What’s that metallic thing? Is it a statue? Is it a symbol of something? Despite being in a tearing hurry, my inquisitive self stopped me in my tracks on spotting a gigantic structure next to the town square. Elderly folk were settling down in any seating space they could spot around it. “That’s the Raging Bull. It will move at 12,” one of them told me.

That made little sense and I had to return to our conference venue before 12 anyway. So I hastened past the growing crowd to a larger extension of the square. My destination was a bank, which I was told was 10 minutes away. Britain would stop using paper £20 and £50 notes by end-September and I had some leftover from my last England visit. “Try changing them at a bank or a post office,” my UK friends had advised me.

As I wound down New Street, following Google Maps, the post office on the way was of no help. So the bank was my only chance. The official I met at the gate responded in the negative but asked me to try my luck at the counter. The girl there simply took my paper notes, counted them and handed me £20 Jane Austen notes in polymer, no questions asked! Never have I been happier to come across my favourite 19th century novelist!

I was then at peace to look around, as I made my way back to the conference venue.

Getting to be in a city when it is hosting a major international sporting event is always a different experience. And being in Birmingham in the first week of August, there was no way one could let go of a chance to be part of the Commonwealth Games (CWG) action. We were staying in Bromsgrove, about 20 minutes by car from Birmingham proper. And our hotel was a good 20-minute walk from the spot of commercial zone that the sleepy hamlet had. So it was not till we reached Birmingham that morning that I could get a feel of it all.

The souvenir megastore, apart from selling all kinds of games merchandise had an awesome cool-off zone with fountains and a reflective pool

New Street, which housed the city centre rail station, was bathed in CWG colours. And Perry, the Games mascot, was smiling back from shop windows and banners hanging from tops of buildings. A wave of pedestrians was surging towards what I had by now figured out to be Centenary Square. “Faster, mom, faster,” an eight-year-old prodded, dragging his mother along, worried that he would miss the Bull in action.

The Games promotional meet that I was attending was taking place at UK House, adjoining Centenary Square. Though I missed the Bull then, after lunch we were back at the Square to witness the spectacle which was taking place on the hour every hour.

At the stroke of 2pm, a cheer went up as the Bull raised its neck, moved its head sideways and snorted, emitting a puff of smoke. Then its front and hind legs propelled forward in a suggestion of motion. “That’s Perry’s Dad,” said a father to his young one. Perry, the bull mascot, is lean and friendly, unlike this mean, muscular bulk of aluminium that had starred at the Games inauguration and since then, placed outdoors, had become the city’s biggest tourist magnet. A campaign was on to find a permanent home for the Raging Bull somewhere in the city rather than scrap it after the Games.

The Square also housed the Games souvenir megastore. In front of it, a shallow reflective pool had children jumping about in front of sprinklers. In a country coming out of a heat wave, it was the best way to be when outdoors. The gift shop had ample choices, with one section dedicated to Team England accessories. As a testimony to Birmingham’s diverse population, India and Pakistan team shirts were selling as well.

The sales counter was offering discounts on tickets as gratification for bulk purchase. The main ticket office was across the road, on the ground floor of the Birmingham Library. There was a queue in there, though negligible by Indian standards. A man was trying to sell the next day’s India vs Australia T20 final ticket at the marked price. With India having knocked out England in the semi-finals, many local fans had lost interest. My gracious hosts, VisitBritain, had already picked up match tickets, so my attendance at the India vs Australia showdown was certain.

Edgbaston was where the women’s T20 cricket was held and even the beer glass was in the spirit of things

This 2022 edition was already in the record books as the most-attended CWG ever in the UK, having sold over 1.3 million tickets even before the start of the Games. “Local residents from West Midlands have picked up 500,000 of those,” a CWG organiser informed us at UK House.

“The city has come alive. In my five years of stay in Birmingham, I have never seen anything like this,” Neelabha Chatterjee, a Kolkata-born hotelier, told me over lunch at UK House. “My hotel is hosting a Kenyan CWG delegation. Wish I had more rooms,” he said.

Action time

On match day, we gathered at the hotel lobby to get our faces painted with India stripes. Zoey, a Bromsgrove local from our host team, had got poster colours. With Chak De! India blaring on a bluetooth speaker, our coach set off for Edgbaston in the afternoon.

We met lots of Indian fans along the way as we walked into the ground. Many of the English folk I spoke to also pledged support to India. “They are winning so much anyway,” said Shelley Croghen, an elderly lady from the city. Australia was indeed way ahead of other nations in the medals tally. “Why do you even ask? Those are Aussies!” grimaced Matthew Pateman from Luton. Some sporting rivalries run in the blood!

Two young women on stilts formed the welcoming party at Alexander Stadium, while pulsating bhangra held sway inside

Our tickets had access to the Tom Dollery lounge in the South stand, where I spotted ’70s England and Warwickshire star Dennis Amiss’s cricket gear on display. A dholak player and his ceremonial turban-clad bandmates were raising a bhangra beat every now and then. But after lunch, the match tilted the other way once the set batters, Harmanpreet Kaur and Jemimah Rodrigues, were dismissed, and though we cheered as best we could, it ended in disappointment. “We will do better tomorrow,” we consoled ourselves.

Go for gold

Indian players were featuring in five gold medal matches on the last day of the Games. By the time we reached the Birmingham College ground for the men’s hockey final, badminton stars P.V. Sindhu and Lakshya Sen had their golds in the bag. So we were quite upbeat. The sprawling campus, seemingly without a boundary wall, had markers everywhere to guide visitors as it was easy to get lost. The only seller we encountered was Gavin, a Welshman, who had flags of several countries on display on a table. “Sorry, no India flags. I had brought some but they sold out within 10 minutes. In fact, there was a queue at my table!” he exclaimed.

There was music blaring as we neared the ground. A small CWG souvenir shop stood at a side. Bio-toilets had been set up in a row outside the entrance. People posed for selfies with a Perry cutout. Unlike Edgbaston, the stadium itself was small and intimate. It had a huge electronic scoreboard that came as a surprise in a college ground. Obviously the venue had been majorly refurbished to host international matches.

The Australian players in yellow cut striking figures on the deep blue turf. Our men in blue were less prominent because of their shirt colour and, as the minutes ticked on, became even less visible as the ball hardly left the sticks of their opponents. The first goal came in the 12th minute, the second in the 18th. The yellow shirts were everywhere, be it in the field or the stands. “Aussie, Aussie, Aussie, oye, oye, oye,” was a battle cry the supporters chanted as their players raided our box again and again.

At half time, we were already 0-5 down. It was impossible to take the drubbing anymore and I walked out. Outside, a big group of Punjabi men had queued up at the beer stall. “There are 18 of us, from all across the UK and a couple even from India. The match may be over for us but we are having a grand reunion,” smiled Daljeet Singh from Glasgow.

There was little time to drown our sorrow — India lost 0-7 — as there was the closing ceremony to attend in a few hours.

Final hurrah

This was the first time that we were entering Alexander Stadium, which had hosted the athletics action. Brightly painted double decker public buses brought spectators from all across the city and deposited them at a point beyond which vehicular traffic was barred. Public transport was included within spectator tickets to reduce the carbon footprint. It was a breeze walking in with our water bottles (unlike at Eden Gardens, where everything is seen as a potential missile). In fact, the organisers were encouraging spectators to carry bottles and utilise the free water refill stations set up at all venues.

Two winged women on stilts formed a towering welcome party. What was equally eye-catching was the sight of supporters of various countries coming in their national jerseys. Our £260 seats were right in front at the ground level. I struck up conversation with a group in England colours. Among them was Susannah Townsend, a member of England’s gold medal-winning hockey team at the Rio Olympics in 2016 and the bronze-medal winning team for Tokyo 2020. She hung up her international boots only last November. A couple of players from the current squad later came up to the sidelines to greet her during the players’ march.

As for the ceremony itself, our high point surely was when a big Punjabi group in bright dhoti-kurta and ceremonial turban went up on stage, dancing balle balle. Some played the dhol as one of them sang a Punjabi song. It was a heartwarming gesture of inclusion — Punjabi culture is very much a part of Birmingham’s heritage. Local spectators seated nearby recorded us on their mobile phones as the men in our group went berserk dancing.

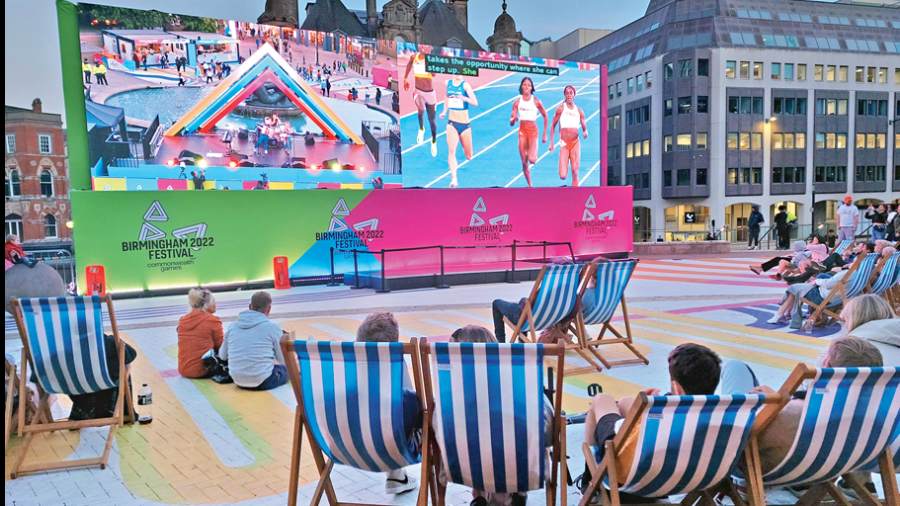

Victoria Square had a huge screen where one could watch the games

The next day, with the Games over, Victoria Square where a giant screen had been set up to screen live action all through the CWG, looked lifeless. But the volunteers were still on duty. Dressed in white and orange T-shirts, they were local residents of all ages who had pledged their time for the biggest sporting occasion in their city. They had been everywhere — the stadiums, the rail stations, the city centre, at important traffic crossings, at major tourist attractions and even outside Heathrow airport.

Aisha Haji was one of 300 such deployed outside Edgbaston at the T20 final. Daughter of Indian immigrants, she knew nothing of cricket but was soaking in the atmosphere as she directed spectators to the right gate. Penny Ashfield, a lady with silver locks, was stationed outside the hockey venue, seeking out children accompanying parents to gift them a Perry Activity Book. “We are called Games ambassadors,” Mandy Chapman, a 57-year-old finance manager standing at the crossing of New Street, said with a smile. Her duty partner for the afternoon was Dawn Barnaby, a 25-year-old data engineer with an auditing MNC. As Chapman spoke of how much fun they had been having, making new friends like Dawn or helping tourists, a child leaned towards her from his mother’s lap. “Oh, you want a high five with this?” exclaimed Chapman, whose right hand was inserted in a giant foam hand, with the index finger pointing outward. As the child got his wish and beamed, she quipped, laughing: “Who knew an oversized foam hand could give so much joy?”

These volunteers were happy to share their knowledge of the city, give directions and share tips with the Games visitors. This spirit of standing up to be counted when one’s city needs one’s services is what made this fleet of 14,000, aged 14 to 84 years, the real stars of the Birmingham CWG for me.

Pictures by the author

The volunteers were a cheery lot

Nuggets And Numbers

1: Birmingham 2022 was the first Commonwealth Games planned to leave a carbon-neutral legacy

4: The number of new sports at the Games — women’s T20 cricket, basketball 3x3, wheelchair basketball 3x3, para table tennis

136: The number of women’s medal events, making these Games the first multi-sport event to have more women’s than men’s medal events

1.5 million: The number of ticketed spectators

14,075: The number of volunteers

72: Number of Tiny Forests — the size of a tennis courts with 600 native trees — planted in the run-up to the Games, for each of the participating nations and territories