‘It’s Ramzaan!’

I have heard these words from the time I could scrape through a fast or two without my parents being hauled off by the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

I may have left Mission Row Extension 25 years ago but these are some of the memories of a lunchless month from that part of Kolkata:

- Sleep displacement over food deprivation. I can endure an absence of drink for hours after sunset, but if there is something that stretches me more than hunger, it is the smartphone alarm getting me abruptly out of bed at 3.05am for nutritive restocking. I intend to submit a petition: ‘O Allah, would thy angels permit me a late night every night, so that I may refill at 11.30pm but sleep uninterrupted until 5.25am?

- The guilt of being respected and admired for remaining drinkless or foodless in an air-conditioned office ordering people around when there is a rickshaw-wallah plying his load (‘khuraaki’) somewhere in Damzen Lane, Madan Street, Zakaria Street or Weston Street in the noon boil without a whisper of complaint.

Shutterstock

- The memory of batting on the Maidan during Ramzaan without seeking the services of a runner (what if he got me run out?), being dismissed after an hour, returning to the ‘pavilion’, taking off the shirt, dousing the head with water brought specially from home and crashing out — not as much to catch up on lost night sleep as to escape the conscious memory of a dropless throat. Since I have not felt that thirsty in decades, I have progressively discounted the value of my Ramzaan experience as ‘no big deal’.

- The energy spike of the first three weeks on an empty stomach when I can get more done in the office (without sleep in the afternoon) followed by a visible slowing down in the last week. I intend to submit a message of gratitude: ‘O Allah, thy supplicant bows to thee that thou in thy wisdom limited the number of fasts to 30.’

- The emergence of an entire family of words related to the Ramzaan experience — starting from ‘chhelli khatmi’ (the final conclusion) that was supposed to be used for a brief vacation or feast on the weekend before Ramzaan commenced (quite like the Carnival in Rio de Janeiro before Lent without the scale, music and anyone taking their clothes off). Then one year in the Seventies, a bus carrying a partying group had an accident on the outskirts of Kolkata and thereafter this revelry was superstitiously abandoned.

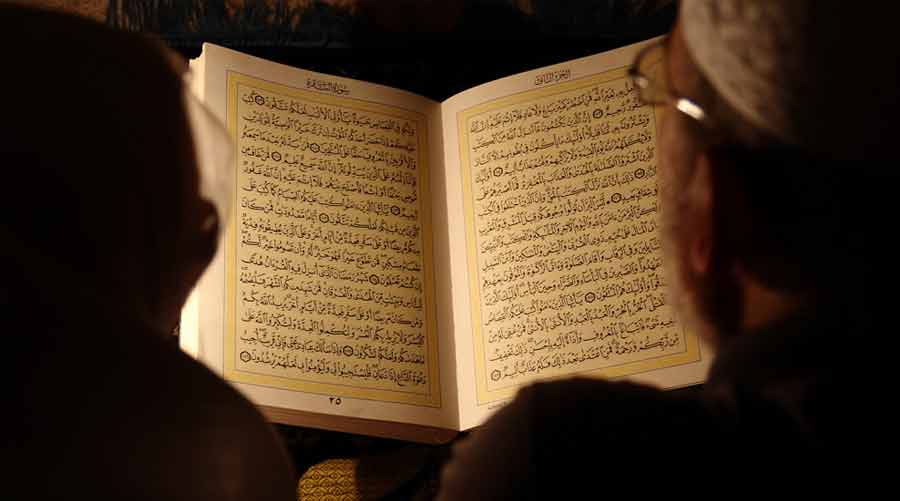

- The obsessive need to pack in as much bookish piety in the hope of generating a 70-fold return from Allah on the Day of Judgement. I have known of individuals reciting the Holy Book for hours with the objective to finish the entire Quran word by word in just a couple of days, then starting all over again — and telling us without the hint of a brag ‘It’s not like it used to be…could complete only 12 complete khatams (recitations) this year’.

@itsme_Ramsha/Instagram

- The emergence of a distinctive school of cuisine only for these 30 days before they are dismissed and never discussed again — the yellow lentils with a squeezing of overhead lemon that we refer to most uncreatively as ‘daal’; the interwoven layers of ‘chilla’, bread and vegetables drowned in dahi that we refer to as ‘sufoot’; the throat-lubricating dahi vada peppered with red powder; the fried bhajiya that threatens nutritive defences and the chanaa in imli ka barbat. The core memory of food abstinence in Ramzaan is counter-balanced by gastronomic variety and excess following sunset.

- The gradual phasing out of the word ‘Ramzaan’ with ‘Ramadan’ in India, which is like telling the faithful of this country that ‘Please wake up and become aware that this Wahhabi-ised version is better that your casual Persian influence you unmindfully practised for centuries’.

- The trappings associated with Ramzaan that extended beyond the core piety — the linen-covered trays of food that maids carried on their upturned palms above their shoulders from one fasting home to another through Bandukgully; my mother putting a heavy fragrance into our prayer clothes around simmering Yemeni incense sticks (‘bukhoor’); my mother preparing a boxful of dry fruits to be consumed periodically by children through the night of Lailatul Qadr when everyone is expected to remain awake until the bottom arc of the sun has finally cut above the horizon.

- The emergence of the ‘iftaar party’ as a social institution graced by political heavyweights where Muslim hosts and non-Muslim attendees are forever posing for group pictures or hugging each other, making me wonder how they get the time or the himmat to do all this after fasting for days.

- The exchange of gifts during the first 10 days of the month with a card that says ‘Dua ma yaad’ (working on the assumption that all prayers are indeed answered during this 30-day window), which on WhatsApp has, over the years, been unromantically abbreviated to ‘DMY’.

- The overload of ‘Ramadan Kareem’ WhatsApps during the early days of the month and a tsunami of ‘Eid Mubarak’ messages with crescent moons and minarets designed into them when the month is finally over.

- The demand of office colleagues, who could scarcely have been concerned about a poor office colleague remaining hungry day after day, now demanding ‘Biryani’ on Eid (‘Ki guru, khaoaabi na?’).

- The resigned response of the faithful who discovers that 1.5 kilograms have been added through the month, inspiring a new hope ‘There is always the next Ramzaan to correct things, inshallah!’