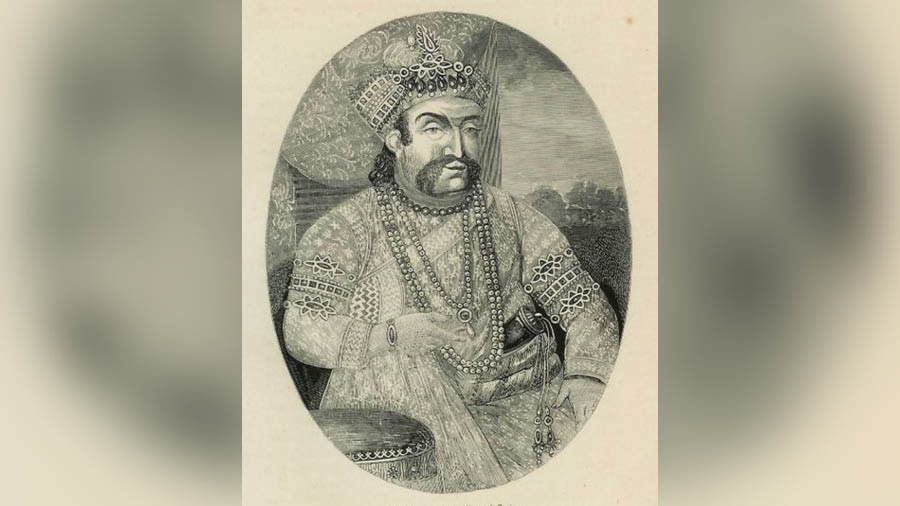

It is difficult to ascertain conclusively when and how kite-flying became a part of Calcutta’s culture. The most popular theory ascribes this to the man who brought biryani to these shores – Nawab Wajid Ali Shah of Lucknow. May 13, 1856 – the steamer McLeod berthed at Bichali Ghat in Metiabruz. As the nawab stepped off, little did he realise that he was going to spend the remaining three decades of his life here. But once that realisation dawned, Metiabruz would go on to literally become a little Lucknow, complete with every aspect of the royal life back home, albeit with less pretensions. Cock-fighting, shayari (poetry) reciting and kite-flying were now commonplace in the lanes of Metiabruz – thanks to a man who lost his fortune, and was now desperately tried to cling on to the memories.

A popular theory claims Nawab Wajid Ali Shah brought kite-flying to Bengali shores

But even if kite-flying predate the nawab in Calcutta, there’s no doubt that his arrival did bring a great boost to this form of sport-cum-entertainment in these lands. The nawab didn’t land alone in Calcutta – accompanying him were the royal retinue and several of his erstwhile subjects. Many of the latter were skilled in kite-making, and set up shop at Metiabruz. To this day, kites made in Metiabruz are supplied to various parts of the country – UP and Bihar being the biggest markets. By the end of the 19th century, the affluent Bengalis, popularly known as babus, of north Calcutta, became big patrons of the art of kite-flying. The legendary brother-duo Latu babu and Chhatu babu were famous for their kite-flying celebrations. They would allegedly tie currency notes to the tails of the kite – a practice that was also followed by several others like Pradyumna Mallick. The more prosperous the babu, the bigger the denomination of the note attached. The babus would involve in kata-kuti (aerial dogfighting) from the terrace of their houses. A big cheer would go up from the lackeys when their master would score a win.

The relatively low cost of participation meant that literally anyone could take part in a kite-flying contest

Yet, while it may have started with the aristocracy, kite-flying would not remain restricted to the blue bloods alone. It would spread across the length and breadth of the land as a favourite pastime of young people, in particular. The relatively low cost of participation meant that anyone could literally take part in a kite-flying contest. All that was needed was paper, wooden bamboo sticks (kanchi)and some adhesive to build a kite.

Even the high and mighty was not exempt from its enticement. A famous anecdote says that while walking through a bylane of north Calcutta, Swami Vivekananda spotted a young boy flying a kite on his terrace. Swamiji beckoned the boy to come down to the streets and joined him in flying the kite. Passersby were pleasantly shocked to see the famous monk passionately fighting to win the honors with the latai (spool) against other combatants, most of them kids. Manna Dey, the famous playback singer, may have left north Calcutta for Bombay, but he didn’t lose his love for kite flying. It is said that every Saturday afternoon, he used to indulge in kite flying fights with his neighbor – a certain Mohammad Rafi!

A kite shop in Kolkata

My childhood was spent in a rented accommodation where we didn’t have access to the terrace. My earliest memories of kite flying, thus, constitute mainly of the boys from a nearby slum, adjoining the Sealdah south train track, flying their colourful kites over the train tracks, at times quite dangerously. As I was strictly instructed not to go near the rail tracks, watching the kites fly away towards the Jadavpur University campus was the only pleasure I could have back then.

It was much later when we had moved to our own place and this time with a nice terrace that I got firsthand experience of this attractive pastime, thanks to an uncle who was quite an aficionado. The terms still roll off my tongue – a kite which was made from four different coloured papers was known as Chowringhee; Petkatti had a horizontal split around the middle of two different colored paper patches; Chandiyal had a moon-like emblem in the middle, while the one with a fancy tail was called Mayurpankhi, if memory serves me right. But the name I liked most was Mukhpora (literally ‘face-burnt’). Being never very good at the art though, my preferred part of the whole thing was the chase for the fallen kite – a group of boys running hither and thither, adrenaline pumping, like a pack of hounds searching for a shot-down bird. Instead of the boom of a bullet, what set off this chase was the phrase ghuri kata geche (the kite has been cut).

Workers make 'latai' (spools), in Kolkata

I really don’t know how kite-flying became associated with the festival of Vishwakarma Puja – a celebration that typically heralds the impending arrival of the mother goddess. At one time, the Bengali babus used to have kite-flying as part of the celebrations associated with Durga Puja. Given the adjacency in timings, it probably it spread to Vishwakarma Puja as well. But, in the middle of September, if you are not from Calcutta/Bengal and land up in these parts, be ready to be welcomed by a handsome mustachioed idol with kites adorning his personage in every corner of the city.

I grew up in a part of the city that was marked with several well-known medium to small industrial units. Sulekha Ink, Bengal Lamps electrical works and the big sprawling campus of Usha Motors – were all lined up on my daily school journey route. These places used to sport a festive look in this time of the year as the godly engineer was celebrated with gusto and colorful pieces of paper flooded the September skyline.

Today, Bengal Lamps and Sulekha only exist as bus-stand names, while the South City complex and mall have devoured Usha. The lord Vishwakarma is nowadays largely worshipped by the rickshaw pullers and garages in and around my place. Yet, when an occasional bho katta (a war cry – something akin to ‘gotcha!’) comes to the ear, the heart still fills up with nostalgia.