Our world, or more precisely, our physical world is not the same anymore. Over the last century there has been a drastic reduction in the range of motion that our joints and muscles are subjected to. According to Michael Clark and Scott Lucett (National Academy Of Sports Medicine, US), human beings “have been physically moulded by furniture, gravity and inactivity”.

Readers of this space can recollect what a huge advocate I am of the primal pattern movements in daily life. However, the continual decrease in everyday activity has slowly reduced our ability to perform the primal movements effectively and contributed to many of the postural defects that we see in people. The consequent muscle imbalance and poor joint mobility coupled with poor lifestyle choices is the main reason for poor metabolic health and musculoskeletal pain in today’s society. Foot and ankle injuries, low-back pain, knee injuries, shoulder pain and neck/upper back are like an epidemic in today’s world. This new movement-starved environment produces more inactive, less healthy and nonfunctional people who are more prone to injury. This also carries over to the adolescent population with around 18 per cent of our urban adolescents and teenagers struggling with poor health and excess weight.

RATIONALE FOR CORRECTIVE EXERCISE

Despite being at the receiving end of a volley of criticism labelling me a “fear-monger” and an over-clinical zealot, I have continued my crusade for the need for corrective exercise in everybody’s life, particularly in the vulnerable population. Visit the orthopaedic ward of any hospital and you are likely to find that area overcrowded with patients, all of them looking for a solution to their problems. Ironically, the orthopaedic surgeon is not in a position to help them if the treatment option is not surgery. A surgeon is not expected to be an expert on rehabilitative or corrective movement patterns. And surgery should be only the last option for any musculoskeletal disorder. Alf Nachemsen, a pioneer in spine care and doyen of orthopaedic surgeons, was once known to have remarked that 80 per cent of all orthopaedic surgeries are unnecessary.

The average population has altered movement mechanics. Many of them join a gym with the best and most sincere intentions and soon discover that their bodies were never prepared for the movement patterns prescribed in the typical ‘gym scenario’. Unfortunately, many training programmes for conditioning the musculoskeletal system often neglect proper training guidelines and do not address potential muscle imbalances one may possess from a sedentary lifestyle. This can result in a weakened structure and lead

to injury.

Simply put, the extent to which we condition our musculoskeletal system will directly influence our risk of injury. The less conditioned our musculoskeletal systems are, the higher the risk of injury. Here is the irony — as our daily lives include fewer physical activities, the less prepared we are to partake in recreational and leisure activities such as resistance training, weekend sports like golf or tennis, or simply playing on the playground.

THE WAY FORWARD

The average gym and personal-training mindset is ill-equipped to handle the needs of today’s clients and athletes. The challenges of nonfunctional living demand a very different nature of skill sets from today’s fitness professionals. Health and fitness professionals need to be sensitive to the unique needs of the present population and gear up to address these movement deficits.

Clients and athletes also need to be conscious that they pick out only those exercise coaches who are qualified and trained to address movement deficits and dysfunctions. Today’s client is not ready to begin physical activity at the same level that a typical client could 20 years ago. Therefore, today’s training programme can’t stay the same as it was 20 years ago.

The modern mantra in fitness should be to create programmes that address functional capacity as part of a safe programme designed bespoke for each individual. Coaches should be alive to the environment, the required tasks, the individual muscle imbalances and movement deficiencies before designing an exercise routine.

Corrective exercise protocol is basically a protocol that attempts to identify a neuromusculoskeletal dysfunction, develop a plan of action and put in place an integrated rectification strategy. The three-step process is to:

1. Identify the problem (integrated assessment)

2. Solve the problem (corrective programme design)

3. Implement the solution (exercise technique)

PHASE 1: INHIBIT OVERACTIVE MUSCLES

Inhibit is the first phase in the Corrective Exercise Continuum. The goal of the inhibit phase is to reduce or modulate the activity of the nervous system that innervates the myofascial. It is essential to recognise that muscles identified as overactive (via the movement assessments) should receive inhibition techniques.

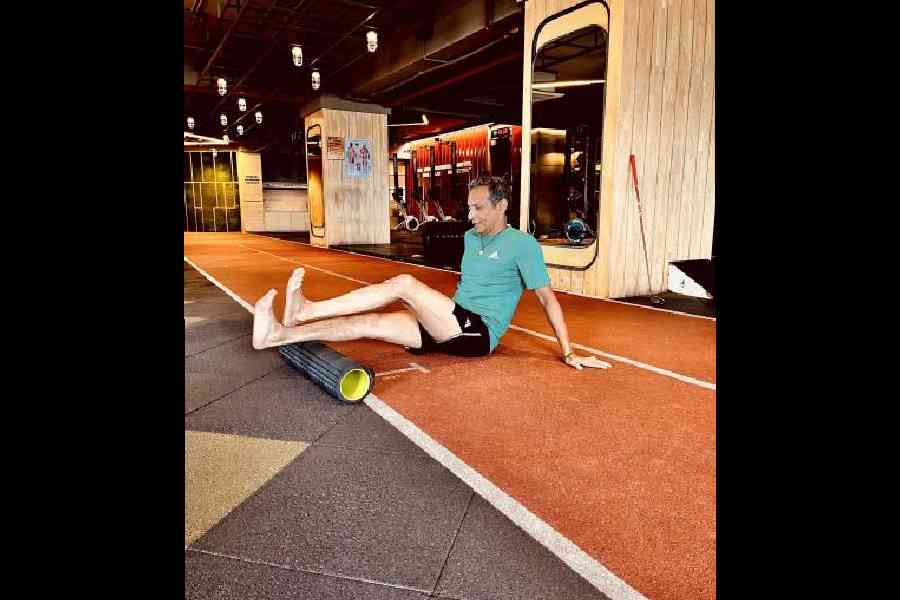

There are several corrective exercises to inhibit overactive muscles, such as foam rolling, percussion devices, or manual techniques like massage and instrument-assisted soft-tissue manipulation. However, many of these techniques require additional licensure. Thus, when it comes to corrective exercises, foam rolling is the most common for the Corrective Exercise Specialist.

The foam roller is thought to work via two primary mechanisms. 1) It affects local tissue dysfunction, and 2) It influences the autonomic nervous system. The ultimate goal of foam rolling is to prepare the muscle for phase two, lengthening, by improving local tissue mechanics and making the muscle more susceptible to stretching via afferent central nervous system (CNS) pathways.

Research supports that foam rolling before stretching leads to enhanced improvements in flexibility and joint range of motion.

PHASE 2: LENGTHEN (STRETCH) SHORTENED MUSCLES

Lengthening, or stretching, is the second phase in the Corrective Exercise Continuum. Contrary to popular belief, stretching does not stretch out muscle fibres. Lengthening refers to the elongation of mechanically shortened muscles and connective tissue via a nervous system response in which muscle spindle activity and motor neuron excitability are decreased.

Lengthening the muscle and connective tissue makes it more susceptible to forces, allowing better elongation, thus improving the range of motion. This is an essential aspect of stretching, specifically static stretching, for not only all fitness professionals but also athletes and general exercise population to understand.

While stretching does have a mechanical effect, such as increasing muscle compliance, as was just noted, the real benefit of stretching is a “psycho-physiological” effect through the increased stretch tolerance. Stated more simply, static stretching will “calm a muscle down”, allowing improvement in range of motion, improved length-tension relationships, force-couple relationships, and enhanced movement patterns.

Lengthening should only be performed on those muscles which have been identified as short and overactive. A common mistake is to stretch those muscles which feel “tight”. However, due to the response of certain stretch receptors, muscles that are long are more frequently described as feeling tight than those that are short. Therefore, it is imperative that you use the findings of the movement assessments to guide the corrective exercises to build into your programming.

It may help to think of phases one and two of the Corrective Exercise Continuum as the Mobility sections of corrective exercises. Both inhibition and lengthening are used before activation to improve tissue extensibility and joint range of motion before isolated strengthening. As Mennell (1964) stated, normal muscle function is dependent on normal joint movement.

PHASE 3: ACTIVATE UNDERACTIVE MUSCLES

The third phase of the Corrective Exercise Continuum is to activate the underactive muscles. Activation refers to the stimulation of underactive/lengthened myofascial tissue. While there are a handful of activation techniques available, from my personal hands-on experience, I have noted that isolation and isometric exercises work the best.

In this phase, the goal is to isolate specific muscles, and in some cases, to emphasise a particular part of a specific muscle, to increase intramuscular coordination and to improve force production capabilities. Intramuscular coordination is achieved when a muscle has optimal motor unit activation, motor unit synchronisation, and the optimal firing rate.

Similar to an intrastate highway, isolated strengthening is focused on one muscle and is not concerned with crossing over state lines into other muscles. Thus, the corrective exercises here are highly controlled and must be executed with precision.

An example may be activation of the gluteus medius for a client that demonstrates knee valgus, indicating an underactive gluteus medius. The exercise practitioner may prescribe exercises like a fire hydrant, side-lying leg abductions, and so on to create isolated strength in the muscle that will later on play an active role in integration.

Also, understand that this is simply a phase of training. Eventually, the training wheels will be taken off as the client becomes stronger and improves control. The goal will be to finally achieve competence in integrated movement.

PHASE 4: INTEGRATE WITH MULTI-JOINT MOVEMENTS

The last phase of the Corrective Exercise Continuum, integration, is when steps one to three are put into action. The first three steps of continuum have been equated to listening to individual instruments, while step four is listening to all the instruments playing together as a single integrated unit.

Phase 4 of corrective exercise techniques is used to re-teach functional movement patterns by reestablishing neuromuscular control and promoting coordinated movement. Integration exercises help intermuscular coordination. Like the interstate highway, these exercises do cross state lines as they use multi-joint actions and multiple muscle synergies through total-body movements.

Integration exercises are functional in that they should be movements that are important to the client, such as things they encounter daily. These exercises should begin with slow and focused movements in a controlled setting to ensure the client can maintain optimal form and control.

However, over time and as the client improves, the movements should be progressed by changing resistance, speed, planes of motion, base of support, introducing upper body movements, and even adding impact in some cases.

An example of an integrated exercise for the client with knee valgus may be a ball-wall squat with a mini-band around the knees. The squat pattern is functional, and the mini band will encourage the client to maintain proper knee position during the movement. As the client improves, the mini band may be removed (thus removing the feedback), and weights may be added to increase the resistance.

This could eventually be progressed by squatting without the use of a ball and then to changing base of support by performing a split squat or lunge. The lunge may be progressed through the three cardinal planes of motion, and finally, a squat jump may be added to enhance the eccentric demand.

Focusing on the eccentric portion of all integration exercises and improving postural control in all planes of motion may help to reduce specific injuries. Like the activation phase, optimal form is vital during the integration exercises.

The goal of corrective exercises is to re-teach a better movement pattern. This is applied to all clients, not just those recovering from injury. Thus, it is vital to follow the process of identifying movement dysfunction, following the four-phase Corrective Exercise Continuum, and to execute that programme with optimal form and control.

Today more people have long work hours, use better automation and technology, have less time for recreation and move less on a daily basis. This new environment produces more inactive and nonfunctional people and leads to dysfunction and increased incidents of injury including low back pain, knee injuries and other musculoskeletal injuries.

People who go to gyms for better musculoskeletal and metabolic health need to realise that their training protocols should be geared to handle the challenges of the new environment. The only way to achieve this is to follow the integrated approach as detailed above with proper attention to increasing appropriate fitness, increasing strength and neuromuscular control and training in different planes of motion as well as different environments (stable and unstable).

Ranadeep Moitra is a strength and conditioning specialist and corrective exercise coach