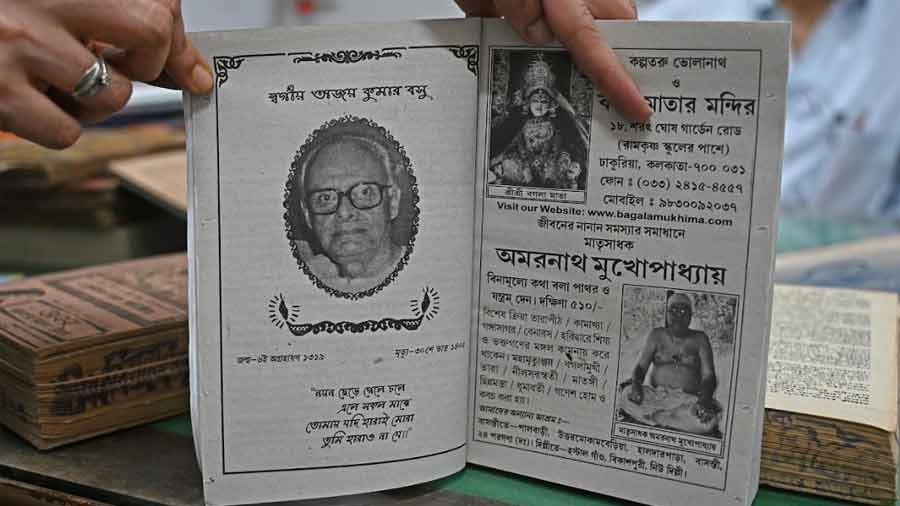

Ajoy Kumar Bhose took care of the publication for more than 51 years Amit Datta

Arijit had joined the business in 1985. His grandfather, by then in his seventies, wanted to groom the young man for taking over the family business. It was, in Arijit’s words, a “big leap” for him. “I was in college then, completing my BCom from St. Xavier’s, when I was asked to take charge of the business. I would visit the press in my school days but never did I imagine that I would join it one day. Taking charge of a publication like the panjika was a big leap for me. I had to take care of all the aspects of the almanac. Starting from the editorial (which mainly covers the calculations, or gonona, done by astrologers) to production, marketing, circulation and distribution, I had to supervise everything,” he says.

Arijit Roy Chowdhury joined the business in 1985 when his grandfather wanted to groom a young man to take over the family business Amit Datta

It would have been a tough rite of passage for the college student, hardly prepared for the responsibilities that had suddenly been thrust upon him. But Arijit picked up fast; business was in his genes. He has even written a book in English named Panchang: Your Guide to the Hindu Calendar and What It Foretells. Ajoy Kumar had chosen well. The legacy he had passed on was in safe hands. Not only that, it was evolving too — in tune with the aesthetics of change.

Changing with the times

When products are similar in content, appearances do matter. The Gupta Press Panjika too would change its appearance, from a black-and-white cover to pink with a black logo. That too would change after artist Shuvaprasanna introduced different shades of pink and blue.

The panjika’s size too has varied at different points in time, the main reason for such changes being the volume of content and sometimes the high price of paper. In the 10 years from 1935 to 1945, the panjika would be published as a small book. It would later metamorphose into a long and thin book, before stabilising to mainly two versions, a full version and a half.

The full version is like a directory that includes directives on how to conduct pujas and other daily rituals. The directives are absent in the half version.

Bengali almanacs are based on two types of calculations — the Surya Siddhanta and the Bishuddha Siddhanta. Gupta Press follows the Surya Siddhanta system. Pandit Achintya Bhattacharya does the calculations for the almanac, continuing a family legacy that began with his grandfather, Shyamacharan Kobiratna.

The full version is like a directory that includes directives on how to conduct pujas and other daily rituals Amit Datta

Gupta Press has also come up with a newer pocket-friendly version of the panjika, another necessary adaptation to keep up with the fast pace of modernity.

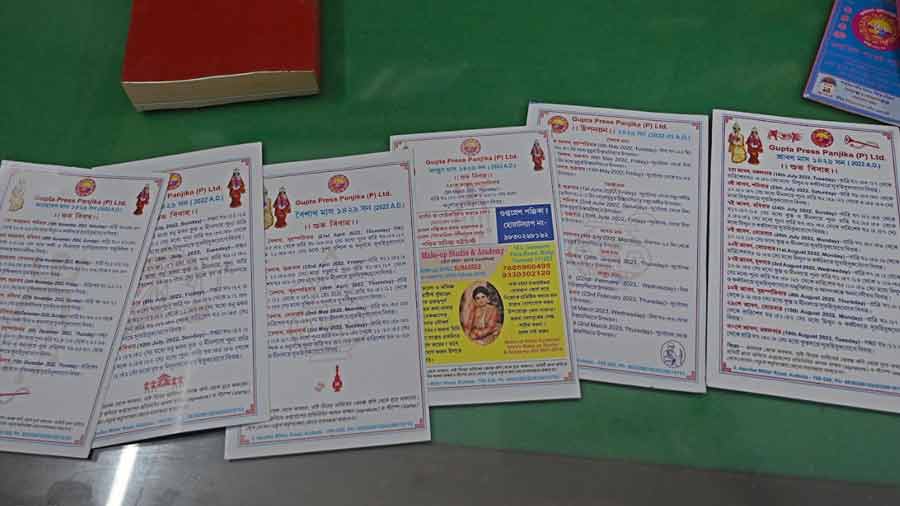

Among other items the press prints are cards for weddings, rice and thread ceremonies and housewarmings. These cards, especially the wedding cards, are quite popular. They come with a WhatsApp number — 9830268162 — where potential customers can place orders. Payments can be made online.

Date cards for different occasions Amit Datta

A few years ago, the 153-year-old press went a step further in updating itself. The entire panjika was made available in the form of CDs and DVDs. The panjika can now be accessed even in PDF format.

Despite evolving with the times, Gupta Press faces an uncertain future as the next generation is not interested in taking up the family business. “This business requires a lot of expertise. Knowledge of astronomy and astrology is required but the next generation does not have the will or patience to learn,” Arijit says.

Unfortunately, the ready reckoner has no remedy for that.